Water shortage exacerbated by leaks in creaking infrastructure, erratic power supply, shrinking reservoirs and lack of funds

LUSAKA, Sept 14 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - Dorothy Zulu's dream is to have a water tap and a small vegetable garden in her home in Ngombe, one of many slums in Zambia's capital Lusaka.

To get water Zulu, a mother of six, has to be at one of the dozens of water kiosks dotted round the dusty neighbourhood by 6 a.m.

"You have to wake up early because by 10 a.m. there is no water left," Zulu, 54, said while washing her laundry in the murky waters of a shallow stream running through Ngombe.

Zulu survives on 10 kwacha ($1) a day and, like the majority of Ngombe's 120,000 residents, spends up to a third of it on water.

"If you don't have money here you can't drink water," Zulu told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Overall, the proportion of people in Zambia with access to clean water has increased since 1990. But in urban areas it has dropped to 85 percent in 2012 from 89 percent in 1990.

With Zambia's population forecast to grow five-fold or more by 2100, experts expect the southern African country will struggle to meet the demand for water, especially in urban areas where population growth is expected to be fastest.

To achieve universal access to clean water and sanitation by 2030, one of the development targets global leaders are due to adopt at a U.N. summit later this month, Zambia will have to provide water to all, including those living in slums.

It will also need to focus on repairing and expanding its dilapidated infrastructure, water experts say.

"The lack of access to water in informal settlements is a global issue which reflects a broader pattern of discrimination and inequality in the world," Catarina de Albuquerque, executive chair of the global partnership organisation Sanitation and Water for All, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

"The underlying idea of the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals) is that no goal should be considered as met unless it is met for all economic and social groups, including the people in the slum."

Only about 36 percent of Lusaka's more than two million residents have piped water in their homes, according to Zambia's National Water Supply and Sanitation Council (NWASCO).

Only half of Ngombe's residents have access to clean water, according to Brian Chanda, plant superintendent at Ngombe Water Trust, a community group which manages the slum's water supply.

SLIDESHOW: When a child's playground is also their toilet

The rest rely on often contaminated shallow wells, private boreholes or vendors who sell water at a 50 percent markup from the tariff set by the Ngombe Water Trust.

The Trust has two boreholes in Ngombe and also buys water from provincial utility Lusaka Water and Sewerage Company (LWSC), but water from LWSC is rationed in parts of Lusaka because demand exceeds LWSC's supply, creating a shortfall of 80,000 cubic metres per day, according to UN HABITAT.

As a result, the Trust is only able to fill its tanks for four hours a day.

"We need more boreholes because the population is growing almost every day," Chanda told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

LWSC has promised to dig two more boreholes in Ngombe by October but 10 extra boreholes would be better, Chanda said.

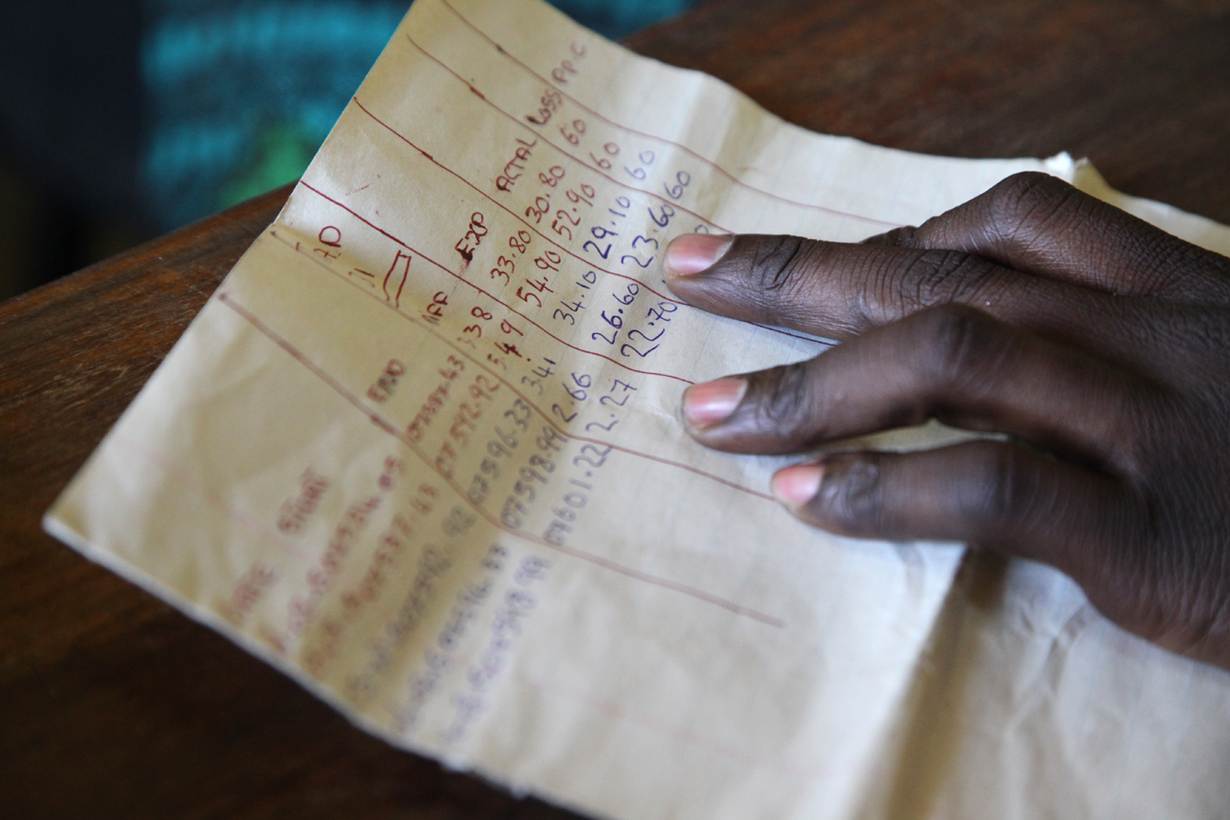

MONEY TALK

The rapid expansion of illegal settlements like Ngombe - which draws people from the farming heartlands, seeking better economic prospects - is challenging for municipalities trying to provide formal infrastructure like piped water.

In Lusaka, the problem is exacerbated by water lost through leaks due to creaking infrastructure, erratic power supply, and shrinking reservoirs and rivers during drier seasons.

Another problem is cash.

"Money is the biggest problem," Yvonne Mwandu Siyeni, a manager at LWSC, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

"If we have money available we've been hoping to extend service in those areas, except at the rate at which they are expanding we can't cope."

More income would be generated if the authorities could stop residents, desperate for a reliable supply of water, from drilling private boreholes instead of applying to be connected to the LWSC, experts say.

In 2014, LWSC lost 42 percent of its supply, well above the acceptable benchmark of 25 percent, mainly due to "huge" water losses through crumbling infrastructure, according to NWASCO.

"One of the reasons people are drilling boreholes is they're also looking at the current capacity of Lusaka Water to provide the service," Reuben Sipuma, programme manager with the charity Water and Sanitation for the Urban Poor (WSUP), told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

But for Sumila Gulyani, urban strategy expert at the World Bank, the failure to supply water to unplanned settlements is not just about money.

"If you're in London or Lusaka and you have a regular house or apartment there is no question that (a water utility) would deliver piped water service to you," Gulyani told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in a phone interview from Washington.

"But when it comes to serving the slum, everybody (says) 'Oh, we don't have the money to extend full piped service to the slum'."

Poor people are simply not a priority for water providers, according to Timeyin Uwejamomere, technical support manager of urban programmes at charity WaterAid, which built two water kiosks at Ngombe.

"This injustice continues against the poor all the time. The challenge is that we don't have the right leadership and mindset that is dedicated to delivering this," Uwejamomere told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

"These chaps who run these utilities have salaries that are subsidised and are paid for by the government. Whether they make a profit or not, they still get their salaries, so where's the incentive?"

Until an incentive is found, piped water will remain but a dream for Zulu.

"I would love to have a small vegetable garden if I had water in my home," she said as she finished rinsing clothes in the dirty stream. "I don't think Lusaka Water is taking good care of this community." ($1 = 9.94 kwacha)

(Reporting by Magdalena Mis; Editing by Katie Nguyen; Please credit Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers humanitarian news, women's rights, corruption and climate change. Visit www.trust.org)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.