We asked Salvadorans, including a gang leader, why their nation has turned so violent

By Anastasia Moloney

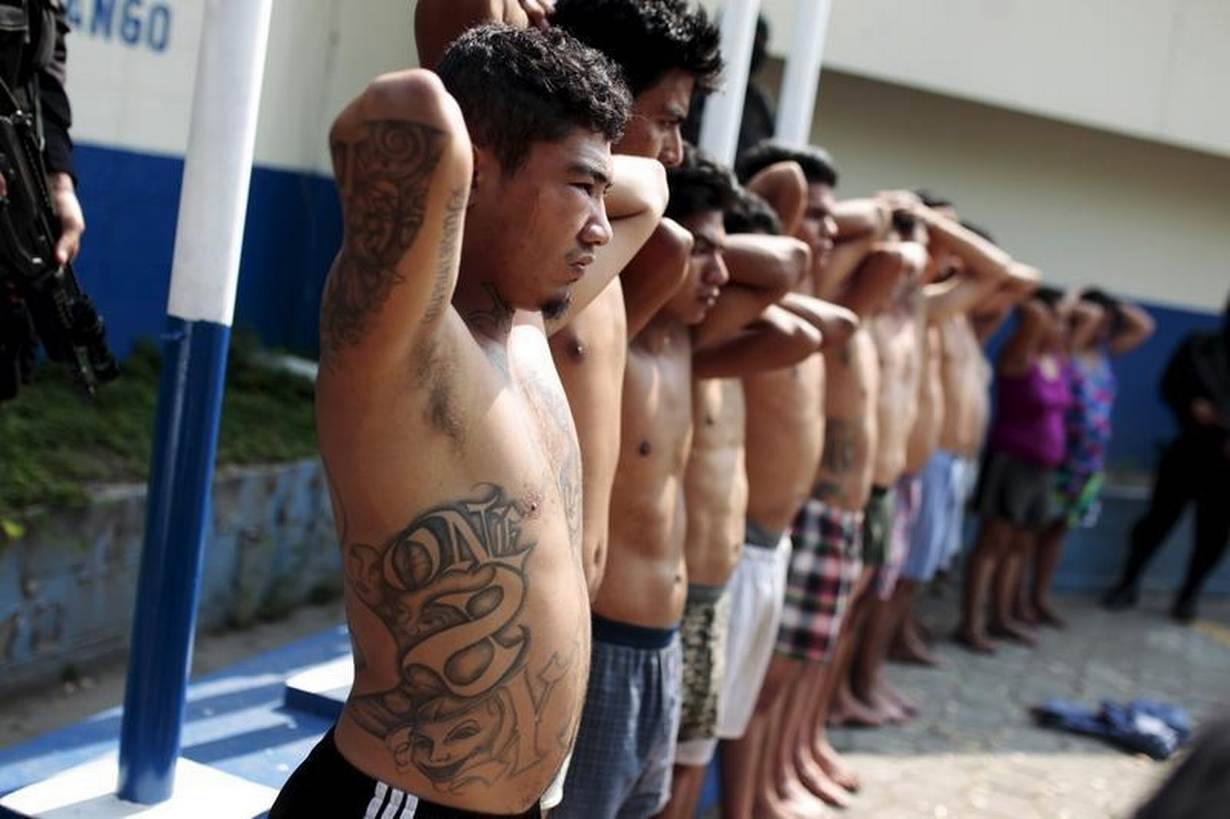

SAN SALVADOR, May 11 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - Gang violence has plagued El Salvador for decades, making the Central American country of 6.4 million people, one of the most dangerous outside a war zone.

More Salvadorans have been killed since the end of the country's 12-year civil war in 1992, than during the entire conflict which killed an estimated 75,000 people.

The violence has prompted much soul searching about the best way to tackle gang warfare.

The Thomson Reuters Foundation asked Salvadorans, including a teacher, university academic, gang leader and church leader: Why is El Salvador so violent?

Below is a selection of their views:

* SOCIETY DAMAGED BY BREAK UP OF FAMILIES

El Salvador's 1980-92 civil war, poverty and gang violence have driven around three million people to leave the country, most of them heading to the United States seeking a better life.

A generation of children was left behind to be cared for by relatives in the absence of their parents who emigrated.

"Family disintegration has a lot to do with the violence facing El Salvador today," said schoolteacher Joaquin Orellana.

Gang life starts with children coming into contact with gang members in and outside of school, he said. Before long, they are skipping school to hang out on street corners and run errands for gang members to earn pocket money.

"Relatives, often an aunt or grandmother, ... can't stop a young teenager from wanting to go out and being on the street. They don't have the control," Orellana said.

Many children are left home alone while their relatives work long hours, making them easy prey for gangs, he said.

* U.S. DEPORTATION OF GANG MEMBERS

El Salvador's most notorious gangs - Calle 18 and Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) - began life on the streets of Los Angeles.

They were set up in part by the children of Salvadorans who fled the war in the 1980s, to defend themselves against well-established Mexican and African-American gangs.

Under U.S. immigration policy, tens of thousands of gang members - including convicted criminals who had been in prison - were deported home in the mid-1990s where they spread the gang culture learnt in Los Angeles.

They arrived to a country in turmoil. Struggling to recover from war, El Salvador could barely cope with the influx.

"The violence today is a phenomenon fuelled by the actions of the U.S. government that saw mass deportations of mostly young men," former congressman Raul Mijango told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

"Many of those deported had been part of criminal groups. They knew how to organise themselves and they started to build roots in their communities," said Mijango, who helped negotiate a 2012 truce between gangs, which later collapsed.

* GANGS PROVIDE INCOME, IDENTITY

Up to one in 10 people in El Salvador is in some way involved with the gangs, known as maras, experts say.

Santiago, a high-ranking gang leader in Calle 18, says he joined the mara when he was 17.

"For those who don't have a family, gangs give them a family. For me, the gang gave me an identity. A way of life. Gangs fill a need in a young person," he said.

"My mother told me not to get involved with the gangs and I did exactly the opposite. Nobody made me to join. I just joined. I didn't think about it. I was told I'd defend my neighbourhood and go to parties. In our marginalised communities there are no jobs. Gangs are the only option."

* GANG VIOLENCE IGNORED FOR TOO LONG

Political analysts say the authorities failed to take gang violence seriously when gang-related killings began making headlines in the early 1990s.

"The state ... has been slow to react. In the past, gang violence wasn't seen as a problem the state had to deal with," said Rodrigo Bustos, El Salvador director for child rights group Plan International.

"Currently the government has the legitimacy, backed by society and all political parties, to go after the gangs with everything they have to recover territorial control and to send in the military."

* FAILURE OF HARDLINE APPROACH

Right-wing governments in the early 2000s responded to gang violence with a 'mano dura' or iron-fist policy, sending army troops to bolster police efforts to fight crime.

Today, more than 15,500 gang members are locked up in El Salvador's overcrowded prisons.

Medardo Gomez, a bishop in the Salvadoran Lutheran Church and Nobel Peace Prize nominee, says this approach has done little to address the root causes of violence.

"If the police kill gang members, gangs also seek to get stronger. Violence generates violence," Gomez said.

"The gangs have grown to be so big that you can't stop them by putting them in prison or by killing them. However, that's what many people today think should happen."

He said gangs were from the most excluded and marginalised parts of society: "You can't just see the gangs as criminal groups but as a social problem that needs a social approach."

* U.S. WAR ON DRUGS

When the U.S. government pumped billions of dollars into Colombia in the 1990s to combat the country's drug cartels and stem the supply of Colombian cocaine to the United States, the problem shifted to Mexico, experts say.

In response, Mexico intensified its crackdown on the drug trade in 2006, prompting drug traffickers to move their transit routes to parts of Central America.

The incursion of Mexican drug cartels into parts of Central America, in particular El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala, helped the maras expand their reach and power.

"Mexican cartels saw ideal conditions in El Salvador and other parts of Central America, weak governance and impunity in which to operate in. They tapped into the gangs and they use them as local operators," said Jeannette Aguilar, head of the University Institute of Public Opinion in San Salvador.

(Reporting by Anastasia Moloney, Editing by Katie Nguyen.; Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers humanitarian news, women's rights, trafficking, corruption and climate change. Visit http://news.trust.org)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.