* Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Malnutrition is not destiny, it can be prevented through strong political actions and choices

We both come from very different backgrounds and have very different roles and responsibilities. It is the challenge of ending malnutrition–and the hope that it can be done--that brings us together.

The First Lady’s perspective: Hon. Mrs Roman Tesfaye

As First Lady of Ethiopia, my first engagement in nutrition came during the launch of the 2013-2015 National Nutrition Programme. During this time the Cost of Hunger Study for Ethiopia was released. As an economist, the bottom line of that study was shocking: 16.5 percent of my country’s gross domestic product (GDP) was being lost each year to malnutrition. I did not find this acceptable by any standard. Furthermore, if investments were made and we were to reduce stunting to 10 percent, we would yield total savings of US$12.5 billion through 2025. The Global Nutrition Report also indicates that for every dollar invested in nutrition, the return is US$16 – this, in economic terms, is a huge gain! Hence, making nutrition a policy priority is not only a response to the fundamental rights of our people for better health and nutrition; but it is also the cornerstone of our sustainable development.

As a mother of three grown up daughters, I know how it feels to see a child who is sick and not being able to do your utmost to help him or her. I remember all the sleepless nights worrying that my children were not eating, growing and thriving well. Now think of all the mothers out there – especially those without education and information –who feel helpless because they cannot help their children. Knowing that so many of these mothers’ worries and anxieties could be avoided through better nutrition, I feel the burden of the enormous challenges we need to tackle urgently.

As an ordinary citizen – I feel very saddened by the fact that in my country, so many young lives are either lost or disabled due to malnutrition –for a variety of reasons, including lack of knowledge, cultural and traditional beliefs, poor agricultural practices, and lack of access to water and sanitation services. Therefore, putting nutrition at the forefront of our policy and investment priorities is the only option for us. In addition to utilising Ethiopia’s agricultural potential, we need to promote modern nutrition practices and work closely with local communities so that we can meet our national nutrition goals.

The economist’s perspective: Lawrence Haddad

As an economist and champion of efforts to end malnutrition, I spend a lot of time trying to convince public financiers to ramp up their investments in high-impact nutrition programmes and policies.

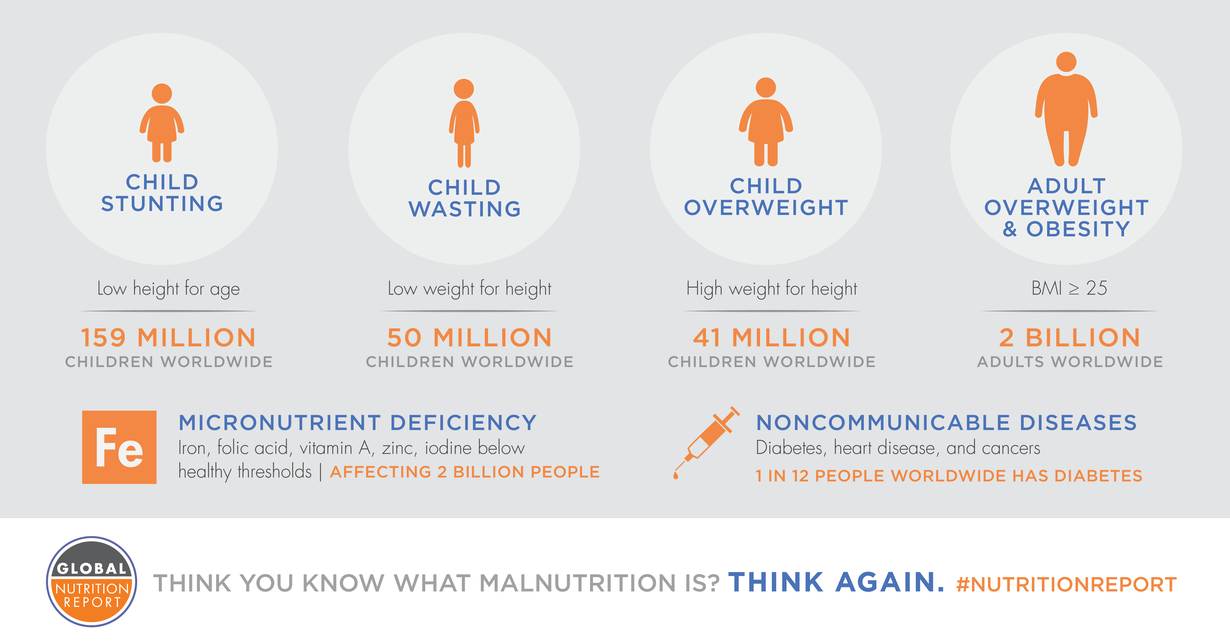

There are three very important reasons why malnutrition demands public investment. First, parents, communities and governments frequently don’t know they are experiencing or are at risk from malnourishment because all but its most acute forms are invisible. Second, there are no market mechanisms to help families deal with malnutrition in the first 1000 days: show me the bank that will lend parents enough money to take care of their baby for the first two years of its life on the promise that it will pay them back when the child is earning more money in the labour market as an adult. Finally, the costs to unborn children of failures to invest in the nutrition of mothers and mums-to-be are severe and represent large externalities generated by malnutrition.

But is it as a father that the subject really hits home at an emotional level. Fifteen years ago my wife and I adopted our beautiful children from Cambodia, both of whom were under the age of two. Their nutrition charts showed they had experienced significant malnutrition. Being able to see them grow strong under our care made me realise three things: first, children respond quickly to food, care and love; second, they cannot thrive on love alone; and third, if you have the means to help a child, you have the responsibility to do so—however that is expressed.

The 2016 Global Nutrition Report, launched today, shows that the world as a whole is off course to meet global nutrition targets, but, as it also shows, there is still hope. Many countries are on track to meet targets and many are on the verge of doing so. There are many success stories around the world, and more and more governments, donors and leaders --at all levels-- are stepping up for nutrition.

Ethiopia as a model of success

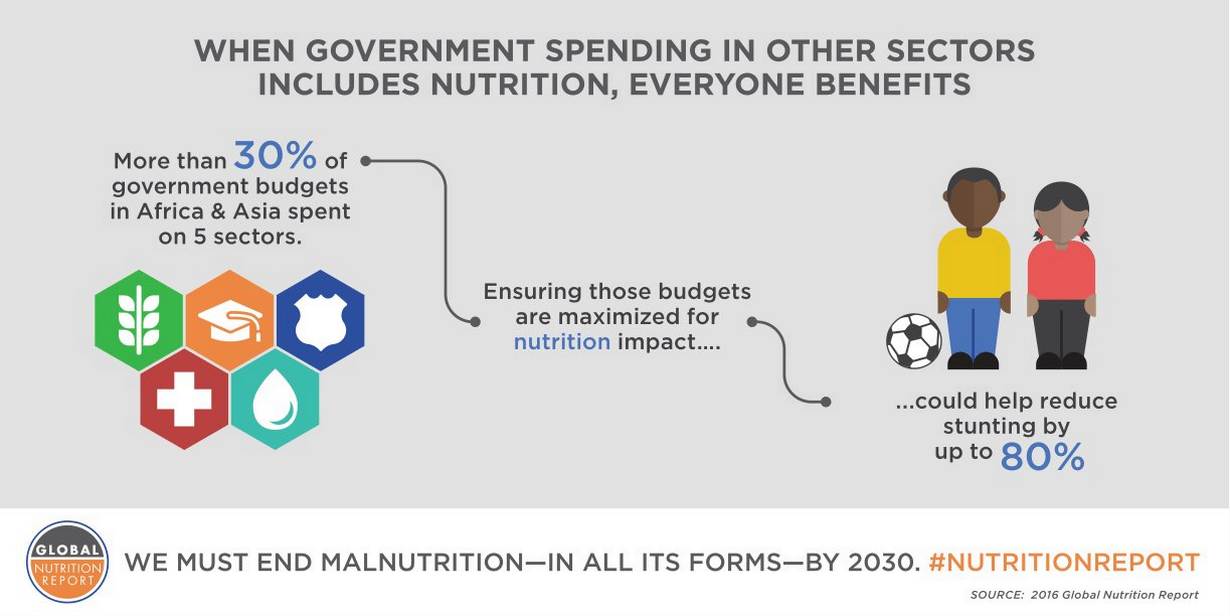

Ethiopia is one of the leaders in taking up the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) challenge of ending malnutrition by 2030. The country has come far in terms of addressing the health and nutritional needs of its population, although it still has a lot to do. Recognising the need to ramp up the intensity of our efforts, Ethiopia has developed new strategic approaches by designing a nutrition-sensitive agriculture strategy, a national school feeding program, and a nutrition-sensitive productive safety net program.

Mid-last year, the Government of Ethiopia re-affirmed its commitment by launching the Seqota Declaration – a commitment to end child under-nutrition in Ethiopia by 2030. This is a specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time bound (SMART) commitment—not a fuzzy promise that is designed to be easy to break. The Seqota Declaration Implementation Plan will focus on delivering high-impact nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions across multiple sectors including health, agriculture, water, education and social protection while creating an environment that supports these actions.

We believe that the Seqota Declaration will give Ethiopia more energy, strength and an additional platform for advocacy and social mobilization efforts to bring every Ethiopian around one shared goal – an end to stunting in Ethiopian children under the age of two by 2030. We also believe this declaration will inspire others around the world to make equally ambitious and SMART commitments.

The way forward globally

In short, we know what the costs of malnutrition are and we know how large the benefits would be from acting to end it. So to make sure governments and donors intensify their investments, all of us need to hold powerful stakeholders to account. The Global Nutrition Report aims to be a tool to help people all over the world to do this more effectively.

To end malnutrition by 2030 we need to form global, national and regional alliances across a wide range of stakeholders: politicians, parliamentarians, community and religious leaders, the media, civil society organisations, mothers, fathers and families.

No one can achieve this goal working on their own. But working together—at work and in the home--anything is possible. Malnutrition is not destiny, it can be prevented through strong political actions and choices. Join us and choose to end it—soon.

Roman Tesfaye is the First Lady of Ethiopia and Lawrence Haddad is a British economist and senior research fellow at International Food Policy Research Institute