Native Americans have the lowest employment rate of any U.S. racial or ethnic group, according to government statistics

By Ellen Wulfhorst

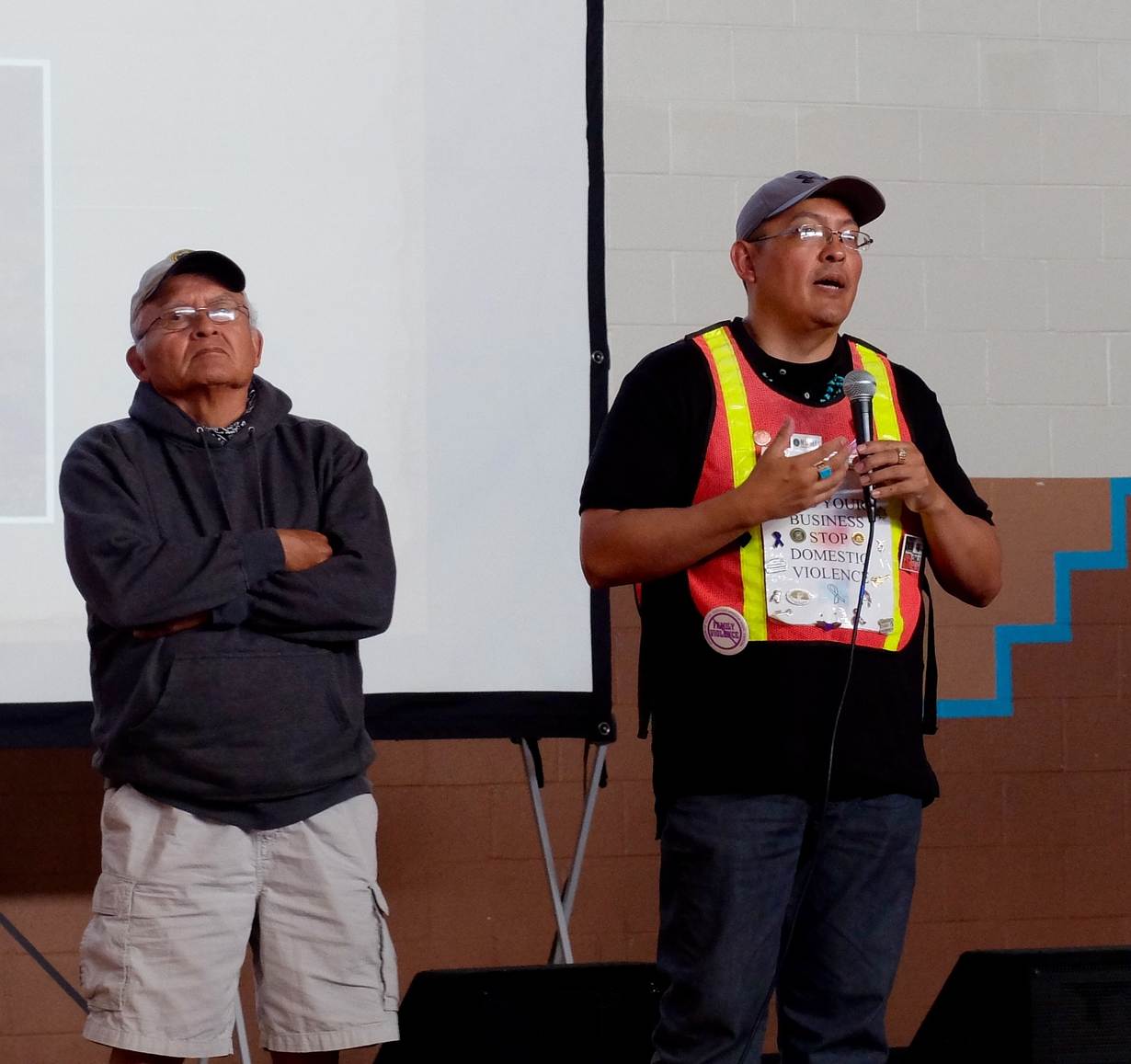

TAOS PUEBLO, New Mexico, June 24 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - J ohn Tsosie stood up before a small audience at a Pueblo Native American reservation and told the gathering how he hit the mother of his children.

Joining him was his father Ernest Tsosie Jr., who recounted how he too inflicted raging violence on his family.

"I did that, and as a result my sons followed in my footsteps and did the same thing," he said.

The father-and-son duo of Navajo Indians now travels the American Southwest, sharing their stories of violence and recovery to help troubled Native American men prone to alcoholism, drugs and domestic abuse.

"When I went to counseling, there was nothing for men. Every pamphlet they gave me was 'she' and 'her,'" the younger Tsosie told the Thomson Reuters Foundation ahead of a talk he gave this month at the Taos Pueblo reservation in New Mexico.

Father and son founded Walking the Healing Path, based in Window Rock, Arizona, headquarters of the Navajo Nation.

The pair set off on what would be a series of long walks, the first in 2004, to promote awareness of sexual violence and domestic abuse among Native Americans.

One walk took them more than 300 miles to Phoenix from Window Rock, and another coursed 700 miles around the Navajo Nation, the largest Indian territory in the United States.

They make public appearances to talk about domestic and sexual violence and alcohol abuse, which are deeply entrenched problems among Native Americans.

American Indian women are two-and-a-half times more likely to be sexually assaulted than women of all other races, and one in three reports having been raped, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

They are battered at a rate four times that of white women, according to the Justice Department.

Alcohol is involved in one in ten Native American deaths, more than twice the rate in the general U.S. public, and chronic liver disease and cirrhosis are among the leading Indian causes of death, according to government statistics.

Poverty plays its role, said John Tsosie.

Native Americans have the lowest employment rate of any U.S. racial or ethnic group, according to government statistics. The poverty rate for Indian families on reservations is four times the national family average.

"The man is the one who is the provider, who takes care of the family, so when you're at that poverty level, you can't even do that," John Tsosie said. "You begin to get frustrated, and domestic violence happens."

Added to that, Native American communities are far short of funds needed for shelters and social services, he said.

John Tsosie and his father told their stories to residents of the Taos Pueblo reservation, home to ancient adobe dwellings dating back to the 13th and 14th centuries.

Considered the oldest continuously inhabited community in the United States, it is a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The elder Tsosie, 74, said his story began one Sunday morning in the mid-1980s.

"After one of my all-night drinking things, when I got home, my whole family was gone," he said.

He watched his two sons struggle with the same demons and knew the cycle had to be broken, he said. All three men recovered with prayer and counseling, he said.

"They have forgiven me for what I did to them," he said.

His 41-year-old son calls himself a former victim and former abuser who sees how deeply domestic violence can be ingrained over generations.

"I've heard from victims, I've heard from perpetrators and a lot of them don't realize that it's wrong. A lot of them think ... to be abused is normal," he said.

"I saw my dad beat on my mother," he said. "I thought that's just how I was supposed to treat a woman as a man."

Many men on the reservation seem to have lost their self-esteem, said Jody Coffman, a home visitor with Tiwa Babies, a program for families at Taos Pueblo, where just over 1,000 Indians live.

"It's our women that are going off to college, that are becoming educated, that are marrying outside the pueblo," she said.

"The men kind of lost their way here and because sometimes they may feel trapped or stuck, they fall into those habits of drugs and alcohol."

Listening to the Tsosies from the audience, Larry Hinojos, a sexual violence prevention counselor in the New Mexico city of Albuquerque, said their message resounded because it was Indians speaking to Indians, about experiences they understood.

A lot of programs talk down to people, he said.

"I really like that their program is on the level of the community," Hinojos said. "It's really difficult to do what they do, and they do it really well."

(Reporting by Ellen Wulfhorst, Editing by Ros Russell; Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers humanitarian news, women's rights, trafficking, property rights and climate change. Visit http://news.trust.org)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.