"Using a toilet in informal settlements is one of the most dangerous activities for residents and women and the children have the biggest problems"

By Paola Totaro. Drone photography by Johnny Miller.

CAPE TOWN, Oct 12 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - Siphesihle Mbango was just six years old when her friend, Asenathi, begged her to go with her to the toilet then ran outside alone - and was never seen again.

Now 12, Mbango tells the story with an intense, unflinching gaze but her hands, fidgeting nervously as she speaks, show the trauma is still raw.

"We were at the crèche and she wanted me to go with her," but I told her I was busy, I was playing, I didn't want to go and she went out by herself," she said, at her home in a Cape Town slum.

"It was a long time she was away and when the teachers asked me, I told them she went to the toilet. They looked and looked for her for a long, long time. But then we lost hope. We never saw her again."

WATCH: Siphesihle Mbango explains what happened the day her friend disappeared forever

Mbango shares a one-room shack with her grandmother and two younger siblings in Endlovisi, a vast sprawl of more than 6,600 corrugated iron shacks perched precariously over the sand dunes on the southeastern edge of the South African city.

Part of Khayelitsha, one of the world's five biggest slums, Endlovini is home to an estimated 20,000 people who share just 380 or so communal toilets.

However, the family live in an area where there are no easily accessible toilets at all - and according to the community, residents have literally been dying for a pee.

"Using a toilet in informal settlements is one of the most dangerous activities for residents and women and the children have the biggest problems," said Axolile Notywala, of the Social Justice Coalition (SJO), a campaign group fighting for better sanitation in Cape Town's informal settlements.

"Many have to share inadequate temporary toilets like porta potties or chemical toilets and have to walk a long way without light. Others have no access at all and have to use fields or bushes. Children cannot go alone but finding a parent or neighbour is not always possible for them," he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Endlovisi made national headlines in 2012 when a local man was convicted of multiple counts of child rape and one count of murder between April 2010 and September 2011. The Western Cape High Court heard he had lured his victims to the bushes around the settlement before attacking them.

The same court will this month begin a pre-trial hearing of the case against two cousins accused of the murder of Sinoxolo Mafevuka, a Khayelitsha teenager who was found strangled in a communal toilet near her home.

Her brutal death sparked a renewed campaign by residents led by the SJC to highlight the link lack of sanitation, poor policing and crime in Cape Town's slums.

'NEW HOME'

The townships of Khayelitsha stretch for miles, a sea of ramshackle wood and iron shacks that confront visitors coming from the airport, but are out of view of the city's glass towers or the leafy suburbs built on the surrounding hills.

"The differences between the beauty of the city itself and what you see on the Cape flats is the starkest you will ever see in the world." said Jean Comaroff, a Harvard professor of anthropology and African Studies.

According to the 2011 Census, the townships are home to nearly 400,000 residents, 99 percent of them black.

Activists, however, believe that the population is at least three times bigger and according to a 2012 inquiry into policing in the township, 12,000 households had no access to toilets.

Meaning 'new home', Khayelitsha was established in the mid 1980s during the apartheid era as a vast dormitory for the thousands of workers who moved to Cape Town in search of jobs. When restrictions on the movement of blacks were lifted with the end of apartheid in 1994, hundreds of thousands more Xhosa people from the Eastern Cape poured into the city.

Endlovini was born a few years later, in 1997, taking over a swathe of unoccupied hillside land that had been both a nature reserve and public landfill. The community's refusal to be evicted gave the place its name: in the Xhosa language it means both elephant and fierce strength and is officially known as Monwabisi Park.

Nearly 20 years on, Endlovisi is a mix of desperate poverty and defiant resilience. Many shacks are now bounded by hedges, carefully tended not only to mark property boundaries but to shield shacks from Cape Town's notorious winds.

Other residents have installed the occasional pane of glass salvaged from demolition sites or doors secured with big, shiny padlocks. Tangles of electrical wires swing in the coastal squalls, communal water taps are a hive of washing activity and some shacks even boast satellite TV dishes.

On one sandy path, a small shop sells sweets to children as well as staples such as milk, bread and potatoes. Around the corner, a large, well-tended football pitch plays host to teenage boys in the late afternoon sun.

When the Thomson Reuters Foundation visited in September, a phalanx of men in high visibility overalls were hanging the settlement's first four street lights as the finishing touches were added to the first paved pathway through the settlement.

SLUMS ARE HERE TO STAY

Endlovini's curious semi-permanence, and the emergence of a growing middle class in some parts of Khayelitsha, is emblematic of the challenges posed by informal settlements to governments and city authorities in developing nations worldwide.

According to the United Nations, the urban population has grown rapidly from 746 million in 1950 to nearly four billion today. By 2050 another 2.5 billion will have moved to cities.

With 90 percent of this growth predicted to unfold in Asian and African cities, the U.N. warns that managing cities and population growth has become one of the most important challenges of the 21st century.

In Cape Town, cash strapped city authorities are not only finding it difficult to keep up with the land and housing needs of a burgeoning population but still face the huge task of trying to reverse the apartheid era engineering that built the spatial segregations that still exist today.

Khayelitsha's residents' push for better sanitation and security, led by the SJC, has been built on tiny steps - from numbering existing toilets to identify them to the creation of services to clean and maintain them. Padlocks were issued to encourage a sense of ownership of existing toilets but new facilities are desperately needed.

"The city's budget for water and sanitation has decreased again this year...21 per cent of Cape Town's households are informal but they only get one percent of the city's total capital allocation for water and sanitation," the SJO's Notywala said.

"The city still relies on offering undignified, inferior, temporary toilets meant for emergencies as long term solutions."

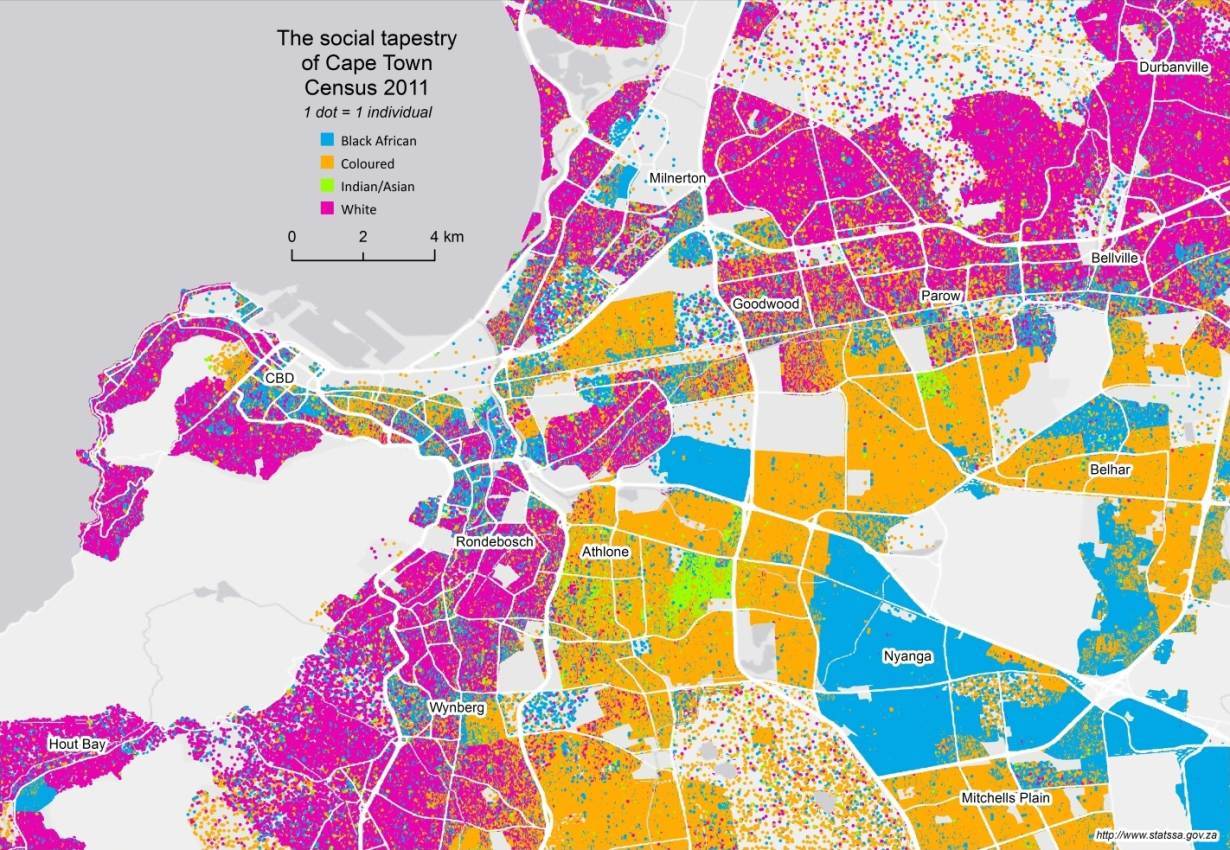

MAP: Modern day racial divisions in housing in South Africa, mapped by Stats SA from 2011 census data.

Ernest Sonnenberg, the City's Mayoral Committee Member for Utility Services said since 2006, the number of toilets per resident has gone up from one in 10 to more than one in four.

He agreed full flush toilets were preferable but argued that temporary toilets were a necessity as the alternative would be "no sanitation at all".

However according to research conducted by Yale University in Khayelitsha last year, improving access to toilets can also save money for cash-strapped municipalities.

The researchers developed a mathematical model linking the risk of sexual assault to the number of toilets and the amount of time a woman must spend walking there.

The model found that between 2003 and 2012, an average of 635 sexual assaults on women traveling to and from the estimated 5,600 toilets in Khayelitsha were reported each year. This resulted in costs to society - from medical expenses to lost earnings and legal costs - of $40 million each year.

The researchers found that doubling the number of toilets would lower costs to $35 million and reduce sexual assaults by 30 per cent.

"Higher toilet installation and maintenance costs would be more than offset by lower sexual assault costs," Gregg Gonsalves, lead researcher, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Inside a neat shack on the main road of Endlovisi, Phumzile Mbhovane, a 30-year-old father of four, sat in the semi darkness with his wife, Nobubele. He became blind suddenly in May last year, and now cannot work, let alone negotiate the paths downhill to the nearest toilets.

"It is another great sadness: my wife and children have to empty my toilet bucket. That is not their job," he said.

"But I do not have a choice."

MORE: This is the third story from SLUMSCAPES: a five-part series from PLACE. Using exclusive drone photography, interviews, and reportage, we uncover how residents of the world’s five biggest informal settlements are shaping their futures.

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.