For many women uprooted by Boko Haram, it is the first time they have visited a health facility, or heard about birth control

By Kieran Guilbert

MAIDUGURI, Nigeria, Jan 25 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - N estled among dozens of pregnant women huddled together on benches in the clinic's antenatal ward, their children clad in jumpers, jackets and woolly hats against the morning chill, Fatima Abdulai is glad to have the company.

Having fled her home in northeast Nigeria when Boko Haram militants struck in 2015, Abdulai is preparing for the birth of her eighth child - her first since arriving in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno state. But this time, she won't be alone.

"I gave birth to the others on the floor at home, alone," she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation at the Maimusari health centre in Borno, the heart of Boko Haram's seven-year-long campaign to carve out an Islamic caliphate in the northeast.

"There was no hospital in my village, so I had no choice," said Abdulai, who now lives in a rented apartment, rather than a camp for the displaced. "But some women in Maiduguri told me to come here ... now I know the risks of having a baby at home."

In Nigeria, where many women deliver without medical care, around one in 125 die during or just after childbirth, making it the world's fourth most dangerous country in which to give birth, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Many women in the northeast do not have a health facility nearby, cannot afford the transport or healthcare costs, or are compelled to deliver at home by their husbands and families.

But the destruction wrought by Boko Haram in the northeast, which has uprooted more than two million people, may eventually improve the sexual and reproductive health of countless women across the region, health workers and experts say.

Some 1.4 million of the displaced are now residing in camps and communities in Borno state, where aid agencies are offering free health services in camp clinics and state health centres.

For many women uprooted by Boko Haram, like Abdulai, this is the first time they have set foot in a health facility, or heard about antenatal care, birth control and family planning.

"We can challenge the norm of giving birth at home ... and have more conversations about women's health," said John Agbor, Nigeria chief of health for the U.N. children's agency (UNICEF).

FAMILY PLANNING FEARS

Many of the women arriving at health centres for the first time are fearful that using contraception may leave them permanently infertile, betray their Muslim faith, or spark a violent reaction from their husbands, several midwives said.

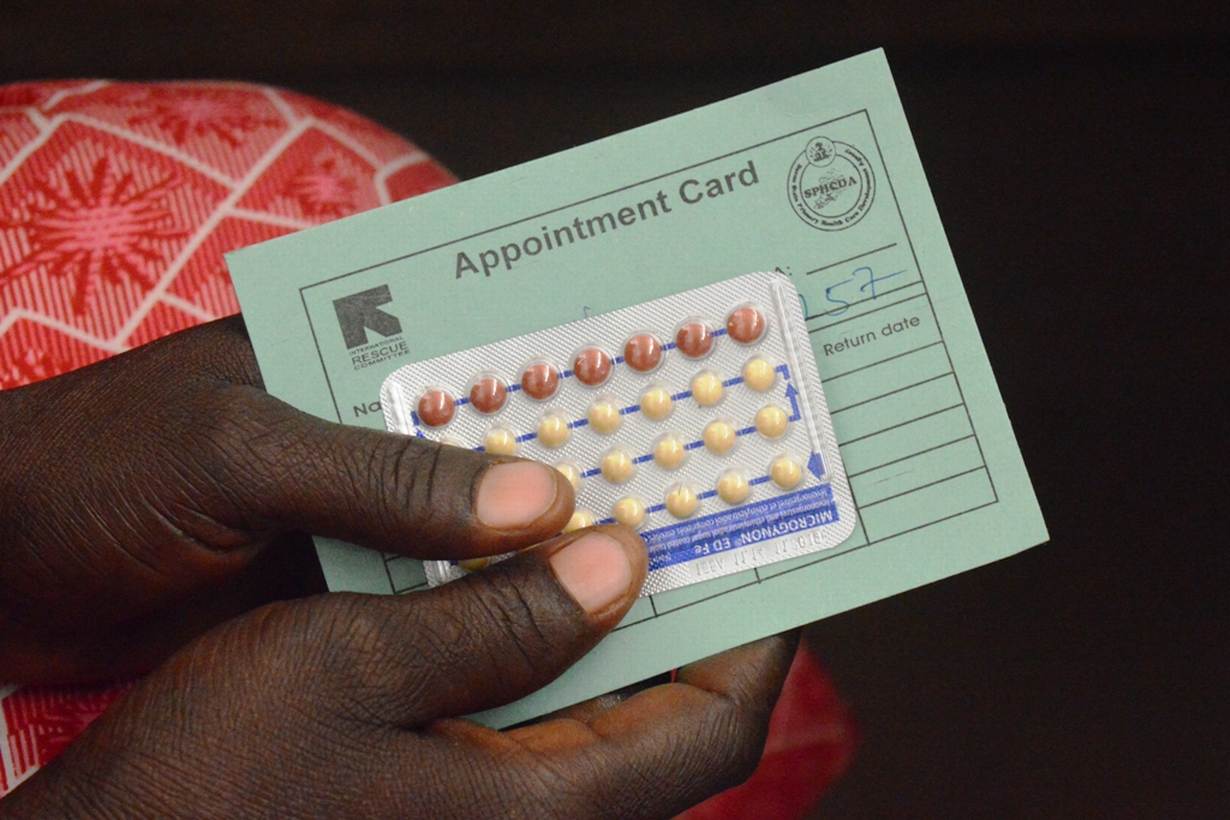

"Concerned about a cultural and religious backlash, we chose to raise awareness about the services by using local volunteers in camps and host communities," said Shehu Dasigit, reproductive health manager at the International Rescue Committee (IRC).

Yet the fact that more than two-thirds of the displaced in Borno live among communities rather than in camps makes it harder to reach and encourage women to seek health services, Dasigit said.

However, in health centres and camp clinics across Maiduguri, dozens of women queued patiently in the heat, saying that they would happily wait three or four hours to be seen.

While some of the women in Bakassi camp had decided to come without telling their husbands, 25-year-old Zuwaira Ali could not stop smiling as she attended her latest antenatal check-up.

"My husband knows my check-up schedule, and even reminds me when I have my next visit," said Ali, who had not been able to afford antenatal care for her first four pregnancies in Gwoza, the first town Boko Haram fighters claimed control of in 2014.

Many like Ali are considering family planning for the first time in a country where only around one in 20 married women use contraception, according to the Population Reference Bureau.

"Being displaced and living in a camp is not the perfect situation for children," said Ali, who is due next month.

"After this child is born, we will use family planning to wait before having any more," she added, sitting next to a pinboard covered with condoms, contraceptive pills and posters.

TAKING ON TRADITION

Not all women have such understanding husbands and families, according to Clara Afolyana, a nurse who works in Bakassi camp.

Men in the camps are often against birth control because they believe having many children will lead to more humanitarian aid, or prosperity in the future, several health workers said.

"Some men divorce, beat and even rape their wives if they merely bring up the idea of family planning," said Afolyana, who provides victims of such violence with counselling, anti-HIV medication and emergency contraceptive pills.

With many of the displaced contemplating a return home soon as Nigeria's army secures areas previously held by Boko Haram, several women said they hoped to challenge traditional beliefs about reproductive health in their home communities.

"The influence of grandmothers - who themselves gave birth at home and often every year - is strong across the northeast," said Fatima Kolo Lawan, a 23-year-old midwife at Maimusari who provides antenatal care to up to 100 pregnant women each day.

"We want those women giving birth now, the next generation of grandmothers, to deliver a different message to their daughters," she said, beckoning yet another woman into her room.

The state government is repairing some 500 health centres damaged or destroyed by Boko Haram, two-thirds of facilities in Borno, and aims to offer maternal and child health services in all of them, said Muhammad Ghuluze, director of emergency medical response in the state health ministry.

While such an approach would benefit women like Abdulai, she laughs heartily at the prospect of having a ninth child.

"For now, I'm just happy to be having this baby at a health centre," she said. "It feels good to be here."

(Reporting By Kieran Guilbert, Editing by Ros Russell; Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers humanitarian news, women's rights, trafficking, property rights, climate change and resilience. Visit http://news.trust.org)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.