Queer Tours is a reaction to the mass closure of gay bars, community centres and charities catering to the specific needs of the group, from HIV education to mental health

By Anna Pujol-Mazzini

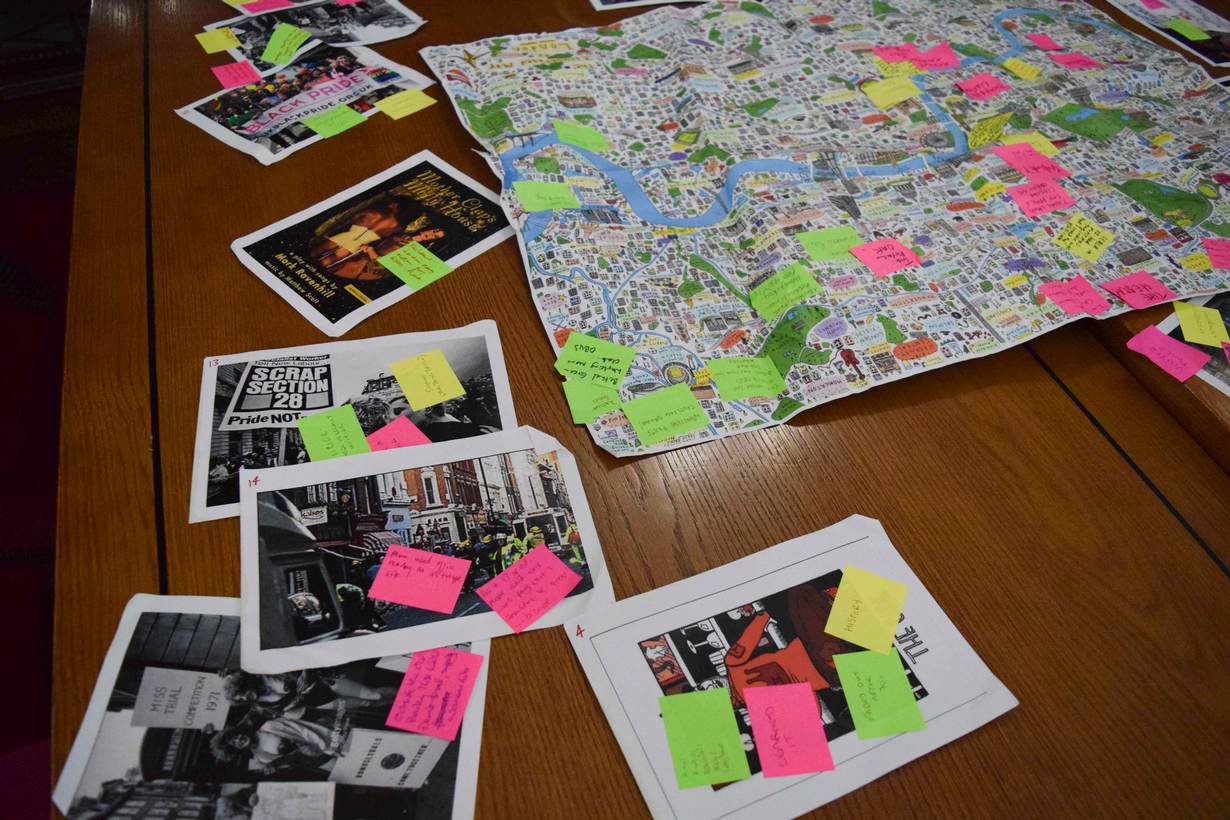

LONDON, March 21 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - In the red-carpeted north London town hall where one of the first gay weddings in Britain took place, activists buzz around a map of the city, armed with post-it notes.

Each participant is writing down personal stories as a member of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community in the British capital, in an attempt to write a chapter of history they say has been ignored.

"Anything which is seemingly small, or personal, it adds to the bigger picture" said Dan Glass, an LGBT rights activist who set up Queer Tours of London, the city's first LGBT tours.

"Every street has a queer story. You just got to dig for it" he added.

Queer Tours of London was set up last year as a series of walks aimed at sharing the complex history of LGBT activism in the city, to mark 50 years since the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in Britain in 1967.

On a recent afternoon, Glass led a tour of a dozen people from London's Trafalgar Square to sites in Soho, the capital's historic gay district, where campaigners led the fight against homosexuality being classed as a disease.

The tours each focus on a different issue affecting the LGBT community such as health concerns - from HIV to transgender sex changes - or the specific challenges LGBT asylum seekers face when fleeing persecution.

Queer Tours was formed as a reaction to the mass closure of gay bars, community centres and charities catering to the specific needs of the group, from HIV education to mental health, according to its website.

"We are using the history to protect our present," Glass said, adding that the profits from a recent string of sold-out tours will be distributed to projects supporting the community, including transgender prisoners and LGBT migrants.

Remembering LGBT history is important because "it's not taught generally, it's not covered in general books," said Jim MacSweeney, manager of gay and lesbian bookshop, Gay's the Word, which stocks a section on LGBT history.

"All you're taught in school is kings and queens and empires," he added.

Back at the town hall, many of the personal stories shared highlight broader themes for the LGBT community: the closure of venues where they used to gather and mental health issues and homelessness faced by their peers.

CLOSURE OF LGBT SPACES

Many of the gay bars and venues they remember as a part of their youth, such as the iconic Black Cap pub in north London or the Joiners Arms to the east, have now closed down as part of plans to redevelop them.

According to the Queer Spaces Network, a charity campaigning against the closures, between a quarter and a third of LGBT nightlife venues have closed down in recent years.

But activists say the closures have also affected services supporting the gay, lesbian and transgender communities.

"That's not just bars and clubs and cabaret spaces, that's LGBT mental health services, HIV services, domestic violence services," Glass told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

For many LGBT people who are not out or are not supported by families, dedicated venues can provide a safe haven.

LGBT spaces are vital so that people "can feel safer and more relaxed, can create and enjoy our kinds of culture, and celebrate our distinctive histories," said Ben Walters, a coordinator at the Queer Spaces Network.

Community venues also provide a supportive environment where people can seek help. Once they close, the most vulnerable people are left alone, activists say.

NOT FINE

LGBT people are more likely to experience mental health issues than the wider population, with over a third affected, but services in London are failing to provide adequate support, a health committee in the capital found last month.

Last year, London's leading LGBT mental health charity, Pace, closed due to lack of funding after 30 years.

For the most vulnerable LGBT people, who don't feel safe at home, at school, or on the street, the consequences of the closure of LGBT venues can be grave: increased alienation, depression and vulnerability to physical attack, Walters said.

"The loss of supportive inclusive venues means that young LGBT people can struggle to find out about services offering help to prevent their homelessness," Lucy Bowyer, coordinator at the LGBT homelessness charity Albert Kennedy Trust, said.

Activists attending the town hall meeting also wanted to use LGBT history as a way of challenging the public perception that the fight for equality is over.

"I'm fed up with people thinking everything is well and fine for the LGBT community," Nigel Harris, a campaigner for LGBT rights in north London, said at the event.

"I often explain that it might be okay for some members of our community, then I'll explain about refugees, disabled LGBT people, he added.

"Most people are not out. Most people feel like they can't come out."

(Reporting by Anna Pujol-Mazzini @annapmzn, Editing by Ros Russell. Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters that covers humanitarian news, women's rights, trafficking, property rights, climate change and resilience. Visit http://news.trust.org)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.