"I know they would come from your belly, but I didn't know how you would make them."

By Ellen Wulfhorst

SANTO TOMAS MILPAS ALTAS, Guatemala, May 3 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - Angela is a gangly, giggly teenager in a Mickey Mouse t-shirt and sneakers. She also is the mother of a baby she bore at age 14 when she had sex with her teacher but did not know where babies came from.

"I know they would come from your belly, but I didn't know how you would make them," she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation at her home in the town of Santo Tomas Milpas Altas about 20 km (12 miles) south west of the capital Guatemala City.

Like Angela, many girls and women in Guatemala have unwanted pregnancies due to a lack of information about sex and their own bodies and endemic violence, according to women's healthcare campaigners.

Indigenous and female: life at the bottom in Guatemala

Guatemala has one of the highest rates of teen pregnancy in Latin America, putting girls on a path to poverty and dependence rather than school or decent work.

Government statistics cited by Planned Parenthood Federation recorded more than 5,000 pregnancies by girls under 14 in 2014 - and in four out of five cases the offender was a close relative such as a father, uncle or grandparent.

One quarter of the children in Guatemala were born to adolescent mothers in the last five years, data shows.

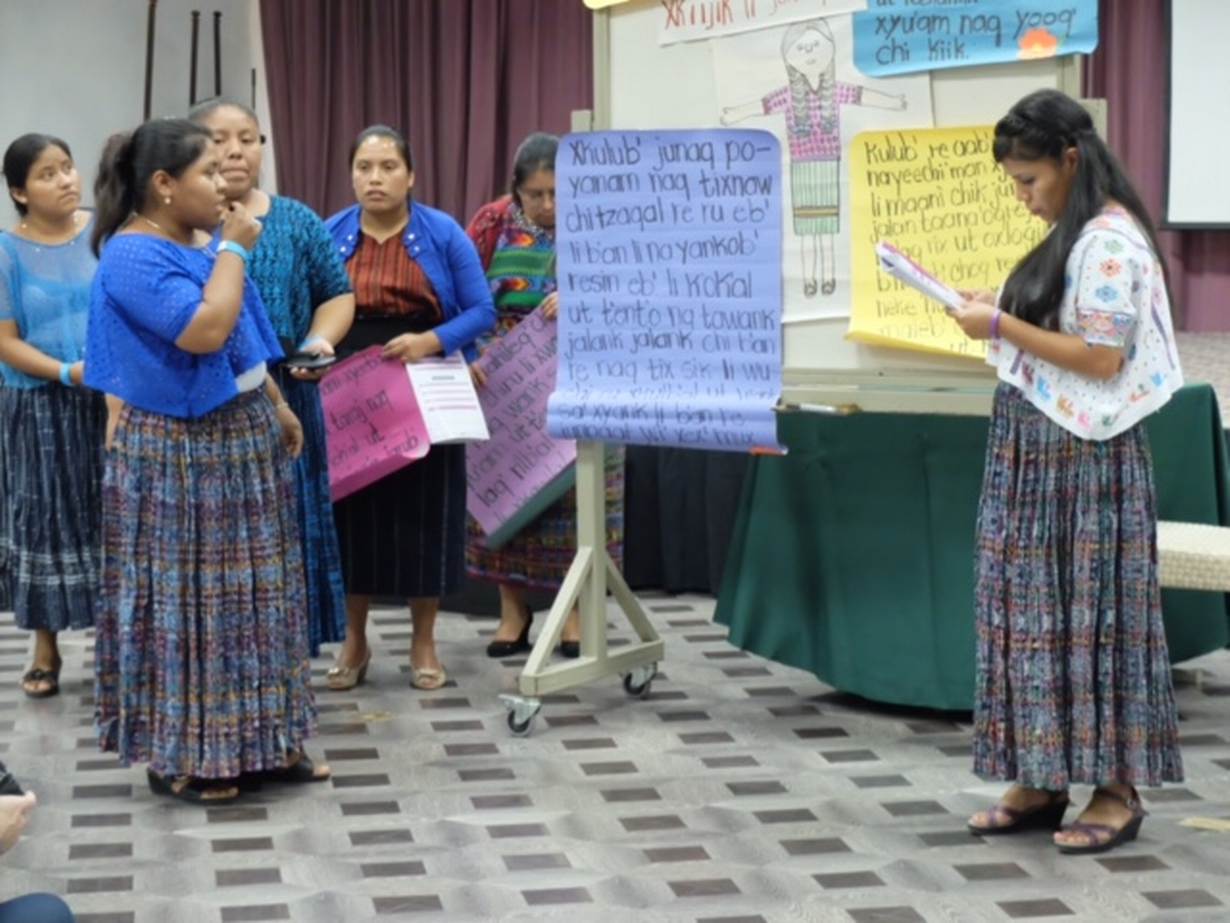

Ignorance about reproduction is rooted in traditional culture and teachings of the Catholic Church and evangelical churches, where girls learn that talk of sex is shameful or forbidden, said volunteers with mentoring program Abriendo Oportunidades (Opening Opportunities).

Mothers often do not know how to tell daughters about their menstrual cycle, and the secrecy is compounded because so many pregnancies are caused by sexual violence within families, according to campaigners.

"Mothers are not informed, and mothers feel ashamed that they cannot even tell the names of the body parts," Marta Alicia Caz Macz, 22, who works with Abriendo in Chisec near the Mexican border, told the Foundation.

SEX EDUCATION

Sex education is taught in schools but campaigners say it is often incomplete or irrelevant, given that fewer than half the girls in Guatemala attend secondary schools.

Maternal health and reproductive services are often expensive and unavailable to those living in the country's vast highlands, far from cities.

High levels of sexual violence against women and girls are said to stem from the low status of women, especially indigenous Mayan women, in Guatemala's patriarchal and macho society.

Guatemala has one of the highest rates of violent deaths among women. Two women are killed every day, according to the UN Women, citing government statistics showing 748 women were killed violently in 2013.

FACTBOX-Ten facts on Central America's most populous country - Guatemala

But the country is making an effort, with 15 percent of revenue from a tax on alcoholic drinks used to fund reproductive health and family planning which raised about US$7 million in 2015, according to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

Laws were toughened up in 2015 when the minimum age for marriage was raised to 18 from 14 for girls and 16 for boys, although 16-year-old girls can marry with a judge's permission under some circumstances.

Pregnancies in girls under age 14 have been required by law to be reported as acts of rape since 2014.

Legal abortion is barely an option, prohibited unless the health of the mother is in danger. An estimated 66,000 illegal abortions are performed each year.

When the Dutch organization Women On Waves arrived by sea off Puerto San Jose in February to offer free abortion pills, the campaign boat was detained by Guatemala's army and the crew was prevented from picking up women seeking to end pregnancies.

"GOOD LAW"

Angela, now 15, said the father of her child was her elementary school teacher, seven years her senior, whom she has since married. She dropped out of school but went back.

By law, her wedding would now be illegal and her pregnancy an act of rape.

"I think it's a good law," said Angela. "When you think there is this law there, maybe you won't do it."

The teen lights up as she describes 15-month-old daughter Brithanny Lupita, who she says is chubby and "likes to break things."

Angela gets contraceptive implants from WINGS, a reproductive rights organization and wants no more children.

She wants to be a baker when she grows up "because I like to eat cakes," she said with a laugh.

VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN

By age 19, most women in Guatemala have two children, said Alma Odeth Chacon of Tierra Viva, a rights organization.

"It becomes a vicious cycle of poverty and violence, and we are not able to break free," she said.

Leaving girls at risk of early and unwanted pregnancies is an effective means of power and control, said Justin Sitron, a professor at the Center for Human Sexuality Studies at Widener University in Pennsylvania.

"If women continue to experience oppression and marginalization in a power structure, they will not have the time and energy to advocate for themselves or to try to disrupt the power that men retain," he said in an interview.

Hoping to break the cycle is Alicia Perez, 19, who gets contraceptive injections in Guatemala City at an Asociacion Pro-Bienestar de la Familia de Guatemala (APROFAM) clinic.

She has a 3-month-old boy, all the children she and her husband can afford for now, she said. She makes rellenitos, a dessert of beans and plantains; her husband is a street vendor who sells flavored crushed ice.

Perez is the first in her family to use contraception.

"I want a small family. Bigger families will have more challenges and poverty," she said.

Elvira Margarita Cuc Cho, 24, a mentor with Abriendo in Chisec, said too many girls and women are ignorant, recounting the story of her cousin who unwittingly got pregnant at age 17.

"She didn't know what was happening. It wasn't until her body started to change that her mother told her, 'You're pregnant.'"

Forced to wed the father, she is locked in a violent marriage, with bruises to show for it.

"She is very ashamed and doesn't want to talk about it. She just says she hurt herself," she said. (Reporting by Ellen Wulfhorst, Editing by Belinda Goldsmith; Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers humanitarian news, women's rights, trafficking, property rights, climate change and resilience. Visit http://news.trust.org)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.