* Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Thomson Reuters Foundation.

We cannot tolerate our colleagues being targeted deliberately or harmed indiscriminately. The system must change

Late last year, a bunker buster bomb shot through an underground shelter in Syria’s Hama province. A group of aid workers were taking shelter inside at the time. Nine of them, all Syrian, were killed instantly.

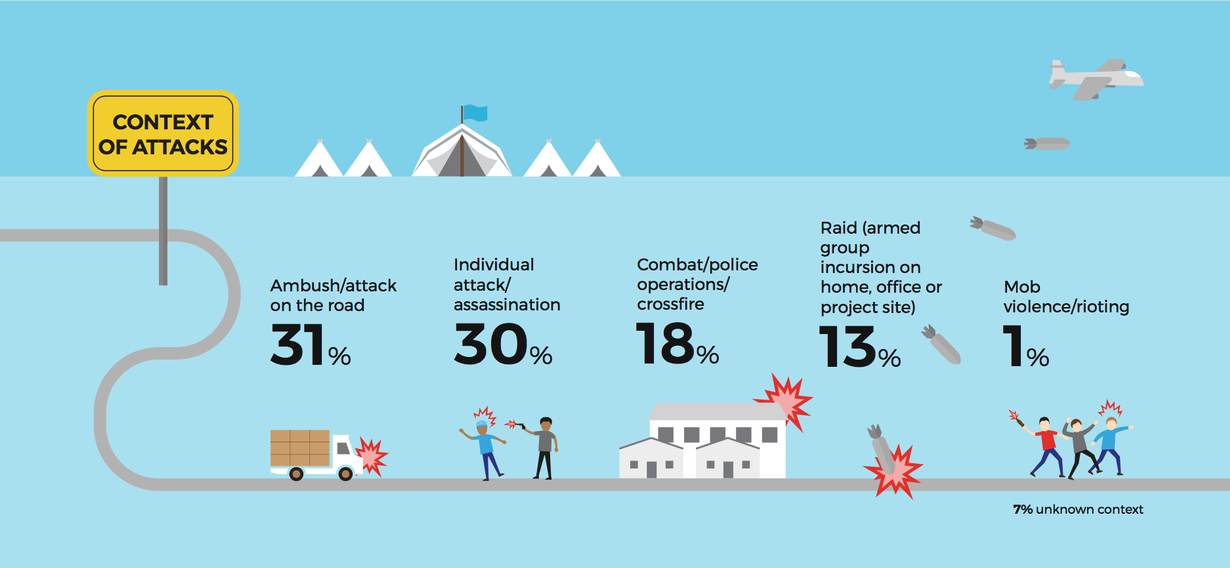

In February, six Red Cross workers were shot dead in an ambush in northern Afghanistan while travelling through the desert to deliver livestock supplies to people in need. Their vehicles were clearly marked as humanitarian. The International Committee of the Red Cross described the incident as the worst attack against them in 20 years.

Then just last week, another six Red Cross volunteers were killed in the Central African Republic while they held a meeting at a health facility in Mbomou.

In the last two months alone, relief workers have been shelled, shot at, kidnapped and killed in Afghanistan, the Central African Republic, Somalia, South Sudan and Syria.

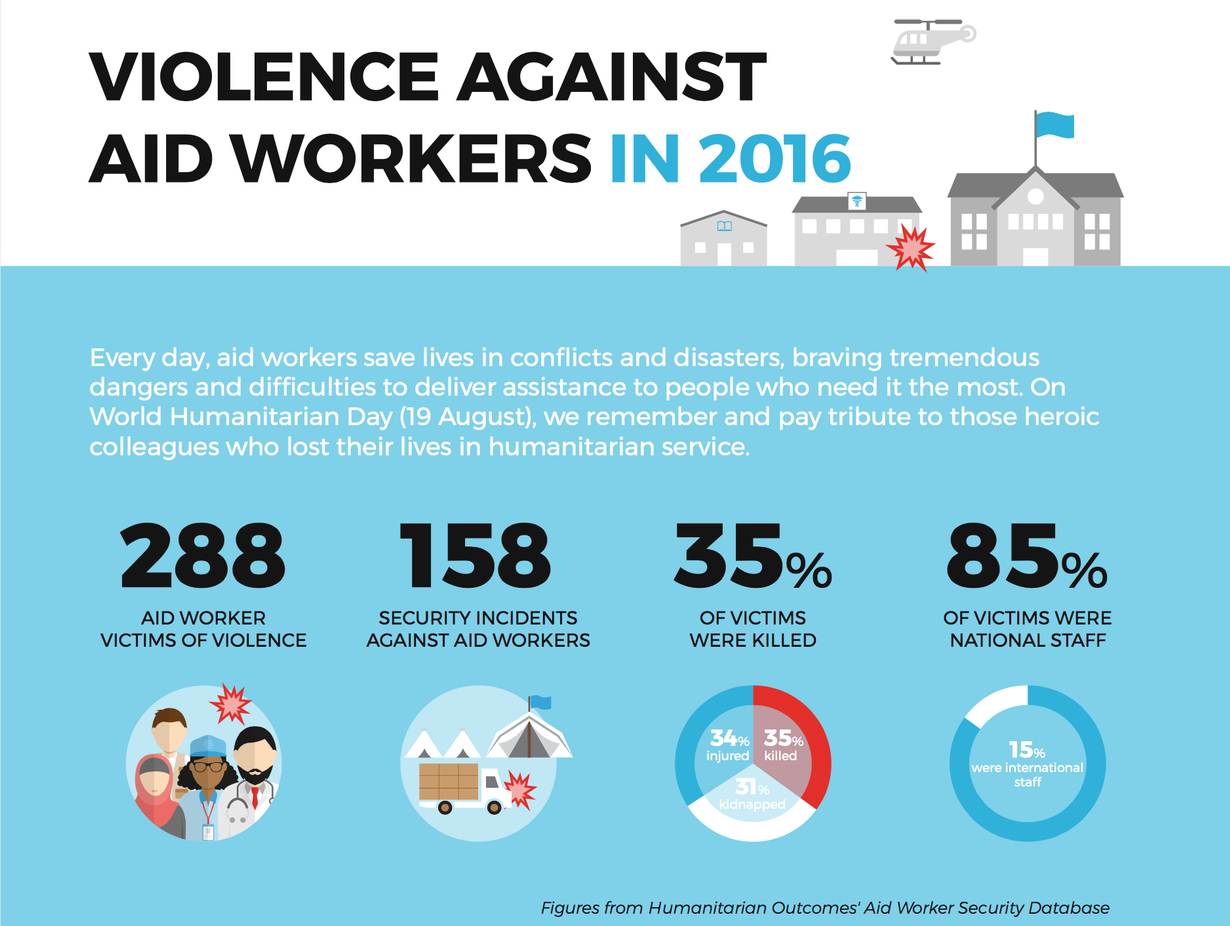

In 2016, 158 major planned attacks targeting aid operations killed 101 aid workers, wounded 98 and kidnapped 89. The clear majority of those killed and injured - 85 per cent - were national staff of humanitarian organizations.

One thing is clear, respect for the rules of war has collapsed in too many places. Aid workers assist the world’s most vulnerable people. This means they work in active war zones, knowing the risks they face. But unlike combatants, aid workers are not party to any conflict, they are there to deliver life-saving assistance to people faced with the worst scenario one can imagine - war.

On 19 August every year, aid workers around the globe pause to mark World Humanitarian Day. On this day, we take the opportunity to honour and remember our colleagues, friends and family members who have been killed on the frontlines of crises, and to salute them for their sacrifice and service. We also come together in solidarity with the millions of civilians caught in conflict, to demand that world leaders exert all the diplomatic, political and economic influence they can to ensure parties to conflict protect civilians.

Wars without limits

Attacks are becoming increasingly brutal in nature where international humanitarian law continues to be eroded.

In one of the most heinous attacks against humanitarians in South Sudan’s war, on 11 July 2016 dozens of government soldiers entered the Terrain residential compound sheltering aid workers in Juba. They gang-raped several of the female aid workers, and executed a journalist while forcing the others to watch. No one should ever endure this senseless barbarity. By such acts, the soldiers sent a message to the humanitarian community - that our neutrality is not respected and that we are not shielded as humanitarians.

In other conflicts, the delivery of aid is hampered by fighting parties, as a tactic to prevent life-saving relief reaching communities living on the ‘wrong’ side of the frontlines, leaving communities deprived for years on end.

Medical staff in particular are often singled out for attack, with profound long-term consequences for healthcare to communities in desperate need. In 2016, 979 medical staff were killed or injured in attacks against medical workers and facilities.

Two Médecins sans Frontières-supported hospitals in Yemen were targeted by airstrikes in 2016, even though the organization shared the GPS coordinates with the conflict parties, and clearly marked the building roofs. Between them the hospitals served over 270,000 people.

Many incidents have never been investigated, and in the rare instances when investigations have been carried out, they have often failed to meet international standards.

This sends a direct message to the perpetrators; that violence against humanitarians is permissable, and that fighting parties can flout their obligations to respect international humanitarian law with virtually no consequence. So few people have been held to account that no official recorded number exists.

While some attacks are committed by non-state armed groups, when measured by body count alone, it is states that are responsible for the highest number of aid worker fatalities. Fifty-four humanitarians were killed by state actors in 2015 and 2016.

Stay and deliver

The repercussions of attacks on aid workers go far beyond the staff themselves – these attacks deny conflict-affected people the aid they so critically need. They deprive children of life-saving treatment, obstruct families from receiving food, and rob communities from accessing shelter.

We cannot tolerate our colleagues being targeted deliberately or harmed indiscriminately. The system must change. Three concrete things can be done to better protect aid workers.

Firstly, states must investigate and prosecute serious violations. States, particularly the most influential ones, must demand that warring parties, including their own forces, respect international law and hold perpetrators to account.

In South Sudan, intense international pressure led to a small number of the soldiers accused of the Terrain compound attack being brought to trial. If this trial brings some measure of justice, it will show what is possible. But diplomatic pressure must be consistent. Few, if any, of the dozens of subsequent attacks against humanitarians in South Sudan since then have brought those responsible to account.

Secondly, aid organizations must always demonstrate their neutrality. We must denounce those who use aid or access as bargaining chips, holding the most vulnerable hostage. We must push against those who want to make aid a tool to reach other political objectives. If we are to help people most in need, aid must be impartial and neutral. If not, we risk becoming partisan and politicized, and targets of attacks.

Finally, we must provide better duty-of-care to all staff on the frontlines, particularly national staff. International aid agencies are increasingly providing aid remotely in highly insecure environments. This means they are delivering relief through local partners and transferring the risk to them. Local and national partner organizations face an inadequate level of security and support from their international partners. We must provide better security training to equip them in the field, as recommended by the recent Presence and Proximity report on aid workers. Donors and international partners should ensure that national partners’ security needs are factored into proposals and budgets, so they have the resources needed to protect their staff.

Making these changes is urgent and vital for the survival of many lives and lifelines. Today, over 141 million people desperately need humanitarian assistance, the vast majority of them affected by conflict – the highest number since records began. We cannot afford to let them down.

Wars have rules. It is time to enforce these rules, rather than have brave aid workers needlessly risk their lives, and too many of the most vulnerable to be left alone in the crossfire and lose theirs.

Jan Egeland is Secretary General of the Norwegian Refugee Council and a former Emergency Relief Coordinator. Stephen O’Brien is UN Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator.