"We as victims, who have lived through this disaster, we can put ourselves forward as an example to bring peace"

By Inna Lazareva

N'DJAMENA, Oct 26 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - Ginette Ngarbaye, 52, rises from her seat, leans forward and glares intensely at the ghost of her tormentor.

"I gave him a long, deep look - like this," she said, recalling how she came face to face with former Chad President Hissène Habré - the man responsible for the worst moments of her life.

Aged 20, she was arrested by Habré's soldiers, interrogated, tortured and raped – all while pregnant with her first child. Unable to get medical help, she gave birth on the cement floor of her cell, crowded with other women and crawling with insects.

"I don't even know what was used to cut the umbilical cord," she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation, wiping away droplets of sweat in the dusty courtyard at the home of a friend whose husband was abducted and killed in 1984.

But since Ngarbaye confronted Habré three decades on, delivering her testimony in a Dakar courtroom in 2015, she feels victorious, and still keeps a photo of the encounter.

Habré seized power in Chad in 1982, and imposed one-party rule. He waged a campaign against ethnic groups, including the Sara, Hadjerai, Zaghawa and Chadian Arabs, and others perceived to be opposed to his regime, carrying out arbitrary arrests, torture and political assassinations through his security agency.

After being ousted in a 1990 coup, he fled to Senegal. Two years later, the Chadian Truth Commission accused his government of being responsible for 40,000 murders and 200,000 cases of torture, but he was not arrested until 2013.

His conviction in May 2016 for war crimes and crimes against humanity sent shockwaves throughout Africa - marking the first time in modern history that one country's domestic courts have prosecuted the former leader of another on rights charges.

Other such cases have been tried by international tribunals.

"This Habré case showed that victims, with tenacity and perseverance, can actually create the political conditions to bring their dictator to court," Reed Brody, an American lawyer who has helped Habré's victims, said by email.

Many of those survivors, now in their 60s and 70s, are not resting on their laurels.

Every Saturday morning they gather in N'Djamena as they have done for the past 26 years. Today their objective is even more ambitious – to ensure justice is done not only for themselves but also for other victims of rights abuses across Africa.

"NEVER AGAIN"

"We think the Habré trial serves as an example for all of Africa and beyond, where many people are killed and there are major violations of human rights," said Clément Abaifouta, president of the Chad victims' association, who spent four years in one of Habré's prisons, earning the nickname "gravedigger" due to his job burying the bodies of detainees in mass ditches.

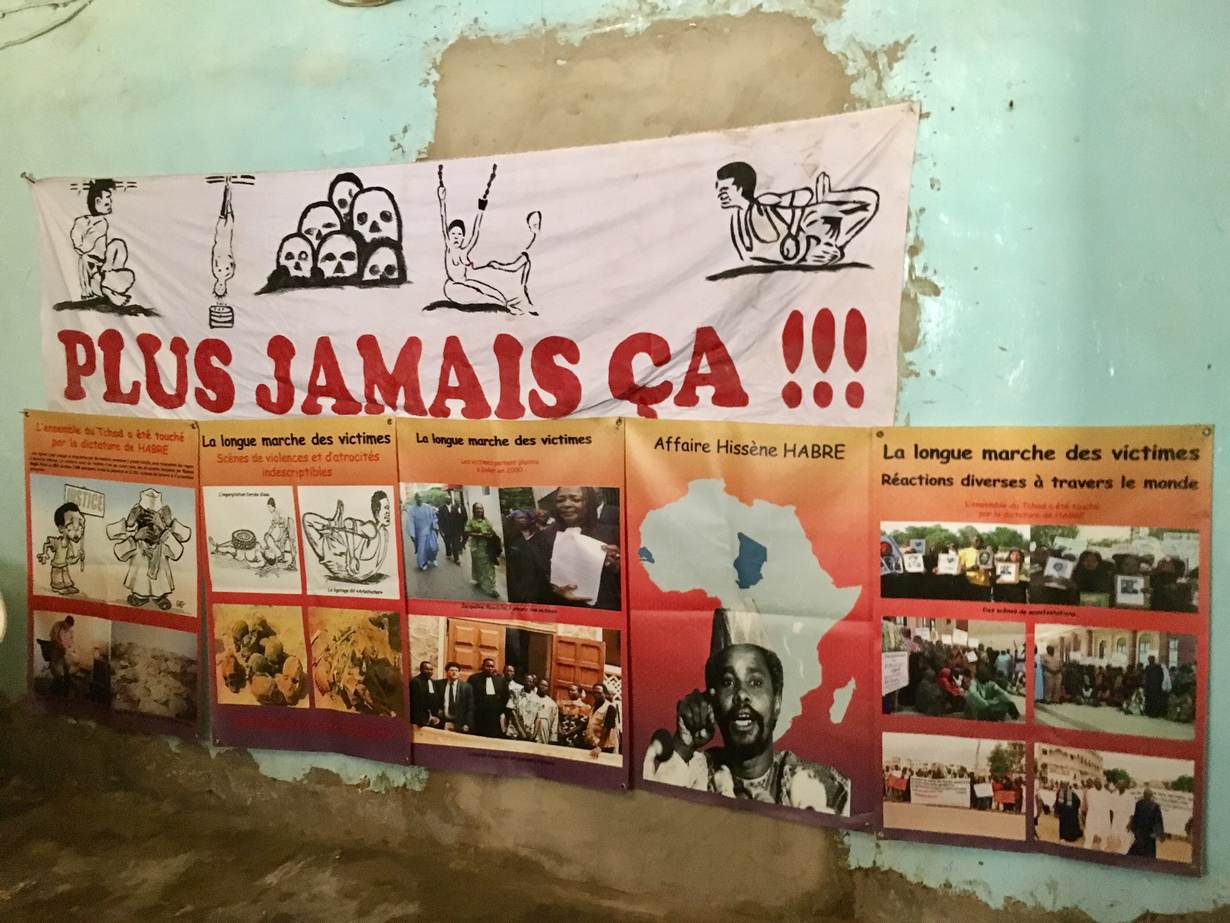

Sitting in the association's dilapidated headquarters, Abaifouta pointed to a large poster on the wall with fat red letters stating "Never Again This!!!"

Above, sketches spell out exactly what that means: a woman bound in chains writhing in agony as a match burns her nipples; a man tied and hung upside down from the ceiling; a collection of human skulls piled on top of one another.

Today, only between 7,000 and 9,000 of Habré's victims - who may have numbered about a quarter of a million - are still alive, said Abaifouta.

"But look at what's happening in Burundi, in Gabon, in Syria - what's happening everywhere," he said. "The experience of Habré's victims can be used to bring justice in other countries."

In April, they met survivors of alleged atrocities committed by Gambia's former leader Yahya Jammeh. He is accused of rights abuses, including unlawful detention, torture and murder of perceived opponents - charges the ex-president's supporters deny.

This month, Jammeh's victims launched a campaign to bring him to justice with the help of Brody who was instrumental in the Habré legal process.

The Chadian activists are also sharing their experiences with young people, using extracts from Habré's trial as training materials, to prevent such atrocities from ever happening again.

"We as victims, who have lived through this disaster, we can put ourselves forward as an example to bring peace, well-being, reconciliation and a peaceful coexistence," said Abaifouta.

WAIT FOR COMPENSATION

The most pressing challenge for the victims is accessing financial compensation, which is still pending.

In April, the appeals court in Senegal ordered Habré to pay 82 billion CFA francs (about $144.5 million) in compensation, listing nearly 7,400 people as eligible and mandating a trust fund to search for and seize the former dictator's assets.

Two years earlier, a Chadian court ordered the government to pay more than $60 million in reparations, erect a memorial, and turn Habré's former political police headquarters into a museum.

To date, none of this has happened.

"The majority of people really need this money," said Ousmane Taher, the association's liaison officer. "His victims are now old, they have suffered so much, they don't have a job - they are waiting for this money to be able to take care of themselves."

Senegal has frozen some of Habré's assets, including a house in an upscale Dakar neighbourhood and some small bank accounts, said Brody. "But Habré emptied out the Chadian national treasury in the days before his flight to Senegal, and we believe his assets are much more extensive," he added.

The trust fund mandated by the Dakar court can also collect voluntary contributions – but the statutes governing it have yet to be approved by the African Union (AU).

REDRESS, a UK-based group working on justice for torture survivors, said it did not know the cause of the delay, and urged the AU to act at its upcoming summit in January.

The AU did not respond to a request for comment.

For now, the Chad victims' association has set up a savings and loans group, which helps people access cash in times of crisis.

RAPE AS A WAR CRIME

Experts are also hoping the Habré trial will serve as an incentive to press for more convictions of rape as a war crime.

The judgment centered on sexual violence - a rare outcome at war crimes tribunals, Kim Thuy Seelinger, director of the sexual violence programme at the University of California, Berkeley, wrote in a journal article this year.

Rape was declared a war crime in 1919 after World War One, but only in 1998 did the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) first successfully charge former Rwandan mayor Jean-Paul Akayesu with using rape as a weapon of war.

The ICTR's successor, the International Criminal Court, went on to issue its first rape conviction in 2016 when it held Democratic Republic of Congo's Jean-Pierre Bemba responsible for a campaign of rape and murder in Central African Republic.

But the Habré case points to the difficulty of securing successful prosecutions. Habré was convicted of rape, as well as sexual crimes committed by his security agents, yet he himself was later acquitted of rape on procedural grounds because a key testimony came too late.

To prevent that happening again, "we must do more to support earlier disclosure of sexual violence", wrote Seelinger.

As one of those who spoke out about rape by Habré's soldiers despite the social stigma, Ngarbaye said people had mocked her and other witnesses for testifying against a man and a regime that had seemed all-powerful.

Their courage was vindicated by Habré's conviction.

"We waited so long (for justice) - and finally it came," said Ngarbaye.

(Reporting by Inna Lazareva, editing by Megan Rowling and Kieran Guilbert; Please credit Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers humanitarian news, women's rights, trafficking, property rights, and climate change. Visit news.trust.org)

The Thomson Reuters Foundation is reporting on resilience as part of its work on zilient.org, an online platform building a global network of people interested in resilience, in partnership with the Rockefeller Foundation.

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.