* Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Thomson Reuters Foundation.

We live this lifetime in a world that seems to seek to regularise, commodify and normalise everything to maintain an illusion of control over reality. We are granted, perhaps only rarely, moments of grace. Raw, unfiltered, in-your-face, undeniable, can’t-turn-away instances of what it really is to be.

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) doctor Ashraful Bhuiyan and supervising midwife Tania Akter let me join them the other day to get a more informed in-depth idea of their work. Balukhali (TV Tower) Telipara Camp in Cox’s Bazar District is part of the sprawl of Rohingya refugee settlements that are growing by the day.

We visited a UNFPA temporary service site, the third of five clinics that we stopped at over an eight-hour period. This is a newish facility, put up in the last week or so and really just a big tent. It’s supposed to be a women-only facility built with UNFPA’s implementing partner Hope Foundation, but on this particular day men were there constructing areas that could be used for private consultations or assessments.

Since August 27 at least 67,000 women have been screened by UNFPA and partners at places like these. Some 15,000 are pregnant women or new mothers and their infants. They see midwives and reproductive health workers first. So far there are only seven facilities and 42 midwives; and they are often the first people that Rohingya women in difficulty turn to. UNFPA is hoping to get more funding to scale up these lifesaving services.

The tents are always full to overflowing with women and their small children on weekday mornings. The midwives work on rotation and are available around the clock every day if necessary. Tania told me she delivered 12 babies in 12 days last month. One mother delivered on the way from a camp to the birthing unit. Sometimes the midwives will go to the makeshift shelters, teeming with refugees to help women get through labour and deliver babies in squalid conditions, often without sanitation, and where water, food and healthcare are scarce.

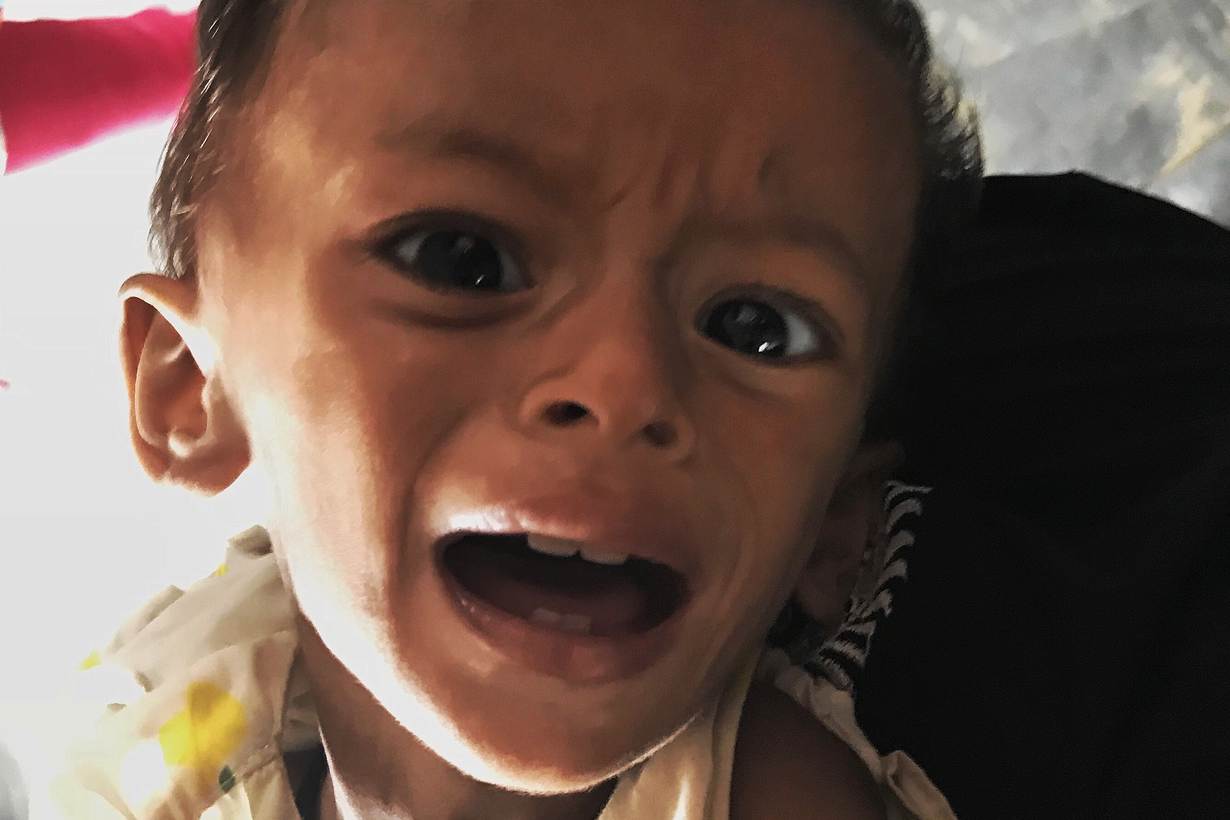

One woman we met that morning had come from just such a shelter a few hundred metres away with her 11-month daughter. The noise of hammering, the doctor giving instructions, midwives discussing their clients continued. But my attention was drawn to this daughter, this mother. The baby may have been 11 months old but she only weighed as much as a 6-month-old. She had the telltale signs of extreme malnutrition from lack of protein and carbohydrates, and she would not settle, squirming and crying out in her mother’s arms. Her eyes were too big for her face, filled with an anguish of an infant that’s felt prolonged hunger no baby should ever feel.

Her mother, who did not speak, seemed used to juggling the baby around in her arms, her heart seemingly accustomed to the baby’s wrenching cries. She married when she was just 15, five years ago. She also has a two-year-old and is currently 6 months pregnant. Her own eyes were hollow and dark and gazed assentingly at me as I looked back at her and wondered what had happened to her. Still the baby cried and squirmed. The hammering and noise of builders kept going. I signalled that I’d like to take the baby, knowing how tiring it can be in her place. She handed her over in the natural way women have always shared child care, so I took her little skin-and-bones body and rocked her as I’d rocked my own children at that age, tried to get her to look at me, singing a little.

Doctor Ashraful told me this infant had probably been malnourished her whole life, even in the womb. Tania explained every single Rohingya mother she helps is either undernourished or malnourished. Through the years I’d seen images of such children taken in the camps in Rakhine State where Myanmar authorities have long forced some 100,000 Rohingya to live, with little to no aid getting through for huge stretches of time. Some of those children died of hunger, little more than skeletons.

Doctor Ashraful spoke to both parents (the father had turned up), got their contact details, prescribed dietary supplements and told the team to make sure the family were given high-energy biscuits that he’d just arranged with Action Against Hunger to be delivered and handed out to all pregnant women that come here.

Still the baby would not settle. No amount of cuddles will stop her cries. She needs food. Her mother and father need food, and a proper shelter with even just basic services.

Her pain, her cries, seemed to stop time, nothing else mattered. This child demanded my attention in a way that forced me to understand profoundly matters of life and death, humanity and the depths of the cruelty to which she and her people have been subjected. I could not and would not turn away.

Her eyes met mine, shone with despair, pleading and furious. Help me, help me, help me.

We’re trying, baby. We’re trying.

Veronica Pedrosa worked in Cox’s Bazar as UNFPA communications consultant.