"I am trapped and any move I make, I get stuck even more."

By Emma Batha

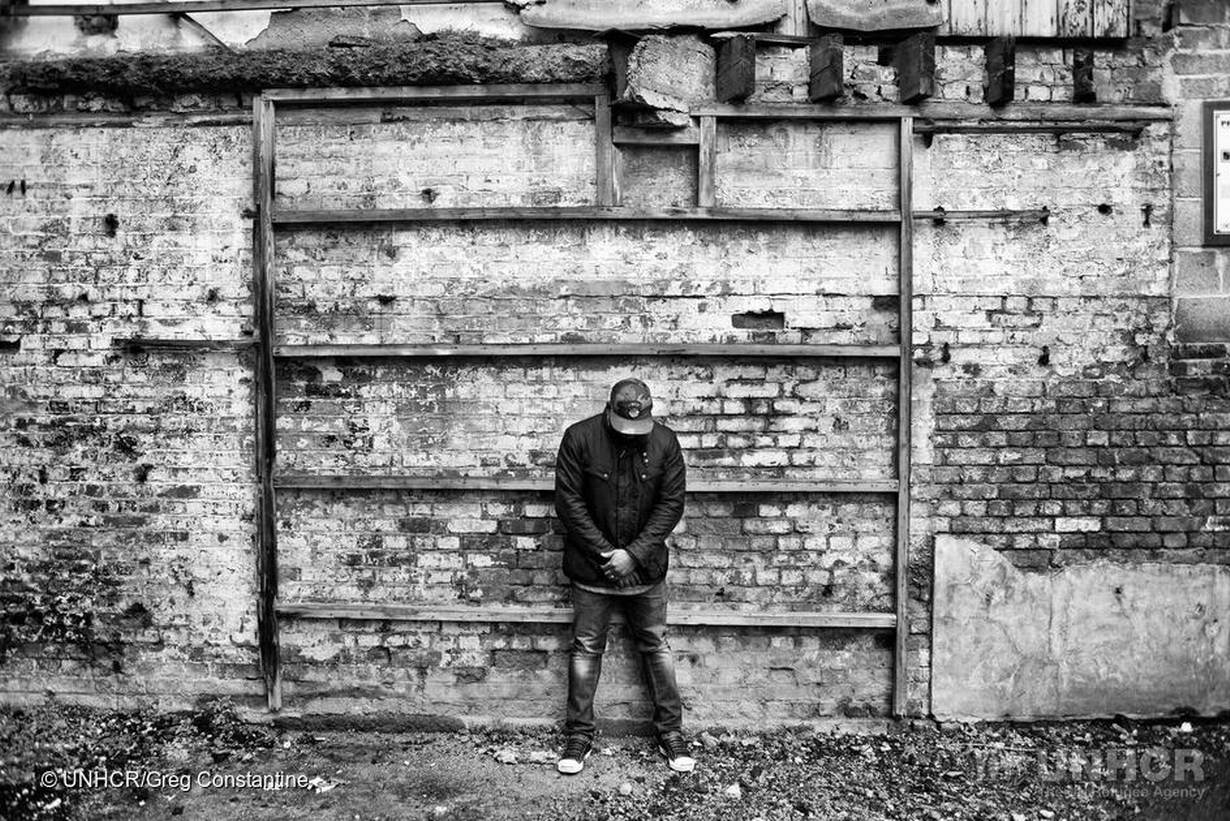

LONDON, Nov 30 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - The man in the photo leans against a derelict wall, his head down, his face obscured. He looks crushed and alone.

The image is part of a show at London's prestigious Saatchi Gallery called "Nowhere People UK" – the first exhibition to focus on Britain's invisible stateless people.

Sometimes referred to as "legal ghosts", stateless people are not recognised as nationals by any country. They live in the shadows, deprived of basic rights most people take for granted.

"What for me was so eye-opening was the sheer sense of rejection and isolation that stateless people in the UK expressed to me," said American photographer Greg Constantine.

"And how paralyzing that feeling was for them in their day to day lives."

Charity Asylum Aid estimates several thousand stateless people are living in Britain, often at risk of destitution, exploitation and prolonged detention.

Some were born in countries that do not recognise them as nationals, others have fled war or rights abuses, or are victims of trafficking.

Constantine has spent a decade photographing stateless communities around the world including the Rohingya in Myanmar, the Roma in Europe and the Bidoon in Kuwait.

But he said the isolation experienced by stateless people in Britain was unlike anything he had seen before.

Constantine told the Thomson Reuters Foundation he was particularly moved by a bright young Bidoon man who was keen to study and have a career.

"I'm trying to apply for work but I'm not allowed," the man says in a caption accompanying a photo of his shadow. "I want to go to university ... but I'm not allowed. I've tried to get a driver's license, but I'm not allowed."

The man said he had spent years in limbo in Britain, which has refused him asylum but cannot deport him because Kuwait has rejected him as a citizen.

"It is like a spider web," he added. "I am trapped and any move I make, I get stuck even more."

HIDING IN A FOREST

Constantine said most of the stateless people he met had been detained, sometimes multiple times. One man had spent three and a half years locked up.

Others were homeless - one had ended up living in a forest.

None of the people photographed was willing to give their real name and only two allowed their faces to be fully shown.

"The very fact they did not want to have their identities revealed (shows) the repercussions statelessness has on an individual," Constantine said.

One photo features a 27-year-old Kurdish woman born in Syria, who asked to be called Maya.

"You are not seen as a person," said Maya, who has since been granted British nationality. "I felt like I didn't exist because I was not recognised anywhere."

The U.N. refugee agency (UNHCR) has launched an ambitious campaign to end the plight of some 10 million stateless people worldwide by 2024.

Gonzalo Vargas Llosa, the UNHCR's representative in Britain, said Constantine's photographs shone an important spotlight on a human rights issue that remains hidden.

"For people without a nationality, life is on hold," he said.

Britain is one of only a handful of countries to have set up a procedure to identify stateless people, and provide them with a route to legal residency.

But Asylum Aid said there was a backlog of applications, and even those recognised as stateless faced difficulties acquiring British citizenship.

Constantine said one of the most tragic aspects of statelessness was the way it destroyed a person's self-worth.

One man pictured leaning against a grill gate describes his feelings of entrapment as life passes him by.

"I'm like a bird in a cage," he says. "All I can do is watch."

(Editing by Katy Migiro. Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, which covers humanitarian news, women's rights, trafficking, corruption and climate change. Visit news.trust.org to see more stories.)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.