* Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Thomson Reuters Foundation.

As a photographer for the ICRC I’m used to seeing difficult imagery of people caught in conflict. But little could prepare me for what I would encounter as I traveled through Central America and Mexico, as I followed the migration route. I met families of missing migrants, who were desperate for any sign of life from their loved ones. The anguish of not knowing was a pain that they had endured for many years.

I started my two-week journey in Honduras, interviewing parents, whose children had gone missing, then I travelled north, following the migrant routes north towards the United States. The parents’ stories stayed in my head the entire trip north through the lush green landscapes of Guatemala and Mexico.

The journey for migrants is exceptionally dangerous. They travel hundreds of miles mostly on foot. They have little money. They often run out of food. They often run out of water. They get sick or they have accidents. But most of all they are incredibly vulnerable – away from their countries and their comfort zones. They can be attacked or cheated all along the route.

One mother told me how her son was a strong swimmer. He had gone missing, but she was sure he had not drowned.

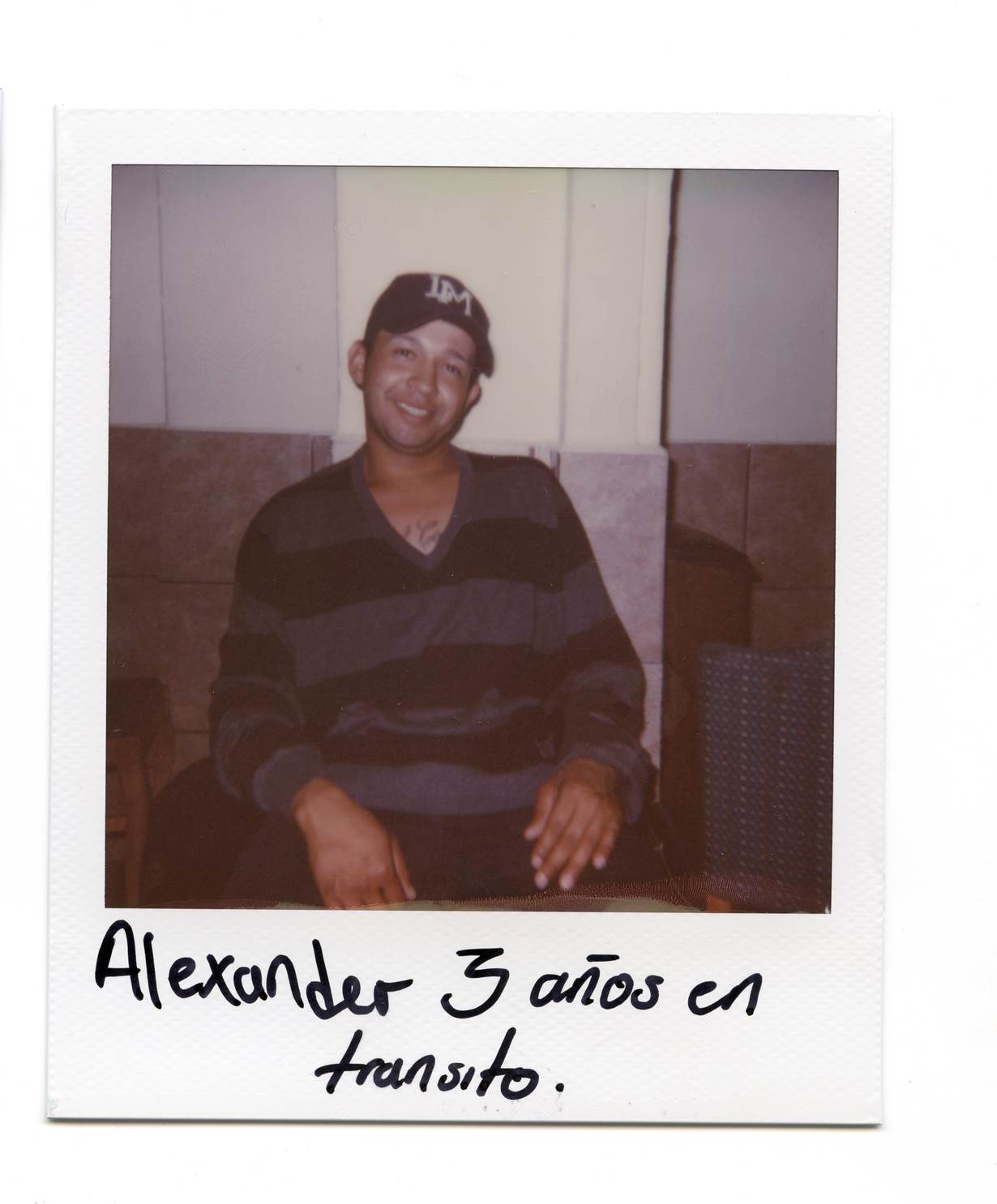

I wanted to tell human stories. I used polaroids so the migrants could handwrite messages to family and friends. They wrote about what they thought mattered to them: a love letter, a note of warning. When we showed the polaroids, many migrants recognized people they had met or travelled with earlier in their journey.

When somebody goes missing, it causes unimaginable pain for their families. Their friends, colleagues, and societies too. There are so many layers of suffering when somebody goes missing. With our partners in Red Cross or Red Crescent societies, the ICRC provides some help. Tracing lost family members. Reuniting parents with children. Psychosocial support can help mothers to retake control, sometimes just of the little things in their lives.

Discovering the fate of missing people is first and foremost a humanitarian act. And it is an intensely personal one too. One mother sang a hymn for us, asking God to help her son. Another told us about a dream she had been having for years. In the dream, she is praying to God beneath her mango tree, asking him for news of her son. One way or the other. But just to know.

Now missing, the migrants left photos with their parents and these photos reminded me of my own family - a Christmas tree, a school pageant. These were incredibly important moments that families shared with us and it helped put me in the shoes of the mothers and fathers who are missing their kids, some of them for 15 years.

For three weeks in June 2017, Kathryn Cook met the families of missing migrants in Guatemala, Honduras and Mexico and travelled with migrants walking the route. The photographs and testimonies she collected were made into a powerful new website – missingmigrants.icrc.org – that tells these stories in the pictures and words of the migrants and families themselves.