"At the peak of the epidemic, no treatment was available. We had a lot of orphans, a lot of widows, a lot of widowers"

By Lyndsay Griffiths

MAZABUKA, Zambia, Dec 12 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - Sugar brought a rush of people and prosperity to the drab highway stop in southern Zambia they now call "Sweet Town" - and with that trade came AIDS.

To mine copper or cut cane, outsiders descended on scruffy, fast-growing towns like Mazabuka, hoping to make a new life and where the men went, a sex industry followed with local women touring bars, inns and truck

It was a perfect storm for the AIDS epidemic.

"There was a huge mobile population and the district was simply too overwhelmed with men who came without their spouses," Jabez Kanyanda, an expert on AIDS, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation during a tour of the Southern Province of Zambia where he leads an HIV prevention programme.

Zambia was one of the world's

HIV prevalence

"At the peak of the epidemic, no treatment was available. We had a lot of orphans, a lot of

"The doctors knew, of course, but there was nothing they could do ... Every day, you'd pass the graveyard and see people moaning, wailing - yet another funeral."

The roadside graveyard adjoins the hospital - a crowded field of makeshift memorials and formal headstones, trees arching over red-earth mounds that mark the many dead.

Hand-scrawled signs point to an agony of lost babies: "beloved daughter Gladsy Mainza" aged two; nearby lies Tia Jonga, who died on Nov. 7, at under four months old.

"In our hospital setup, every bed space was taken by someone with HIV. In the mortuary, every day, two, three dead bodies," Stephen Shajanika, Mazabuka's District Health Commissioner, recalled in an interview.

Now the people of Zambia have moved on from the worst and are learning to live with its aftermath, helped by a military-style campaign to spread information, test those most at risk, and prescribe drugs to keep AIDS at bay.

"We are trying to root out every HIV-positive person. We want to find them. We want to test them. We will do our part and then we empower people who take it very seriously," said Kanyanda.

SWEET TOWN

As the centre of the nation's sugar industry, Mazabuka squats on a busy road in land-locked Zambia, a land of transit criss-crossed by truckers from eight neighbouring countries.

As the cane grew, the people followed - pickers from the west, executives from Mauritius and South Africa, European funders and African lorry drivers. Women had less way to gain.

"I've stopped now but it was just the total poverty. You sleep with men to buy food. We just had no money to pay the house rental," said Beauty, a 34-year-old former sex worker who now sells sausages. "I'm a different women now."

Beauty is not the only one to change.

Testing for the HIV virus is up, knowledge has increased and, most importantly, drugs are available to control the spread of the virus and stop it developing into AIDS.

The United Nations estimates there are still 250 new infections a day in Zambia, but that has dropped 27 percent since 2010 and AIDS-related deaths have fallen 11 percent.

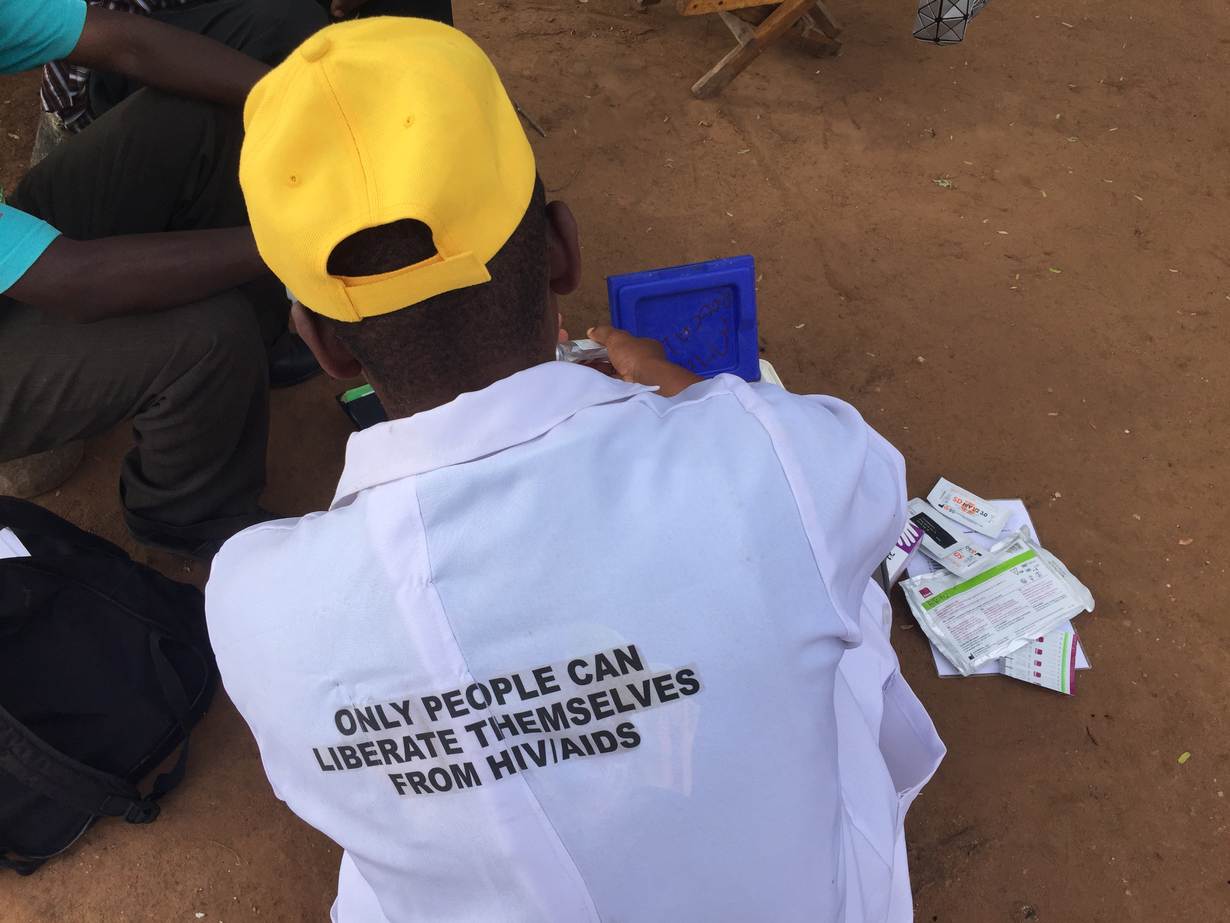

Part of this is due to campaigns like the one run by DAPP, a local NGO that invented a seemingly simple strategy to secure a military-style "Total Control of the Epidemic".

Conducted one-on-one, door-to-door, this all-out war aims to mobilise individuals to control their own health and, to that end, has reached more than 1.5 million of 16.5 million Zambians.

Field officers, special forces and troop commanders man the front and rally the troops - the language is no accident.

"We were going in for a fight," said Division Commander Kanyanda.

"We needed to organise ourselves like military and show we are in a serious business, fighting a fight with a clear line of command."

MILITARY CAMPAIGN

At the grass roots, DAPP field officers go hut-to-hut to share stories, win trust and encourage testing, carrying mobile testing kits - a finger pinprick - giving results in 15 minutes.

Truckers get free condoms and lessons on their usage while former sex workers tour bars to spread the message, and revered chieftains go public about their HIV tests to smash stigma.

Each strand is another part of the "Total Control" strategy, which began in neighbouring Zimbabwe in 2000, came to "Sweet Town" in 2006, then moved to nearby Sinazongwe two years ago.

Sinazongwe's governor - the top government man in a district of nearly 200,000 people - says the plan is working.

"The government will fight HIV/AIDS to the last drop of our blood because it almost wiped out Africans," District Commissioner Protacia Mulenga, the government's top official in the region, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

"But I'm the governor here and believe me, the government cannot reach where DAPP has reached."

Mulenga is no bureaucratic bystander to the epidemic. Two of his brothers died of AIDS. His sister is HIV-positive and he cares for her children.

"I saw my brothers dying in pain. There was no treatment," he said.

"But now when someone has learnt their status, there's a new control ... They refrain from blood sharing and careless sex.

"What we have done in Zambia needs extending to other countries. The best experience was learnt here and it needs to penetrate further."

(Reporting By Lyndsay Griffiths, Editing by Belinda Goldsmith; Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers humanitarian news, women's rights, trafficking, property rights, climate change and resilience. Visit http://news.trust.org)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.