* Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Thomson Reuters Foundation.

The pitfalls of simplification when looking at greenhouse gas emissions from livestock

What we choose to eat, how we move around and how these activities contribute to climate change is receiving a lot of media attention. In this context, greenhouse gas emissions from livestock and transport are often compared, but in a flawed way.

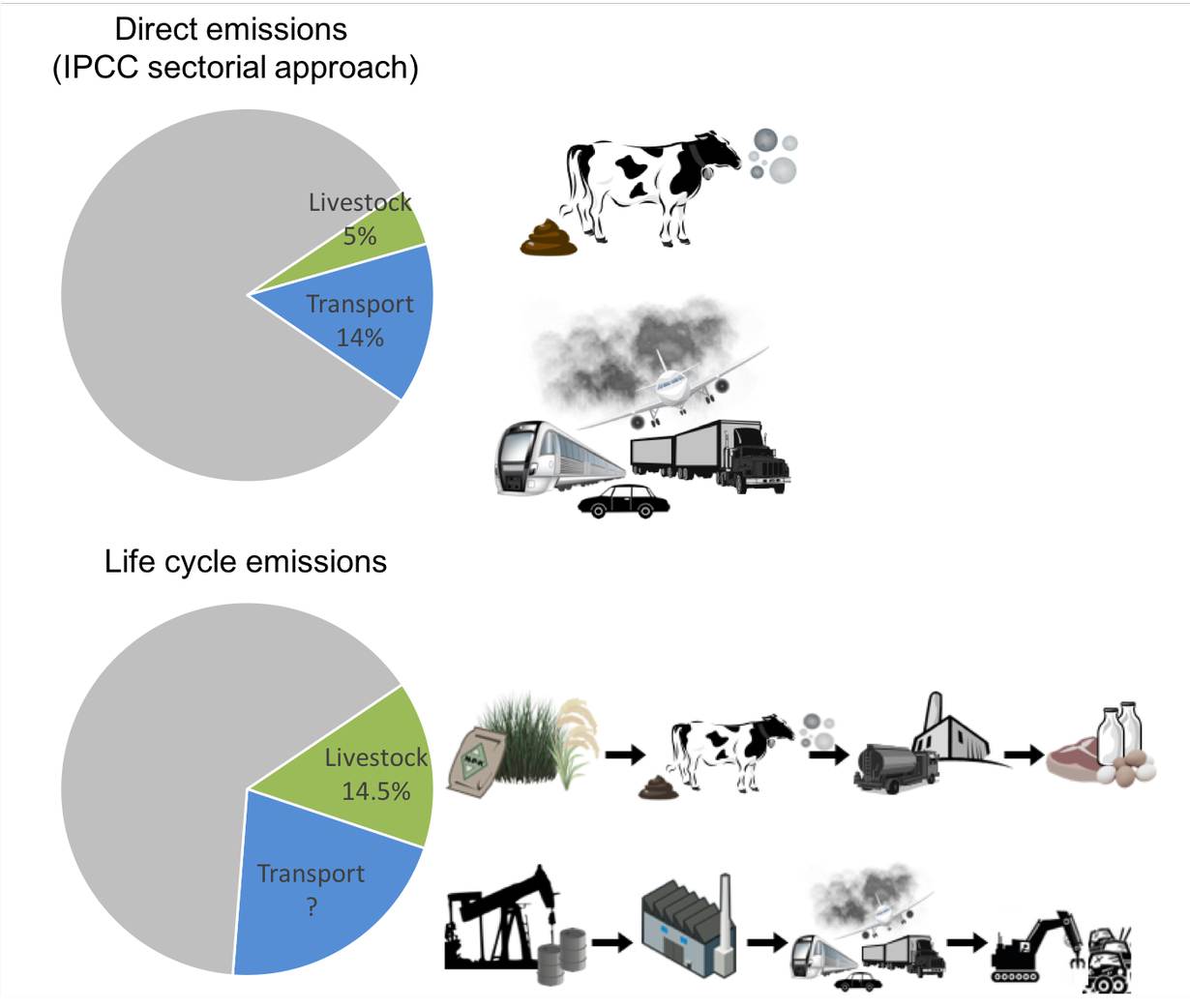

The comparison measures direct emissions from transport against both direct and indirect emissions from livestock. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) identifies and monitors human activities responsible for climate change and reports direct emissions by sectors. The IPCC estimates that direct emissions from transport (road, air, rail and maritime) account for 6.9 gigatons per year, about 14% of all emissions from human activities. These emissions mainly consist of carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide from fuel combustion. By comparison, direct emissions from livestock account for 2.3 gigatons of CO2 equivalent, or 5% of the total. They consist of methane and nitrous oxide from rumen digestion and manure management. Contrary to transport, agriculture is based on a large variety of natural processes that emit (or leak) methane, nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide from multiple sources. While it is possible to “de-carbonize” transport, emissions from land use and agriculture are much more difficult to measure and control.

Using a global life cycle approach, FAO estimated all direct and indirect emissions from livestock (cattle, buffaloes, goat, sheep, pigs and poultry) at 7.1 gigatons of CO2 equivalent per year, or 14.5% of all anthropogenic emissions reported by the IPCC. In addition to rumen digestion and manure, life cycle emissions also include those from producing feed and forages, which the IPCC reports under crops and forestry, and those from processing and transporting meat, milk and eggs, which the IPCC reports under industry and transport. Hence, we cannot compare the transport sector’s 14% as calculated by the IPCC, to the 14.5% of livestock using the life cycle approach.

Though it is the most systematic and comprehensive method for assessing environmental impacts according to the IPCC, there is no life cycle approach estimate available for the transport sector at a global level to our knowledge. Non-availability, uncertainty or variability of data limit its application. But several studies, including some reported by the IPCC, show that transport emissions increase significantly when considering the entire life cycle of fuel and vehicles, including emissions from extracting fuel and disposing of old vehicles. For example in the US, greenhouse gas emissions for the life cycle of passenger transport would be about 1.5 times higher than the operational ones.

Comparing transport and livestock raises another issue. Wealthy consumers, in both high and low income countries, who are rightly concerned about their individual carbon footprint, have options like driving less or choosing low carbon food. However, more than 820 million people are suffering from hunger and even more from nutrient deficiencies. Meat, milk and eggs are much sought after to address malnutrition. Out of the 767 million people living in extreme poverty, about half of them are pastoralists, smallholders or workers relying on livestock for food and livelihoods. The flawed comparison and negative press about livestock may influence development plans and investments and further increase their food insecurity.

Livestock emissions have come into particular focus because it generally takes more resources to produce beef than comparable other food items. Hence emissions from land-use change and feed production are high, in addition to enteric fermentation. Moreover, methane has a higher global warming potential than carbon dioxide but it’s lifespan in the atmosphere is only 12 years, which means that reducing methane emissions would have a positive impact on climate change in a much shorter time span.

Countries, particularly in Latin America, are responding to these challenges by developing low carbon livestock production that will achieve emission reductions at scale, focusing on emission intensity, soil carbon and pasture restoration, and better recycling of by-products and waste. Such programmes also produce a number of environmental and socio-economic co-benefits, like biodiversity and water conservation, or generation of rural employment and income.

The world needs both consumers that are aware of their food choices and producers and companies that engage in low carbon development. In that process, livestock can indeed make a large contribution to climate change mitigation, food security and sustainable development in general.

Anne Mottet is a Livestock Development Officer with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations in Rome, specialising in natural resource use efficiency and climate change. She has 15 years of work experience in research, quantitative analysis and strategic consulting to the agricultural sector.

Henning Steinfeld is head of the livestock sector analysis and policy branch at the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations in Rome, Italy. He has been working on agricultural and livestock policy for the last 15 years, in particular focusing on environmental issues, poverty and public health protection.