* Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Thomson Reuters Foundation.

To find out, we conducted a survey of 537 Democrats, Republicans, and Independents

The last few days surrounding the Christine Blasey Ford and Brett Kavanaugh testimonies have been a flurry of emotions, speculation, and uncertainty. Judgments of whether or not Kavanaugh is guilty are strong - and divided. Republicans are deeply offended by even the suggestion of a small possibility of guilt. Democrats are disgusted that the smallest possibility of guilt is not enough to halt the nomination process. This striking divide has rippled throughout the country.

The stakes are enormously high and both sides have something to lose. At the same time, we’ve put our faith in our elected officials to make sound and objective judgments. But the striking divide would suggest that our lawmakers, along with the public, are not being objective here.

So we asked the question - just how objective are we?

To find out, we conducted a survey of 537 Democrats, Republicans, and Independents. We asked them whether they think Kavanaugh is guilty of sexual assault and how strong they feel the evidence of his guilt is. Because we expected that evidence is not the only factor influencing perceptions of guilt or innocence, we also asked about some potentially biasing factors: how badly they want a Trump supreme court nominee and Republican seats in the midterms, levels of hostile sexism, gender, and other demographic profiles.

We then modeled what predicts whether our respondents felt that Kavanaugh is guilty of sexual assault.

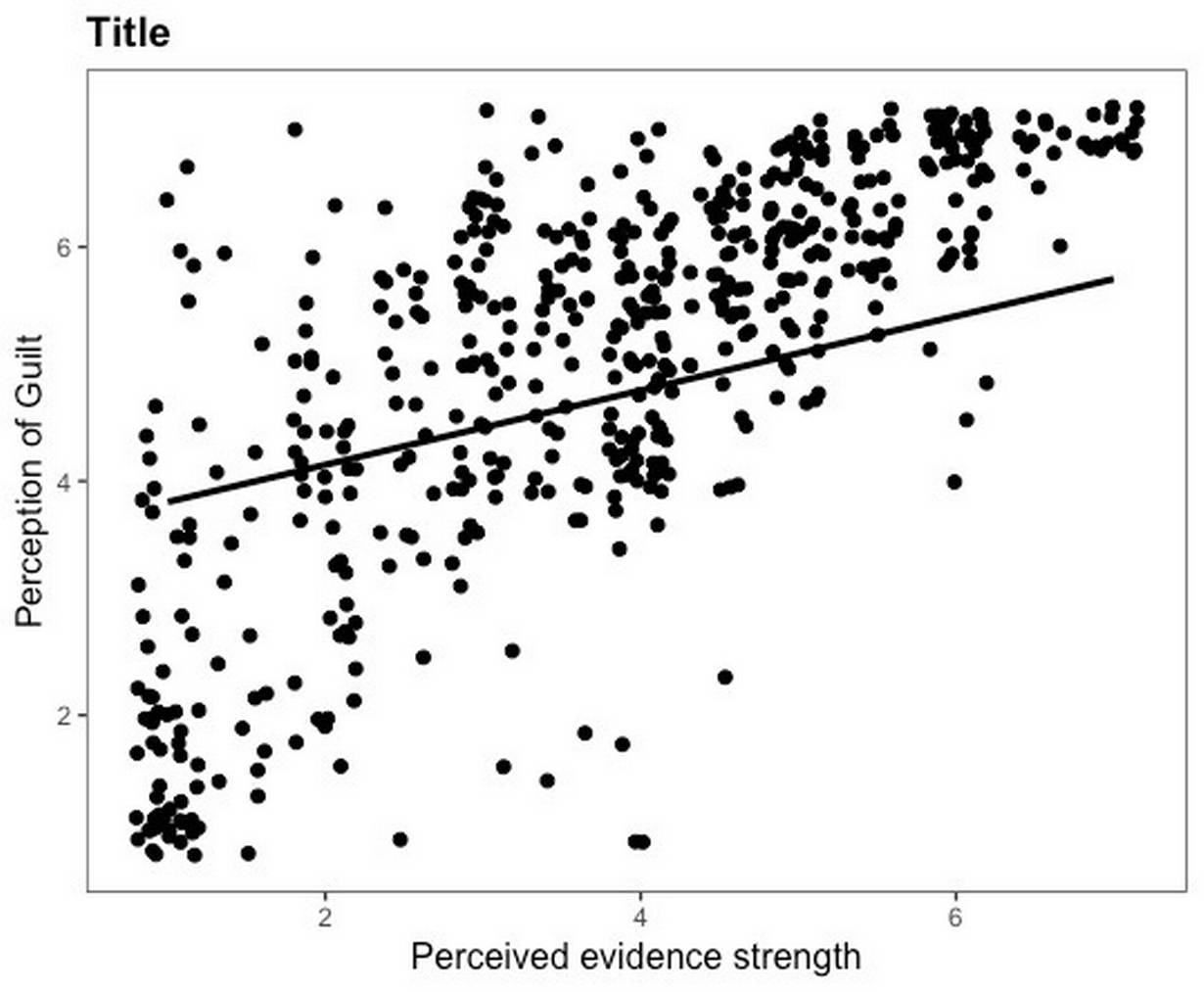

Thankfully, perceptions of the evidence matter to some. People who believe there is strong evidence behind Ford’s accusation also believe that Kavanaugh is more likely to be guilty, and people who feel the evidence is not strong are more likely to think Kavanaugh is innocent.

But perceptions of the evidence are not the only factor influencing whether or not our respondents think Kavanaugh is guilty, pointing directly to non-objective judgments.

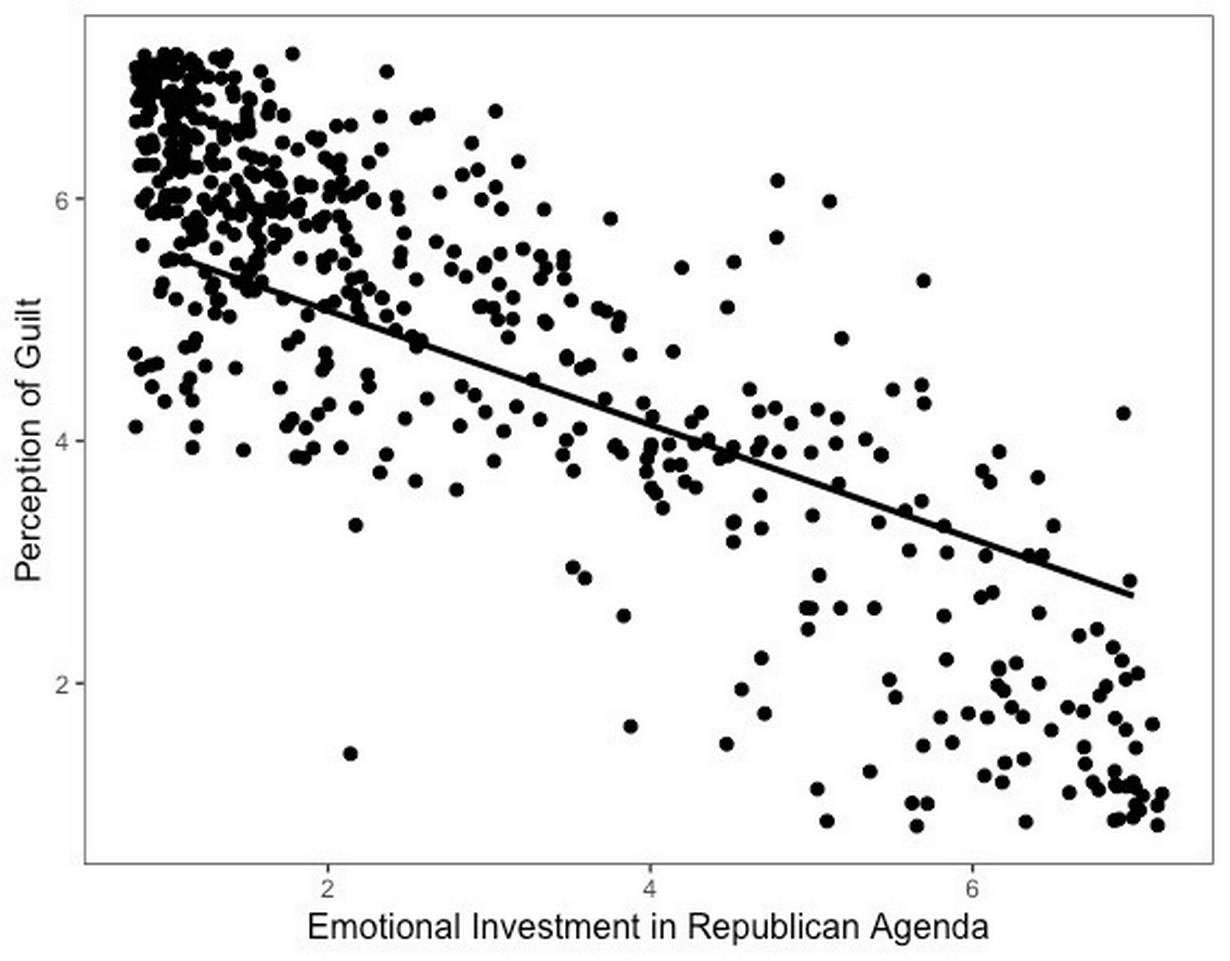

People who are emotionally invested in Republicans succeeding are more likely to think Kavanaugh is innocent. On the flipside, people who are emotionally invested in Democrats succeeding are more likely to think Kavanaugh is guilty. This is controlling for perceptions of evidence, demographics, and hostile sexism (which also predicts perceptions of guilt).

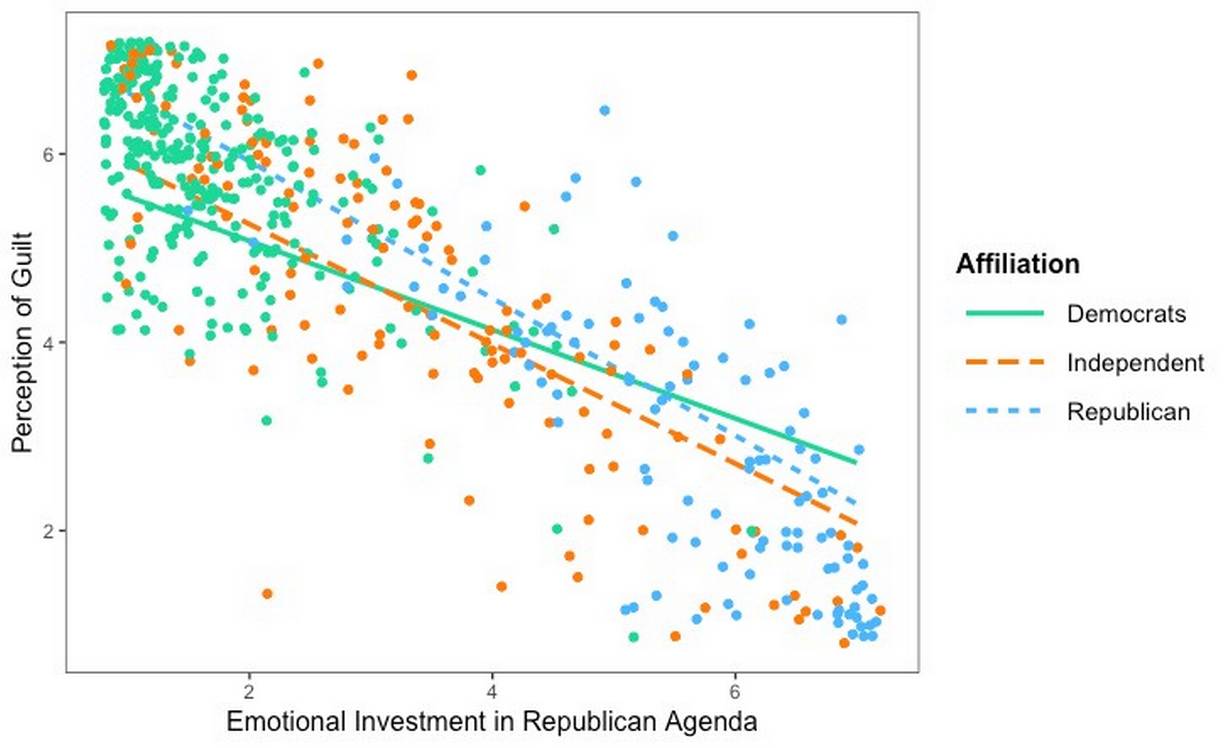

Digging deeper, we see that there are some differences in objectivity based on political affiliation. For Republicans and Independents, the association between a desire for Republican success and perceptions of Kavanaugh’s innocence is even stronger than it is for Democrats.

The data is clear: we are certainly not objective when we make decisions about whether Kavanaugh is guilty. But if we cannot remain objective in these judgments, we risk nominating the wrong person to the supreme court (now or in the future). We risk sending a message to survivors of sexual assault that the evidence alone is not enough if they want justice or healing.

Social science points to a few things that can help us be more objective:

-Openly articulate our biases and think through how they may influence judgments. No one wants to be biased, but we’ve all internalized the beliefs expressed in our society and culture. Be modeled about your biases so you can spot them when they shape your judgments.

-Affirm personal standards of objectivity. Remind yourself why it’s so important to be objective - how it matters both to you and to others in society.

-Create accountability structures. Friends and colleagues can ensure objectivity by pointing out errors or loaded interpretation of the facts. Having to explain your decisions to other people forces you to stand by your judgments.

Finally, let’s not forget the irony of this situation: Our difficulty with objectivity concerns the position with the highest moral authority and impartiality in our entire democratic system. If we cannot be objective when it comes to the supreme court, then when can we be objective?

It is the responsibility of our lawmakers, and of the public, to take the evidence at hand, and make a sound objective judgment. The stakes are too high and the supreme court is too important for anything less. We must all to do better.

Julie O’Brien is a principal behavioral scientist at Duke University’s Center for Advanced Hindsight and a co-founder of The Behavior Shop. English Sall is pursuing her Ph.D. In industrial and organizational psychology and is the Co-Founder of Impact thread, a consultancy specializing in organizational and metric development. Jenna Clark is a social psychologist who researches health behaviors and well-being at Duke University’s Center for Advanced Hindsight.