The ramshackle cluster of tents is home to about 200 Venezuelans, some of the millions who have fled the economic and political crisis in their homeland

By Anastasia Moloney

BOGOTA, Oct 24 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - For the past two months, Joanna Teran, a penniless Venezuelan migrant, and her five children have survived in a makeshift tent on a patch of grass behind Bogota's main bus terminal.

But within days, they will have to leave what has become their home as city authorities aim to shut down Colombia's first and largest migrant camp by the end of this month.

The ramshackle cluster of tents and tarps strung between tree trunks is home to about 200 Venezuelans, some of the millions who have fled the severe economic and political crisis in their homeland.

Neighboring Colombia, and the region, is grappling with the unabating influx. The informal settlement was barricaded by authorities last month to prevent more migrants setting up camp.

Its looming closure leaves migrants like Teran with nowhere to go.

"Even if I have nothing here, no job, no money, it's better than Venezuela," said Teran, who like most migrants crossed the border into Colombia with nothing more than what she could carry.

"At least here, we can eat. Colombians have shown us a lot of generosity and solidarity and bring us food most days," she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Teran, 38, fears her family will be left homeless after their imminent eviction from the camp.

"I can't return to Venezuela. There's nothing there," Teran said, with tears welling up in her eyes.

Teran hopes to save up enough money from selling sweets in the street to rent a room. But her chances are slim as locals are often not willing to rent to Venezuelans, she said.

"It's hard for any Venezuelan to find a place to rent, but it's harder for me as a single mother with children," she said.

DEEPENING CRISIS

In the streets surrounding the camp, migrants offer wads of Venezuelan bills - made nearly worthless by hyperinflation - to drivers stuck in traffic, hoping to get a few coins in return.

Around bus terminals across Colombia, ragged tents and tarps set up by Venezuelans are an increasingly common sight, as are migrants begging.

About two million Venezuelans have fled their homeland since 2015, one of the largest mass migrations in Latin American history, according to the United Nations.

Colombia has borne the brunt, with about one million Venezuelans already living in the country, and more are expected to arrive.

According to recent estimates by the Colombian government, up to four million Venezuelan migrants could be living in the country by 2021, costing national coffers as much as $9 billion.

Cristina Velez, secretary for social services at the mayor's office in Bogota, said the city plans to resettle about 50 people living in the camp to several church-run shelters, with pregnant women and those with children given priority.

"We're going to vacate the camp and hopefully people will leave voluntarily .. we want this to be a totally calm process," Velez said.

"This is a crisis that's not going to end in two weeks, in three months nor in six months. It's a crisis that's beginning, and one that will last a few years to come ... it's what we have to face and prepare for."

Velez said four community centres that will provide support to Venezuelans are being built, while authorities are mulling over plans to set up a new migrant camp with basic services.

About 6,000 migrant children are attending kindergartens and schools for free in Bogota regardless of their migratory status, Velez added.

ON THE MOVE

Some camp dwellers will likely join the stream of migrants moving southwards, many on foot, to Peru, Ecuador and Brazil.

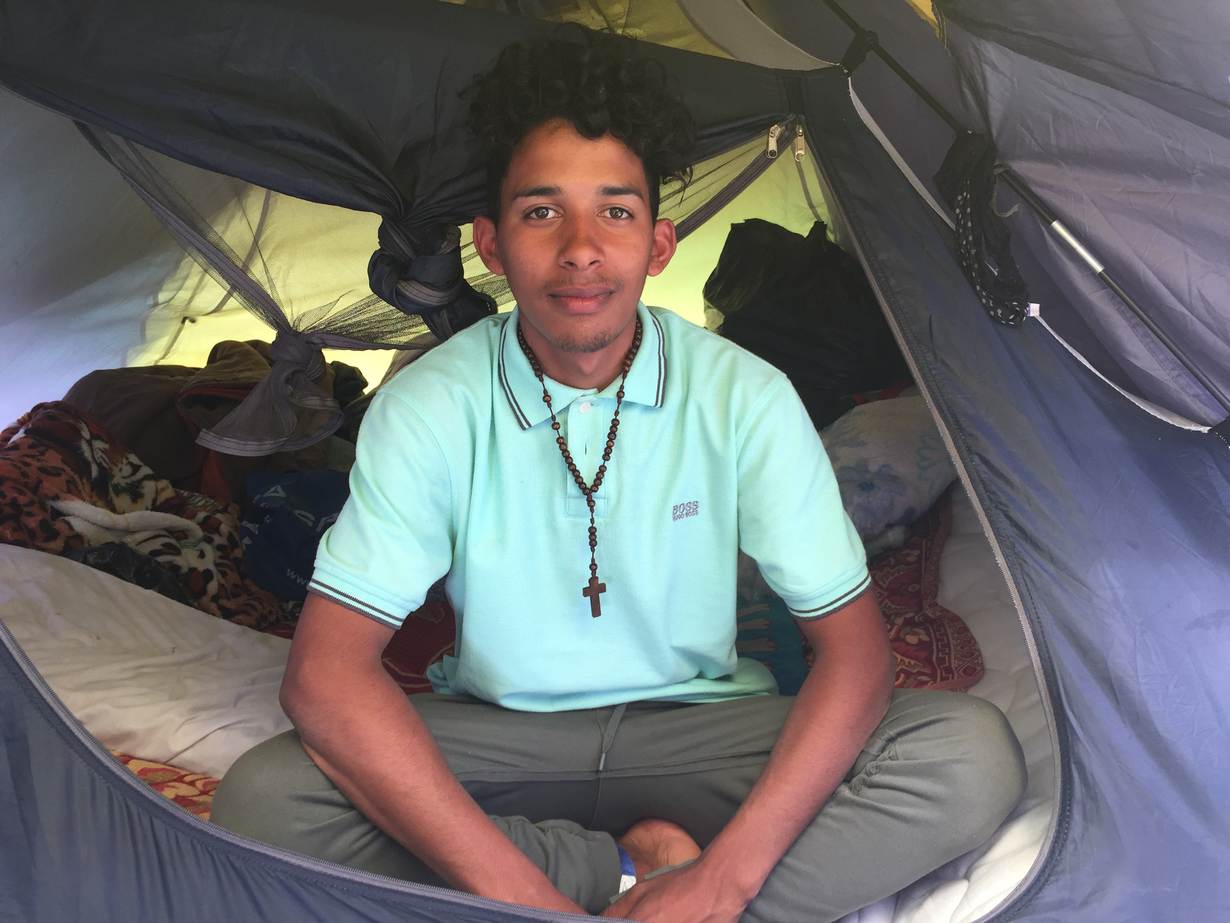

"If we have to move from country to country, we will," said Ronald Pinto, 20, a graphic design graduate who lives with his wife, pregnant with twins, in a donated tent.

Sitting in a nearby tent covered with plastic sheeting to protect from the rain, migrant Giovanni Torrealba says he plans to remain in Bogota but may be living on the street.

A former bodyguard for an opposition politician, he had his left leg amputated after being shot in an attack in 2015.

"If it means surviving on the street, then I will. While I'm not going to put my disability in the way, it's easier for me to stay put," said 38-year-old Torrealba.

"Only when the government in Venezuela falls will I return home," he added.

REGIONAL CRISIS

Other countries in South America are also struggling to cope with the migrant influx as the humanitarian crisis deepens.

A total of about 2.4 million Venezuelans now live abroad - some 7 percent of the country's population.

Affected countries have repeatedly asked for more international aid to help them cope.

In Brazil, which shares a border with Venezuela, social services are increasingly strained as are tensions between locals and migrants.

In August in Brazil's border town of Pacaraima, security forces were sent in after camps of Venezuelans were set ablaze.

In Bogota, stirring a pot of boiling pasta at the camp, Teran said she tries to keep up her hopes despite the looming closing of the camp.

"While I'm healthy, I'll continue and fight. I have to for the future of my children," Teran said.

(Reporting by Anastasia Moloney @anastasiabogota, Editing by Ellen Wulfhorst ((Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers humanitarian news, women's rights, trafficking, property rights, climate change and resilience. Visit http://news.trust.org)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.