Copyright and all photographs taken by Stephen Ferry

-

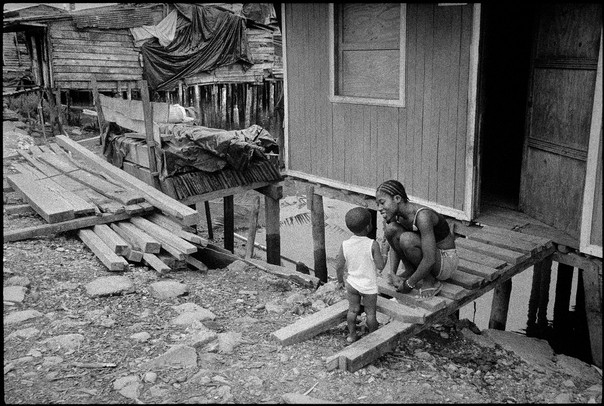

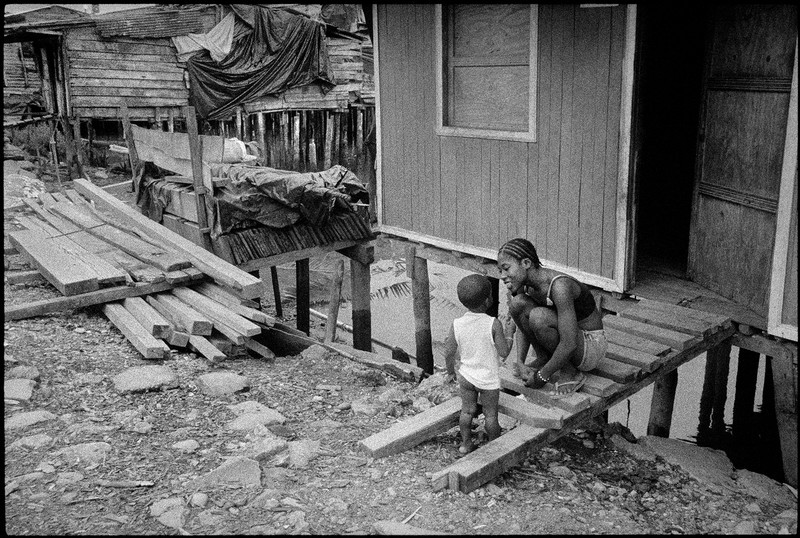

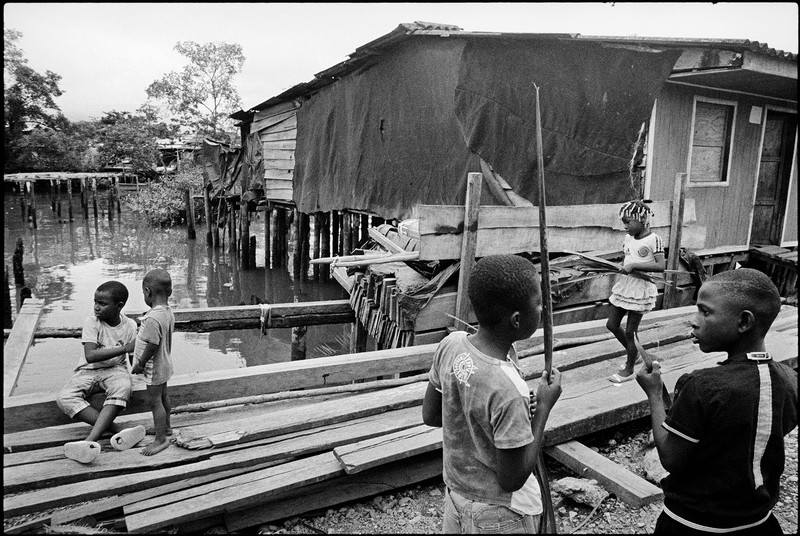

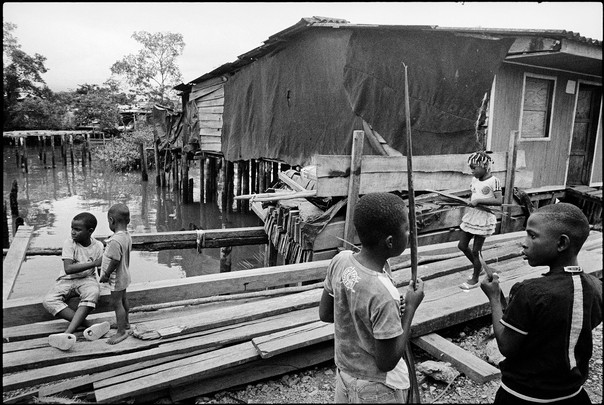

Buenaventura, Colombia’s main port city on its Pacific Coast, sits in the mist of a jungle wilderness.

The location of this steamy city is as much of a curse as it is a blessing. Buenaventura is a gateway to Asia, handling around 60 percent of Colombia’s trade.

But its strategic position also makes Buenaventura a key drug smuggling route for cocaine transported by sea and overland through Central America and Mexico en route to the United States, making it a hotspot for drug traffickers and criminal gangs and one of South America’s most violent cities.

-

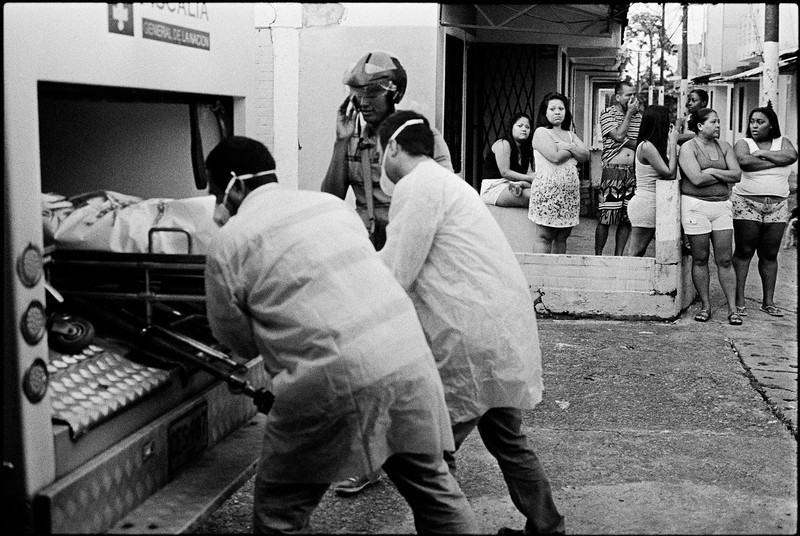

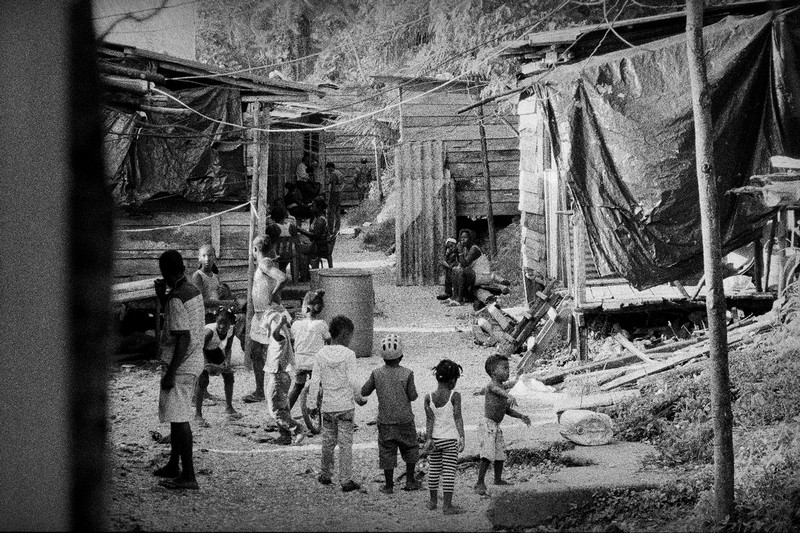

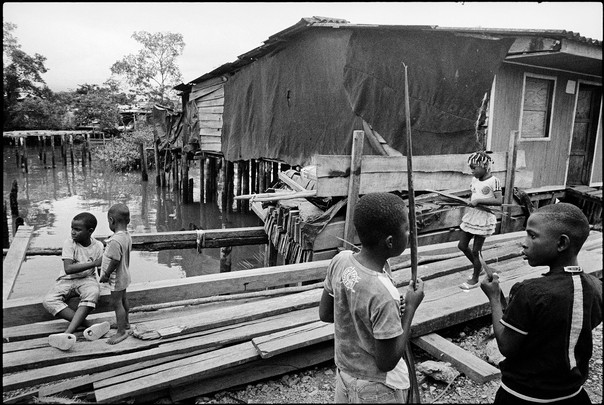

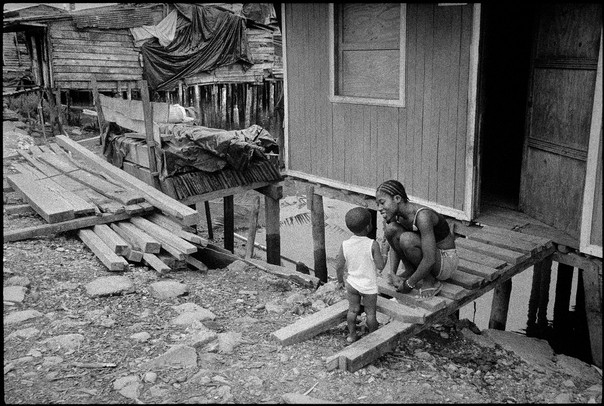

Communities living in waterside slums are often caught in the middle of drug turf wars in a city wracked by ‘terror in no-man’s land’, as Human Rights Watch (HRW) recently described Buenaventura.

Ask any Colombian about Buenaventura and most will say the city is a ‘national shame’.

Colombia is considered a middle-income country and has enjoyed record foreign investment and robust economic growth.

It’s almost impossible, though, to find any of that prosperity trickling down to Buenaventura’s residents.

The city has long had a reputation for lawlessness and high levels of crime.

But the recent wave of violence in Buenaventura has shocked Colombians and dominates local headlines.

Over the past 18 months, the mutilated body parts of at least a dozen people have been found washed up along Buenaventura’s shores, according to Colombian human rights groups, the city’s bishop, Hector Epalza, and testimonies collected by HRW.

Residents have reported hearing people scream and plea for mercy as they are cut up alive with chainsaws in so-called “chop-up houses” by gang members.

-

Colombian authorities blame the latest escalation of violence on a turf war between two rival gangs - the Urabenos and Empresa – as they fight for control over lucrative drug smuggling routes and extortion rackets in Buenaventura.

Slum areas are at the mercy of these criminal gangs linked to former right-wing paramilitaries, who demobilised as part of a controversial peace process from 2003 onwards but then returned to crime.

Anyone who defies their will is threatened and or killed, residents say.

-

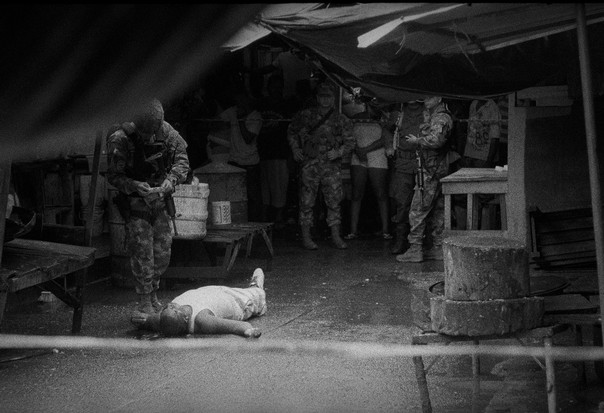

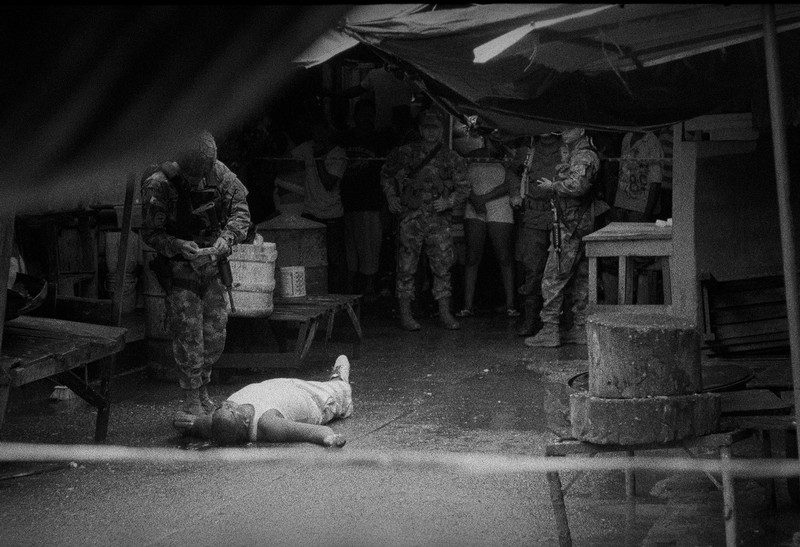

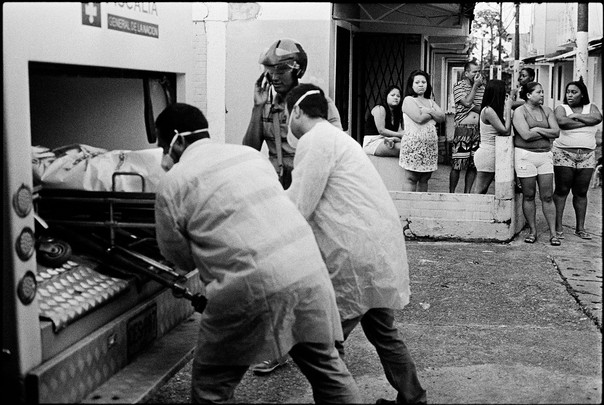

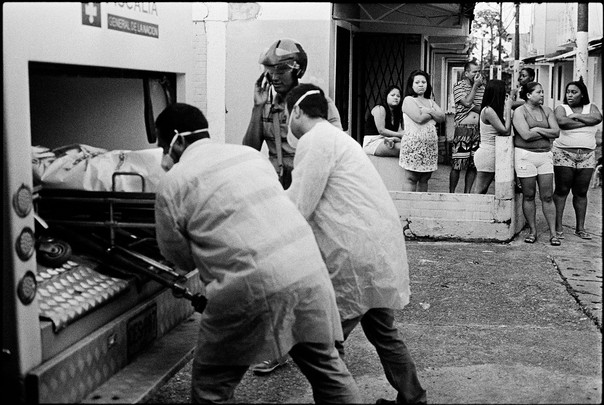

Murders take place every day in Buenaventura.

The city has one of the highest murder rates in South America - at nearly 50 murders per 100,000 people - compared with Colombia’s national average of 31 murders per 100,000 people.

Parents say they fear their children getting caught in gang crossfire and hit by stray bullets.

-

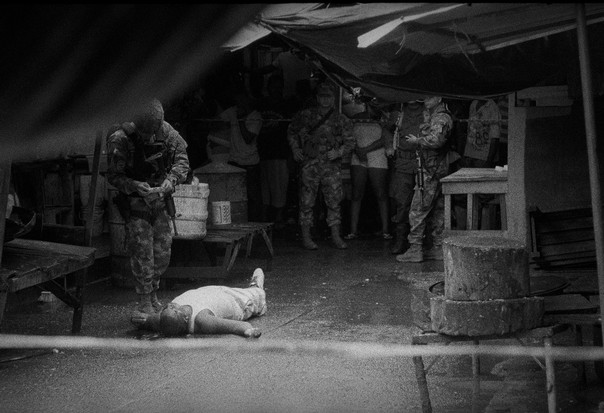

The violence is concentrated in waterfront slums but it also occurs in public places, including Buenaventura’s main market, where this man was shot dead in November 2013.

Residents say they are afraid to be in the street after 6pm because gangs are known to impose unofficial curfews.

-

The violence and fear forced over 13,000 Buenaventura residents to flee their homes last year alone.

The city has reported the highest numbers of residents uprooted from their homes every year since 2011.

Under a scorching sun, scores of displaced people queue at the Catholic Church’s pastoral office every day to receive food, blankets and cooking utensils.

The Colombian government is required by law to provide humanitarian aid to displaced families.

But local authorities in Buenaventura are overstretched and there’s not a refuge for displaced people in the city.

-

Buenaventura is also home to the largest number of people registered missing in Colombia.

This woman in the photograph holds a picture of her son who has disappeared.

At least 150 people have been reported to have gone missing in the city from 2010 to 2013.

-

Some of Colombia's poorest slums are to be found in Buenaventura.

Around 80 percent of the city’s 370,000 residents live in poverty. At least one in four people are jobless here, roughly four times the national rate.

Child malnutrition rates in Buenaventura are one of the highest in Colombia. Most slum neighourhoods have no access to drinking water and toilets.

The United Nations Human Rights Office in Colombia has compared Buenaventura to the Democratic Republic of Congo in terms of its poverty levels and development.

The city’s bishop says violence in Buenaventura is being fuelled by widespread extreme poverty and a lack of jobs.

Decades of neglect by state authorities, the fragile rule of law and corruption between the navy, police and criminal groups are also factors behind the violence, rights groups say.

Buenaventura’s residents say they feel abandoned by the state.

-

In a bid to quell the violence, the Colombian government has deployed 2,400 marines, soldiers and police on to the streets and slums areas. Dozens of gang members have been arrested in recent weeks.

But most residents say sending in more troops doesn’t combat poverty and promote development in the long-term.

Few trust the armed forces and many believe they are part of the problem, accusing them of colluding with criminal gangs and being on their payroll.

-

Women’s rights groups often hold peaceful protests to demand justice and an end to the violence.

During the last big protest in early March, shops and businesses closed for one day and around 7,000 people took to the streets, holding posters saying: “We’re starting to defeat the indifference and “Life is sacred.”