In 2016, Nigeria recorded 2,576 new cases, of which 149 were children, ranking third among African countries with the highest burden of leprosy

By Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani

UZUAKOLI, Nigeria, Oct 27 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - A fter six years of visiting hospitals and traditional healers across Nigeria, 23-year-old Chidinma Mmadubuike finally discovered last year that the baffling sores and lesions dotted across her body were symptoms of leprosy.

By the time Mmadubuike was diagnosed at the Uzuakoli Leprosy Centre in southeast Nigeria, her face was deformed and her husband had driven the young mother out of their home in Lagos and taken custody of their child.

"He was tired of spending money on trying to find out what was wrong with me," she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

One of the oldest known diseases, first mentioned in written records in 600 BC, leprosy still affects millions of people. Between 200,000 and 300,000 new leprosy cases have been detected globally every year since 2005, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

In 2016, Nigeria recorded 2,576 new cases, of which 149 were children, ranking third among African countries with the highest burden of leprosy, after Ethiopia and Democratic Republic of Congo.

Experts are worried that Nigeria could be facing a re-emergence of leprosy, at a time when the global health spotlight and funding focuses on diseases like HIV and malaria.

"The government is no (longer) responding to assist us. Most of the support we get now is from churches and individuals," said Joshua Okpara, project director of the Uzuakoli Leprosy Centre where Mmadubuike is being treated.

"We have new cases on a regular basis. There are (patients) taking treatment. Some others come, take their drugs and go.

TREATABLE

Established by British missionaries in 1933, the Uzuakoli Leprosy Centre has a health unit with wards, and accommodation for those who have been cured but who are unable to return to their homes because of the stigma surrounding the disease.

At the time, leprosy was considered a high risk disease, but advances in medicine mean that it is now completely treatable. If left undiagnosed and untreated, however, it can cause permanent disability.

The Uzuakoli centre has a run-down air, surrounded by overgrown bushes; its hospital wards furnished with bare, worn mattresses. But in the neat residential quarters where the families live, the green-painting buildings are freshly swept, and children play about as the women do laundry.

Between 2000 and 2015, the centre resettled most residents back home, after building flats for each family and helping them find work, cutting the population from about 900 families to 44.

Many of those who remain - the oldest a man in his seventies who lost his fingers and toes to the disease - were abandoned at the centre as children and their families could not be traced.

When leprosy is identified early, it does not lead to deformities or disabilities, but a lack of awareness of the disease and its symptoms often makes diagnosis difficult.

Ironically, experts trace the re-emergence of leprosy to around 1998 when the WHO declared Nigeria had achieved the global health body's target of reducing the proportion of leprosy patients to below one case per 10,000 people.

"So efforts were no longer sustained and people assumed leprosy would die a natural death," said Pius Ogbu, operations manager of The Leprosy Mission Nigeria.

Even experienced doctors sometimes find it difficult to diagnose leprosy, as many of them are not expecting or looking out for the disease when presented with cases.

"There is nowhere we didn't go to find out what was wrong with me," said 32-year-old Okechukwu Moses, a resident of the Uzuakoli centre since finishing his medical treatment in 2016.

Moses' family were convinced that his symptoms, blisters on his feet and a loss of feeling due to nerve damage, were supernatural - that an enemy was targeting their son with witchcraft or juju.

By the time someone suggested it may be leprosy, Moses' big toe was already deformed and his feet were devoid of feeling.

While health workers and civil society are trying to raise awareness, resources and political will are lacking, said Linda Ugwu of the German Leprosy and TB Relief Association, which provides support to the Nigerian ministry of health.

"The commitment to leprosy education is very low," she said.

AWARENESS

The number of families living in the Uzuakoli centre has reduced drastically in recent years, but director Okpara says the task ahead of him is huge, with a new focus on raising awareness of leprosy in communities.

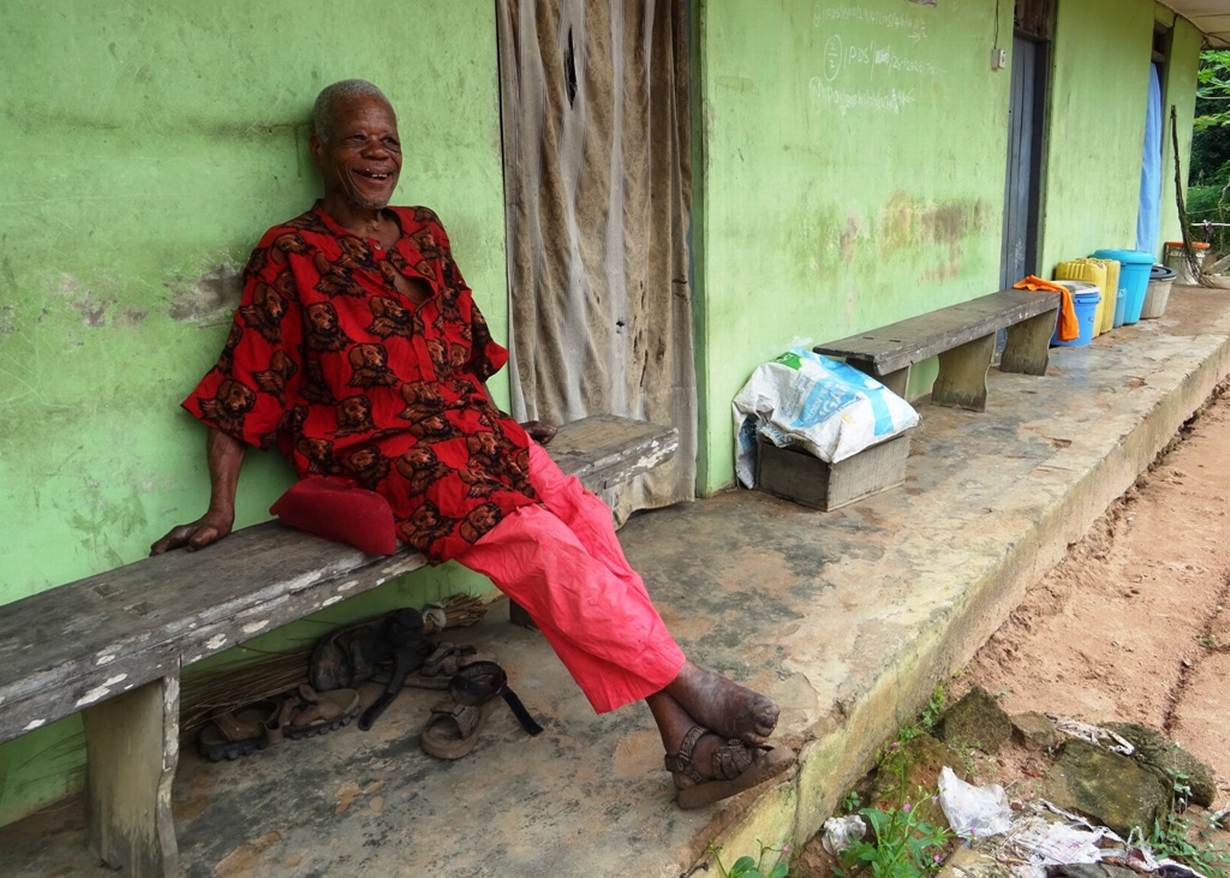

Jenny Eli, 70, has lived here with her daughter, Ijeoma, since 1982 when her husband was diagnosed with leprosy.

Neither mother nor daughter was affected by the disease, but stigma forced them to leave their community. Even after her husband died in 1990, Eli didn't feel safe enough to go home.

"All my children grew up here. I can't go back," she said.

In parts of Nigeria, myths and superstition, and the erroneous perception that the disease is highly infectious, leads to people with leprosy being stigmatised and excluded.

Some former residents of the Uzuakoli centre return after being resettled, begging to be readmitted. Some have lost their homes and had their land taken by their relatives, while many struggle to cope with being shunned in public.

"We've been going to communities to create awareness, meet with community heads, educate them on the disease, encourage them to relate with victims without fear," said Okpara, whose centre has broadcast information about leprosy on radio shows.

Ogbu of The Leprosy Mission said stigma and discrimination around leprosy were a bigger problem than the disease itself.

"To reduce stigma, you need to demystify the disease. Leprosy is just like any other disease. It is curable and the treatment is free," he said.

Thanks to advances in leprosy drugs, there is no need to isolate sufferers, or keep them in centres, health experts say.

"Leprosy centres are not necessary ... sufferers were ostracised because there was no cure," Ugwu of the GLRA said.

At the centre, Mmadubuike expressed relief upon learning that her three-year-old would not necessarily catch leprosy because she had it. She is eager to finish her treatment, and see if she can reclaim custody of her child from her husband.

"He is now with another woman, but if he sees me now, he will be surprised at how much my appearance has improved," she said. "My face looked much worse when I was brought here."

(Reporting By Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani, Editing by Kieran Guilbert and Ros Russell; Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers humanitarian news, women's rights, trafficking, property rights, climate change and resilience. Visit http://news.trust.org)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.