The awakening of Kilauea volcano on the U.S. island of Hawaii was a stark reminder of the destruction eruptions can cause

By Gregory Scruggs

VANCOUVER, Washington, Oct 2 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - On a clear day, scientists at the Cascades Volcano Observatory can see the dimpled summit of Mount St. Helens from the rooftop of their base in a suburban office park.

Once a majestic peak, the volcano, about 95 miles (150 km) south of Seattle and 50 miles north of Portland, erupted in an explosion of hot ash in May 1980, spewing debris over a wide area. The deadliest volcanic eruption in U.S. history, it killed 57 people and caused more than $1 billion in damage.

But that disaster happened nearly four decades ago, and with an average of only two eruptions per century among the 13 snow-capped volcanoes strung along the U.S. portion of the Cascade range, the threat has been a low priority for the region's emergency managers.

This May, however, the awakening of Kilauea volcano on the U.S. island of Hawaii was a stark reminder of the destruction eruptions can cause.

With lava bursts of up to 160 feet (49 m) high, it destroyed more than 700 homes and forced 2,000 people to evacuate.

In the aftermath, scientists from the Cascades Volcano Observatory were called in to relieve overworked Hawaiian colleagues who had been in 24/7 disaster mode, monitoring the volcano with drones, remote sensors and helicopters.

The Vancouver scientists are now hoping their mission to Hawaii, where eruptions occur more often, will elevate concern back in Washington, Oregon and California.

"Big eruptions don't happen that frequently," said observatory volcanologist John Ewert, who spent two weeks at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory after Kilauea erupted. "It's going to be outside of most first responders' and emergency managers' experience."

With emergency staff in the Pacific Northwest occupied by annual disasters like summer wildfires and floods in the spring and fall, Ewert sees the observatory, maintained by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), as the region's volcanic conscience.

It convenes regular working groups of local government officials, healthcare providers and first responders to remind them of the volcanic risks in their midst.

"We have the institutional knowledge about the hazards, and what are the considerations government needs to have to deal with these hazards," Ewert told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

LAVA VS. LAHAR

The climate differs considerably between tropical Hawaii, where warm weather allows basalt lava to flow directly down mountains, and the temperate Pacific Northwest, where high-elevation volcanoes are capped with glaciers.

On those peaks, an eruption would create dangerous mudflows known as lahar. While cooler than liquid-hot magma, lahar would pose a threat to buildings along river banks, just as the Hawaiian lava destroyed homes in its path.

Disparities aside, the questions raised by the Kilauea eruption have allowed Cascades Volcano Observatory scientists to extract valuable lessons for the event of a mainland eruption.

After Kilauea blew, forcing the Hawaiian observatory to relocate to a nearby university, subsequent eruptions oozing magma and volcanic ash lasted months, with some mandatory evacuation orders only lifted in September.

In Hawaii, Ewert and his colleagues received real-time training on the kind of scientific information government officials and residents would seek if one of the Cascade volcanoes reawakens.

Questions about the health effects of volcanic ash and gas were common as Hawaiian officials weighed messages for the public.

Water and electric utilities wanted to know if the plumes of fine ash would affect water quality, and how they might interfere with transmission lines.

COORDINATING CHAOS

By the time, Brian Terbush, a Washington State emergency manager, arrived in Hawaii in June, they had "a well-oiled machine going".

"But they were able to tell me there had been an evolution of that process, and it had been pretty chaotic when it first started," he said by telephone from Camp Murray, Washington's emergency response headquarters.

Terbush witnessed the importance of daily briefings with consistent flows of information, from the Red Cross updating the number of people in shelters to the Environmental Protection Agency reporting on air-quality monitoring.

"We're trying to set up ahead of time who is providing what information and what form it's going to come in - that's going to help us be a little bit less chaotic," he said.

Liz Westby, a geologist at the Cascades observatory, spent three weeks assisting the Kilauea effort in June and July.

She was struck by how quickly topographical assumptions that the volcano would not affect certain neighbourhoods were overturned as lava veered off-course.

In one dramatic moment captured on camera, a drone surveying lava flow doubled as an emergency beacon, as a search and rescue team instructed an evacuee to follow the drone overhead through vegetation and out to the nearest road.

"The speed at which people were being told, 'By Friday, you need to evacuate', and the next week, the homes were gone," Westby told the Thomson Reuters Foundation. "That hit home - the spread of what can happen quickly."

Westby's Hawaiian experience led her to see with fresh eyes the threat posed by Mount Rainier, the tallest Cascade volcano, which last erupted in 1895.

Visible from Seattle on clear days, about 80,000 people live in its hazard path for lahar flow, according to the USGS.

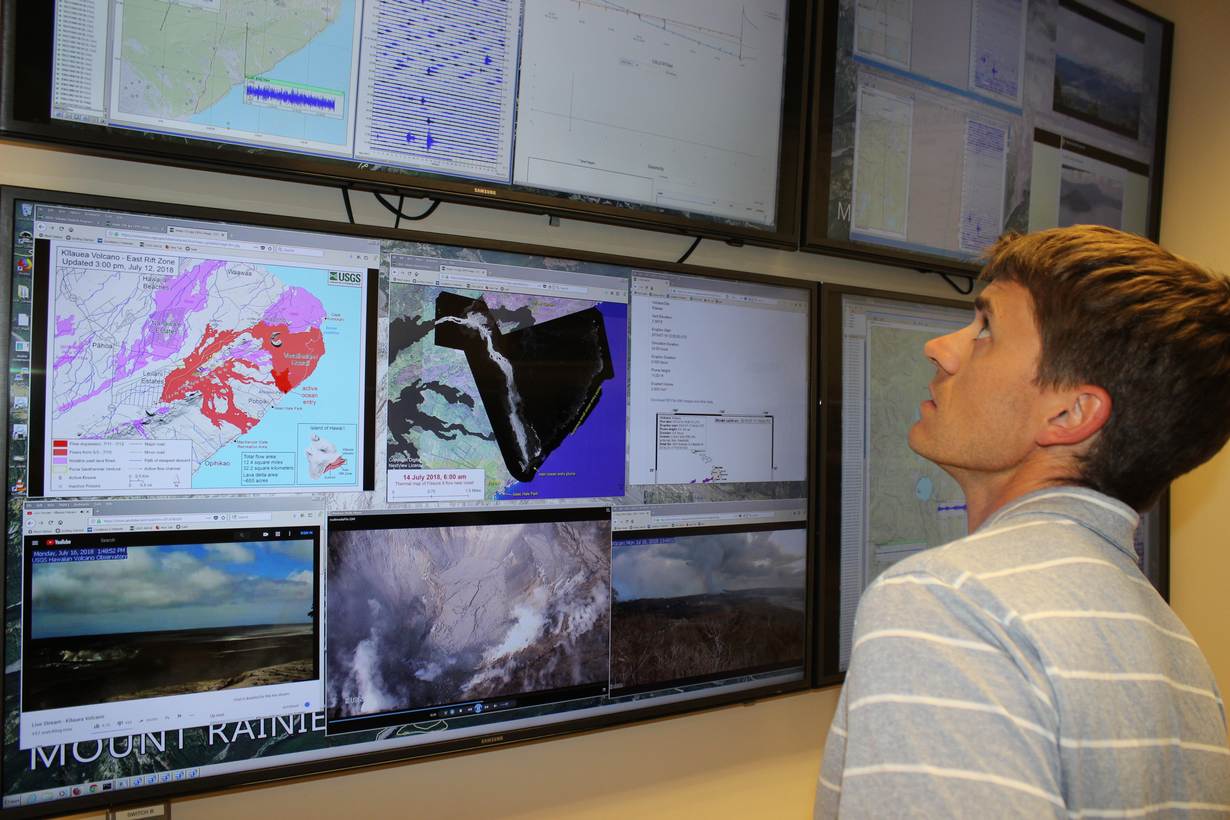

Scientists have installed a lahar detection system that would trigger warning alarms, while staff monitor the mountain remotely from a high-tech control room inside the observatory.

But no one alive today was present during the picturesque peak's last eruption in the late 19th century.

"You just always wonder, will that be enough?" Westby said. "When people hear the sirens, will they act on it?"

For Terbush too, the overwhelming power of the Hawaii volcano was eye-opening.

In other disasters, he said, the priority is preservation of life, then property, then the economy and the environment.

But with a lahar flow, "it's only life safety - you can't preserve that property," he said. "You just have to get out of the way."

(Reporting by Gregory Scruggs; editing by Megan Rowling. Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers humanitarian news, climate change, resilience, women's rights, trafficking and property rights. Visit http://news.trust.org)

The Thomson Reuters Foundation is reporting on resilience as part of its work on zilient.org, an online platform building a global network of people interested in resilience, in partnership with The Rockefeller Foundation.

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.