“The only thing

we know is migration.

Migration equals success.”

Slumped on a bench in a village in southeast Senegal - which is lifeless but for the occasional bleating of goats and splutter of old motorcycles - Aliou Thiam has only one thing on his mind.

The 28-year-old is preparing to leave behind his wife, two children and the only life he has known in the pursuit of a goal shared by many young men across Senegal: reaching Europe.

"I don't have anything here. That is why I want to go, why I need to go," he said, glancing at several men lying nearby in the shade, snoozing through the still, sweltering afternoon.

"The only thing we know is migration," Thiam told the Thomson Reuters Foundation. "Migration equals success."

Thousands of Senegalese men set off for Europe each year, risking their lives on treacherous journeys through the Sahara desert and across the Mediterranean sea. Most fail. Many die.

Senegal is among the top 10 countries of origin for migrants arriving in Italy this year, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) says, along with countries like Eritrea, Mali and Nigeria, beset by conflict or concerns over rights abuses.

But Senegal's young men are not fleeing war. Deemed economic migrants, they are seeking a better life for themselves and their families, and see Europe as the only gateway to success.

It is a belief entrenched over decades as generations of Senegalese moved to Europe - in particular to France, the former colonial master - and sent money home.

But more and more young men are now trying their luck with discontent over joblessness and the slow pace of development simmering in the West African nation.

Despite being one of Africa's most stable and fastest-growing democracies, Senegal's average monthly income is less than $100, and around one in eight people are unemployed.

The surge in migrants has sparked debate globally about whether economic migrants should be treated differently to refugees fleeing conflict, and fuelled fears poverty will worsen and national stability come under threat if remittances dry up.

Uneducated, untrained and unemployed, Thiam and his peers in southeastern Tambacounda, one of Senegal's poorest regions, say they have been abandoned by the government - citing undeveloped land, few jobs, and a lack of vocational training schemes.

"All over Senegal, but especially outside of Dakar, there is a view that you can't make it here, but can make it in Europe," said Jo-Lind Roberts, chief of mission for the IOM in Senegal.

"There is a lack of hope about life in Senegal."

In the heart of Goudiry, young men work tirelessly in wooden shacks, repairing motorbikes, welding steel and sewing clothes.

Yet very few jobs exist outside of the centre of Goudiry, with vast expanses of arid, unused land interrupted only by withered baobab trees and isolated villages.

"To have a job with a salary here in Goudiry is impossible," said 35-year-old Yaya Diallo, who sees migrating to Europe as the only way to feed his wife and children. "I have to go."

Amid thatch-roof huts and mud-brick homes, the few newly-built health centres and schools, and the odd concrete house - some crowned with solar panels and satellite TV dishes - are a testament to the importance of remittances across the region.

"Everything you see is from those who have migrated ... all the projects are financed by them," said Moussa Kebe, who returned to Senegal after almost two years in Libya and set up an association to appeal for development in the area.

"If anyone is sick ... or needs clothes or food ... we have to call on the migrants. When someone passes away, or has to name a baby, we call the migrants - they are always solicited."

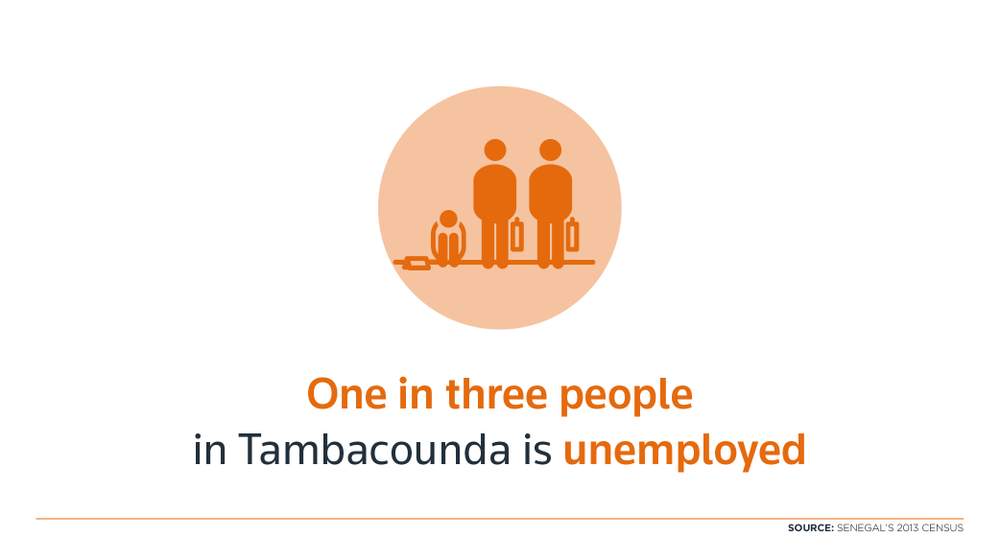

Senegalese migrants sent home at least 930 billion CFA francs ($1.6 billion) in 2015, eclipsing international aid for Senegal and accounting for more than 10 percent of the country's gross domestic product (GDP), World Bank data shows.

This figure may be far higher as it does not account for the cash-stuffed suitcases brought home by migrants, experts say.

Yet remittances to Senegal could shrink as European nations tighten their borders and work becomes harder to find, said Marta Foresti of the UK-based Overseas Development Institute.

Aware of this, the government is working to create more jobs in agriculture, and educate migrants about the risks of migration, said foreign ministry official Serigne Gueye.

"Migration is not the El Dorado people dream of - it is walking into the lion's den," he said in the capital Dakar.

"We want migrants to understand that what interests us is not their lives abroad, but their successful return to Senegal."

The state also backs the Program for Support for Solidarity Initiatives for Development (PAISD), which helps migrants in France to pool their earnings and invest in projects back in Senegal, from solar power systems to mechanic training schools.

"The migrants, with one foot in France and one foot in Senegal, are very important in terms of remittances - they are drivers of development," said Raphael Renault of the PAISD.

But informing people of the risks of migration to persuade them to stay, while relying on remittances to spur development, is an unsustainable strategy, said the Roberts of the IOM.

"Only 20-30 percent of remittances are invested in society, most go straight to families," she said. "You can't just trigger development over a few years - it doesn't work like that."

The success of Goudiry's former migrants, who migrated to Europe several decades ago before returning home to retire, has inspired the younger generations to follow in their footsteps.

Thousands of Senegalese headed to France in the 1960s and early 1970s when booming economic growth saw the country recruit workers from its former colonies for manual labour.

Although France ended its labour migration policy in 1974, former migrants from Goudiry who entered the country illegally afterwards said their journeys were affordable and safe.

But these now elderly trailblazers, most of whom found consistent work allowing them to club together money in order to finance schools, wells and water towers back home, fear that their achievements may have set a dangerous precedent.

"One friend would phone me, telling me that Europe is a thousand times better than Africa."

"Adventure is always difficult, but there were none of today's problems in our time," said 63-year-old Bocar Diallo, who went to Libya in the 1970s and flew to France, where he worked for Renault and an airport during his 33 years there.

But Goudiry's young men are not listening.

Armed with smartphones and televisions - paid for mainly by remittances - they are plugged into social media and TV shows offering a taste of life in Europe too tantalising to resist.

Samba Sidibe, a softly-spoken man in his twenties, said his friends from Goudiry who made it to Europe often phoned him to boast about their new lives in France, Germany and Italy.

"One friend would phone me, telling me that Europe is a thousand times better than Africa," Sidibe said. "I looked on Facebook, I saw the nice pictures - it drove me to go."

Sidibe is one of hundreds of young men in Goudiry who burned through their families' savings to reach Europe, but failed.

More than 1,000 men have left Goudiry for Europe since 2013, said Kebe's Association of Repatriates from Libya. While half succeeded, at least 100 died on the journey and some 350 have been flown home by the IOM and governments of Senegal and Libya.

Repatriated from Libya last year, Sidibe now finds himself worse off than he could have ever imagined.

"I cannot sit here empty-handed," he said glumly, staring at the floor. "I must replace the money (some $2,000) to help my parents get out of this ordeal. If I don't find work, I will be forced to migrate - to try my luck one last time."

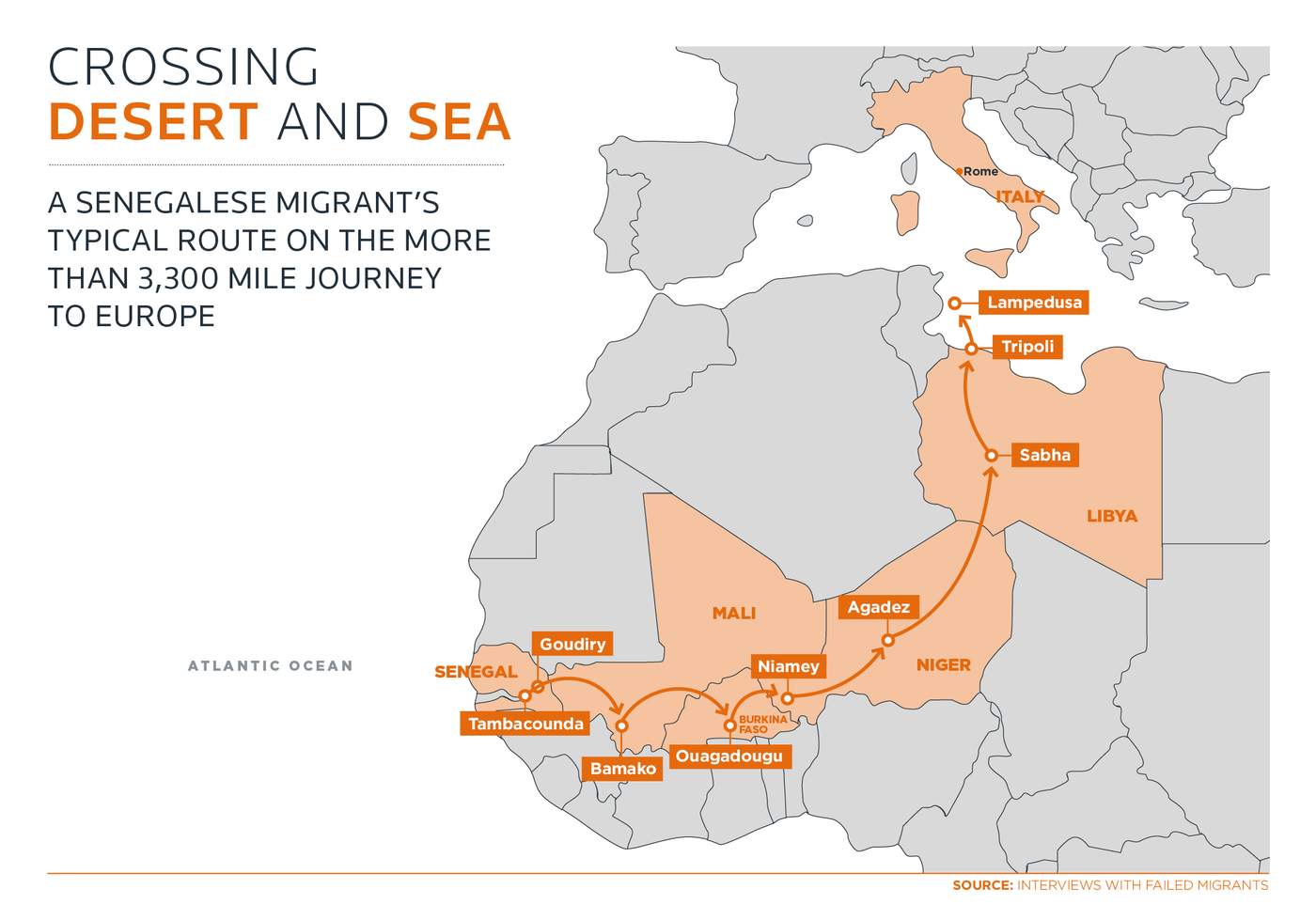

Starting from a bus station in Tambacounda, Goudiry's aspiring migrants take buses, mini-vans and cars through Mali and Burkina Faso to reach Niger's desert town of Agadez - the main transit point in the Sahara for those dreaming of Europe.

For Senegal's young men, among the 300,000 migrants expected by the IOM to pass through Agadez this year, there begins the hellish 1,200 km (750 miles) journey to Sabha in southern Libya – a route prowled by bandits and baked by the fierce desert sun.

"The desert is much, much worse than the Mediterranean or Libya, because it is a place where you have no hope," said Ousmane Thiam, 24, who like Kebe, spent some two years in Libya and is spokesman for the Association of Repatriates from Libya.

While images of dead migrants on European shores have caused a global outcry, Africans heading for Europe may be dying in greater numbers in the Sahara than the thousands who have died in the Mediterranean, according to migration tracking group 4mi.

Thiam and other men from Goudiry who crossed the Sahara recalled being wedged into cars with 20 other migrants, having so little water that they had to drink their urine, burying dead bodies along the way, and being beaten and robbed at gunpoint.

"But I didn't have a choice," Thiam said. "If I had gone home, people would say I was scared - that I was not a man."

Despite having endured the gruelling month-long journey from Senegal to Libya, the nightmare had just begun for Samba Thiam.

Thiam was asleep in a hostel for migrants in Libya's capital of Tripoli when the police burst in, arrested the 39-year-old and sent him to a prison where he would spend three months.

"Sometimes they beat us while we prayed ... innocent people were gunned down when they had done nothing wrong," he said.

"If the person leaving could see ahead to what is happening in Libya, he would not leave. But someone who is motivated by a desire to succeed, and help his family, becomes blind to this."

Despite growing awareness of the dangers along the route to Europe, and warnings from failed migrants about what lies ahead, a rising number of Senegalese are attempting the journey.

At least 6,000 Senegalese migrants have reached Italy by sea from Libya so far this year - more than the total for all of 2015, according to the latest available data from the IOM.

Yet for every man who leaves for Europe, there are the families - wives, children and parents - who are left behind.

Mournful and desperate for news from those who have left, these families often rely on support from their communities - having spent their last franc to buy their relative's passage.

Several widows said they could not stop their husbands leaving, and were unaware of the perils of the route ahead.

In Goudiry's remote village of Ainimady, 28-year-old Falmata Diallo watches a group of women gossip and giggle while stitching bright, floral murals to use as blankets and rugs.

Her eyes flood with tears as she relives the moment her husband left, and the agonising silence she has endured since he called a year ago to say his boat was in trouble.

"When he left, my whole body was dead," the mother-of-three said, convulsing with sobs. "I could not say, or do, anything ... nobody could stop him from leaving."

In nearby Lombi Sadio, 74-year-old Samba Anne and his wife have struggled to cope since the their two sons drowned in 2014.

"They left because they didn't have anything ... (but) they were doing everything, providing for the family," Anne said, cradling a photo of his sons, who died in their mid-thirties.

"When I heard about their deaths, I was finished," he added. "I am not a person any more."

As toddlers squabble over a sack of oranges and teenage boys chase a tattered football towards a goal made out of branches, former migrant Issa Thiam argues with his son about his future.

Ibrahim owns a small shop, but with no other opportunities, he wants to move to Europe to improve his family's fortunes.

"I know of the dangers ... but staying here is harder than the road ahead because, when you are here with nothing to eat or drink, it (life) becomes a crisis," the 24-year-old said.

"It is better to die than to be here."

But he will not leave without his father's permission.

"I will slap him or hold him back if I can - I refuse to allow him to go," said 68-year-old Issa. "Senegal can advance and develop, if the young people stay here and work here."

Yet Goudiry's young men see things differently, bemoaning broken dams, the absence of mechanised farming, and a lack of factories, training schemes and development in the area.

As the sun sets in Toumbouguel, with girls gutting fish and women washing rice for the evening meal, Aliou Thiam smiles wryly at the prospect of realising a better life in Senegal.

"It is better to die than to be here," said Thiam. "I have nothing here."

Credits

| Reporting | Kieran Guilbert |

| Editing | Katie Nguyen Ros RussellBelinda Goldsmith |

| Multimedia | Scott Corben Cormac O’BrienLiz Mermin Judite Ferreira |

| Photography | Mikal McAllister |

| Video | Abdoul Aziz Cissé |

Read more stories from the Thomson Reuters Foundation