RUNNING DRY

Facing dry times, rural South Africans rethink water

At the height of the 2015 drought that parched South Africa's eastern KwaZulu-Natal province, Julie Mkhize had to pull carcasses of dead cows from the dried riverbed near her village, after the desperate animals perished seeking water.

Soon people in her rural community were collapsing as well from dehydration, with 10 dying from drought-related illnesses as drinking water ran short, Mkhize said.

In the years since, the village has seen water flows recover. But this year they are beginning to shrink again, producing deep-seated fear in KwaMusi, a village of 4,000 more than two hours' drive northwest of Richard's Bay.

"Cows, donkeys, goats, children, farmers and families are all competing for the same water," said Mkhize, 63, a small-scale vegetable farmer, sitting in the shade of a community produce-packing shelter.

"We live in fear of the drought, every day."

Around the world, stronger El Nino weather patterns and climate change are bringing harsher and more frequent droughts - and already-dry southern Africa has been particularly hard hit.

Water shortages have killed crops, forced farmers to migrate to look for work, hobbled the hydropower dams much of the region depends on for electricity, and threatened the region's rich wildlife as water-holes disappear.

In 2017, South Africa's Cape Town made headlines as its mayor launched a countdown to a feared "Day Zero" when taps were expected to run dry - a crisis averted only by the city making an aggressive push to conserve water.

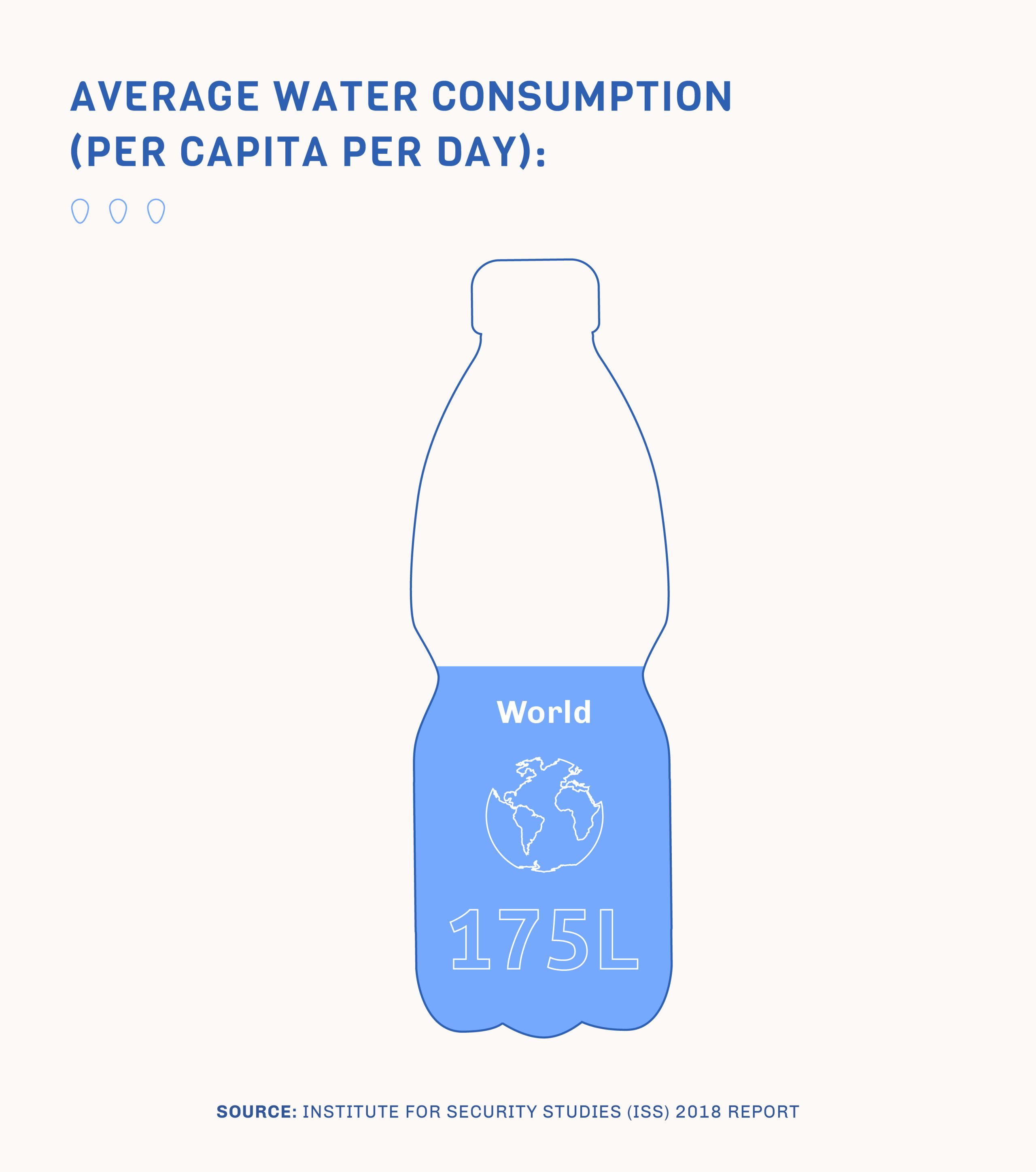

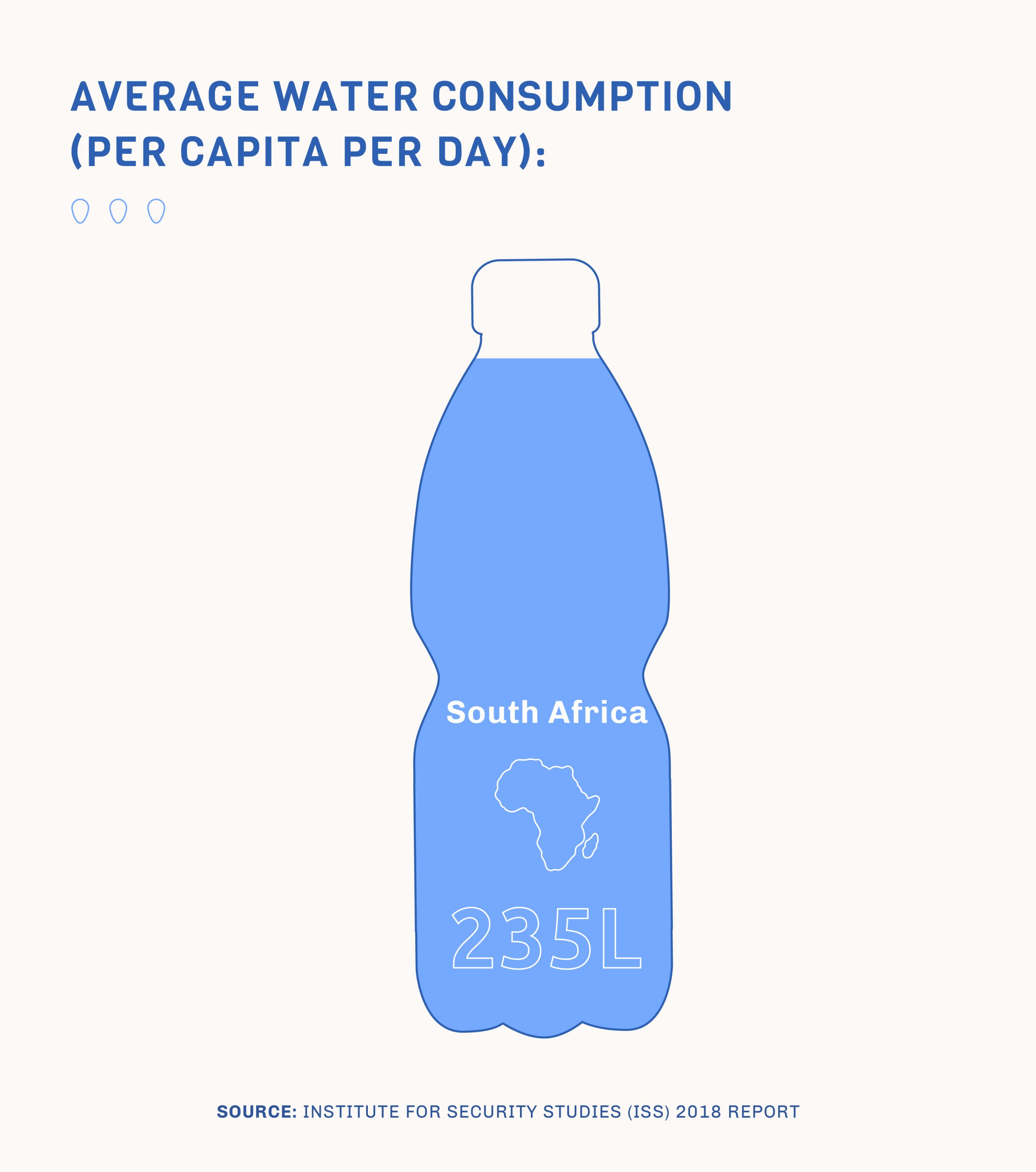

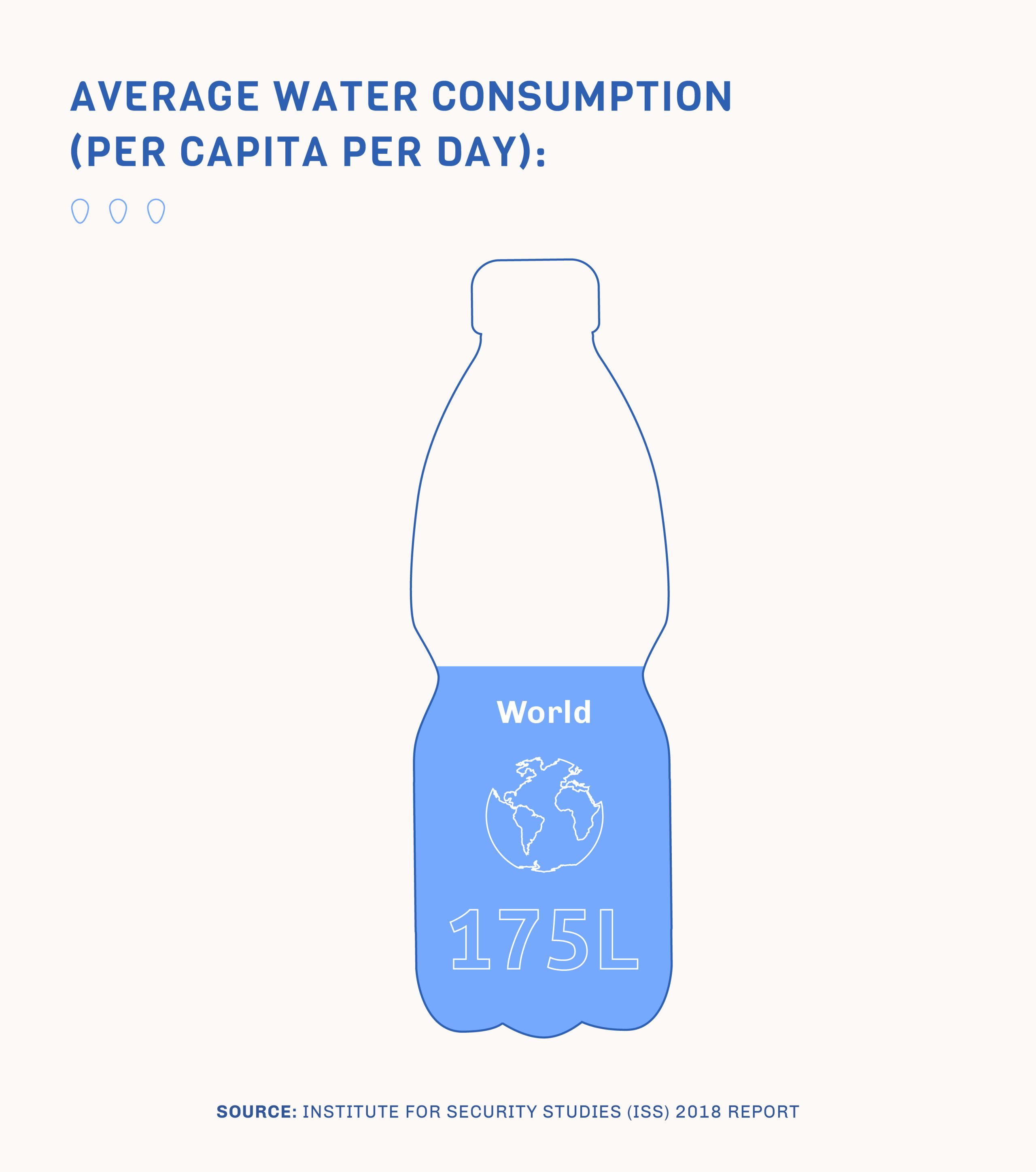

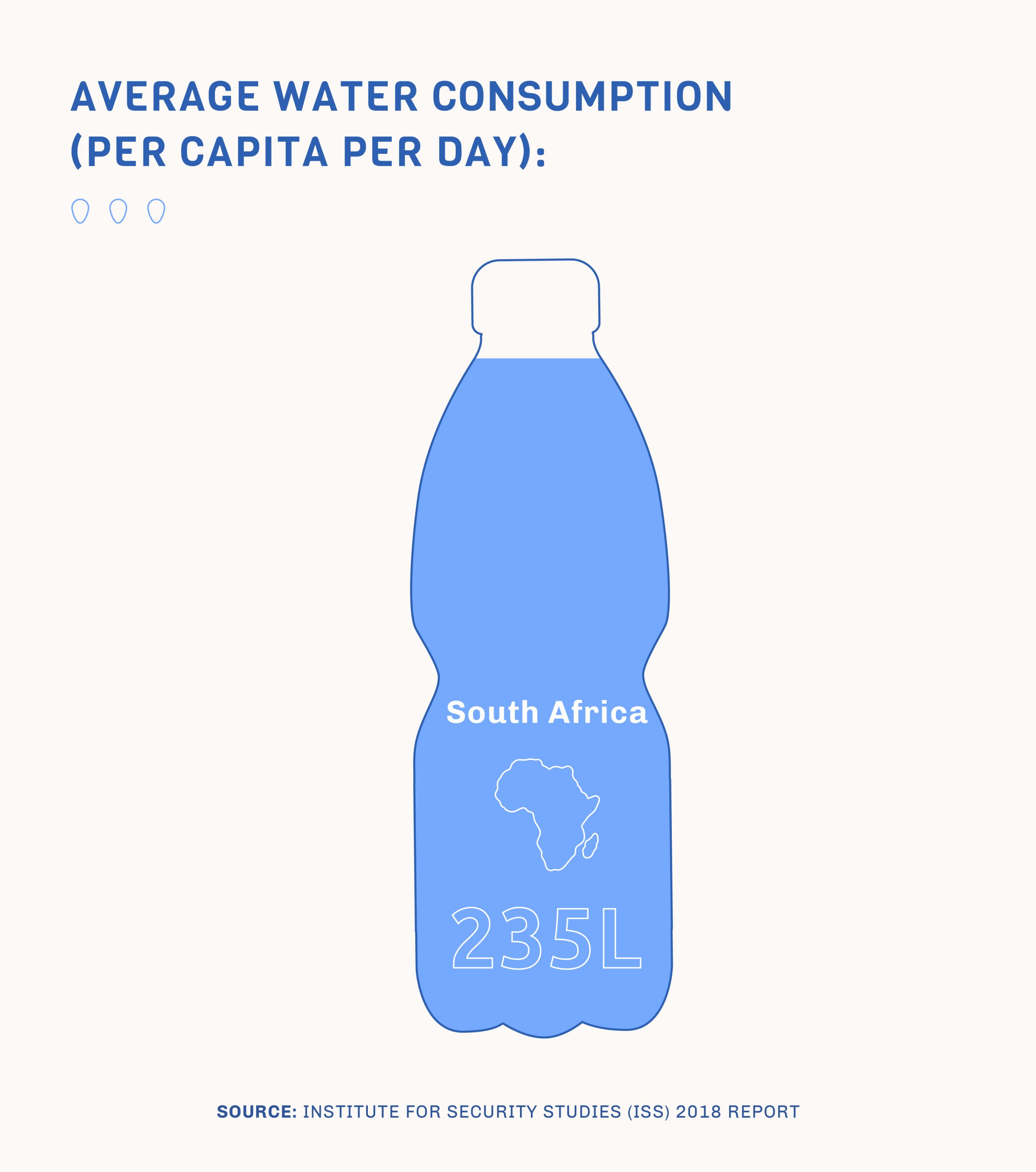

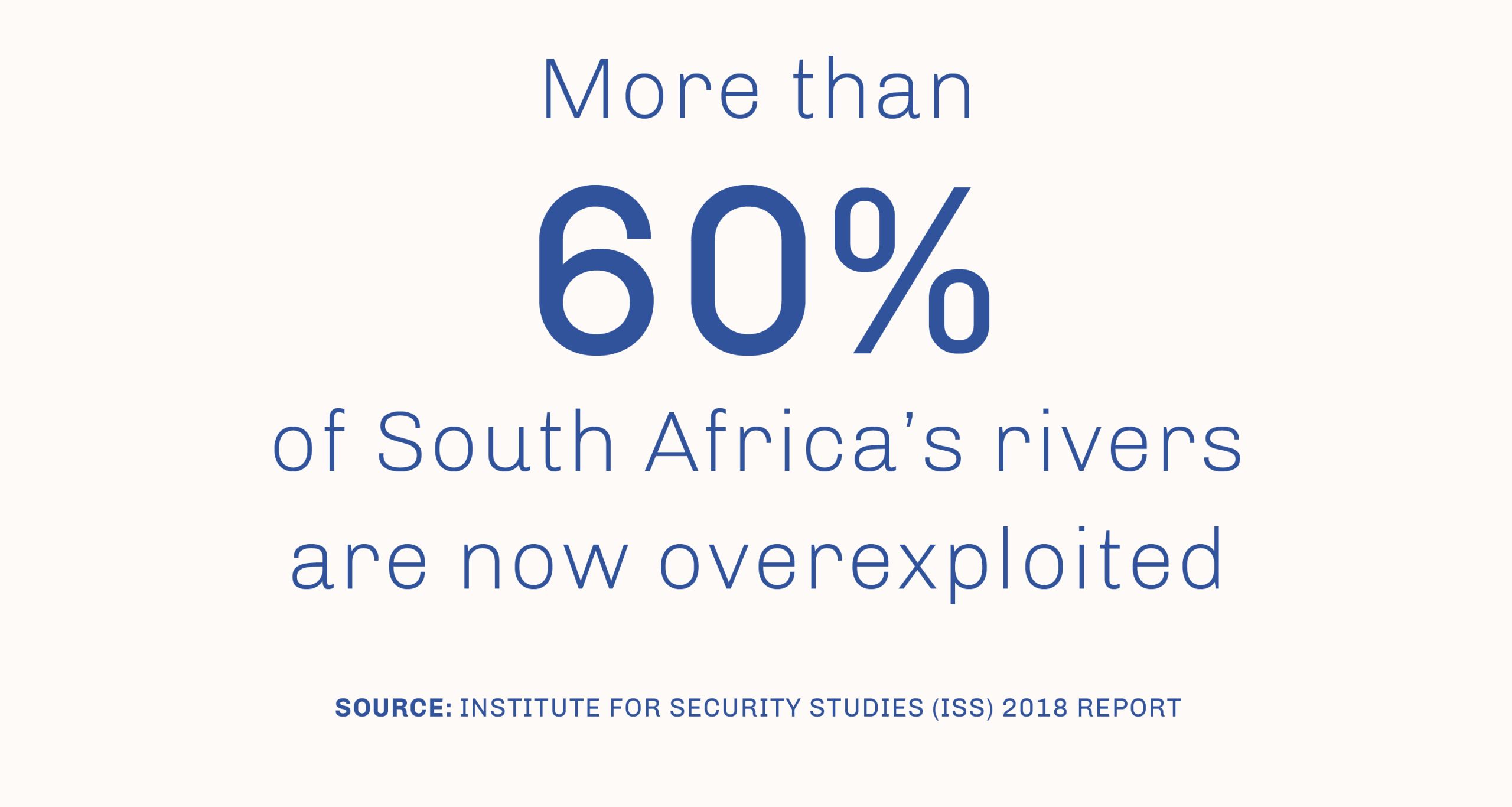

But much of the water-scarce country still suffers from poor water management, according to South Africa's Institute for Security Studies.

Scientists predict that as temperatures continue to rise with global warming and populations keep on growing, the region will see harsher water shortages - and will need to find clever solutions to ensure there is enough water for all.

With supplies scarce, fights over water are on the rise globally, with water think tank the Pacific Institute recording a surge in the number of related conflicts from about 16 in the 1990s to about 73 in just the past five years.

Drip by Drip

In KwaMusi, a drip irrigation system - funded by the Siyazisiza Trust, a non-profit food security group - means Mkhize's vegetable cooperative, the Siza Bantu Nazareth Garden, can now grow and sell crops even through dry periods.

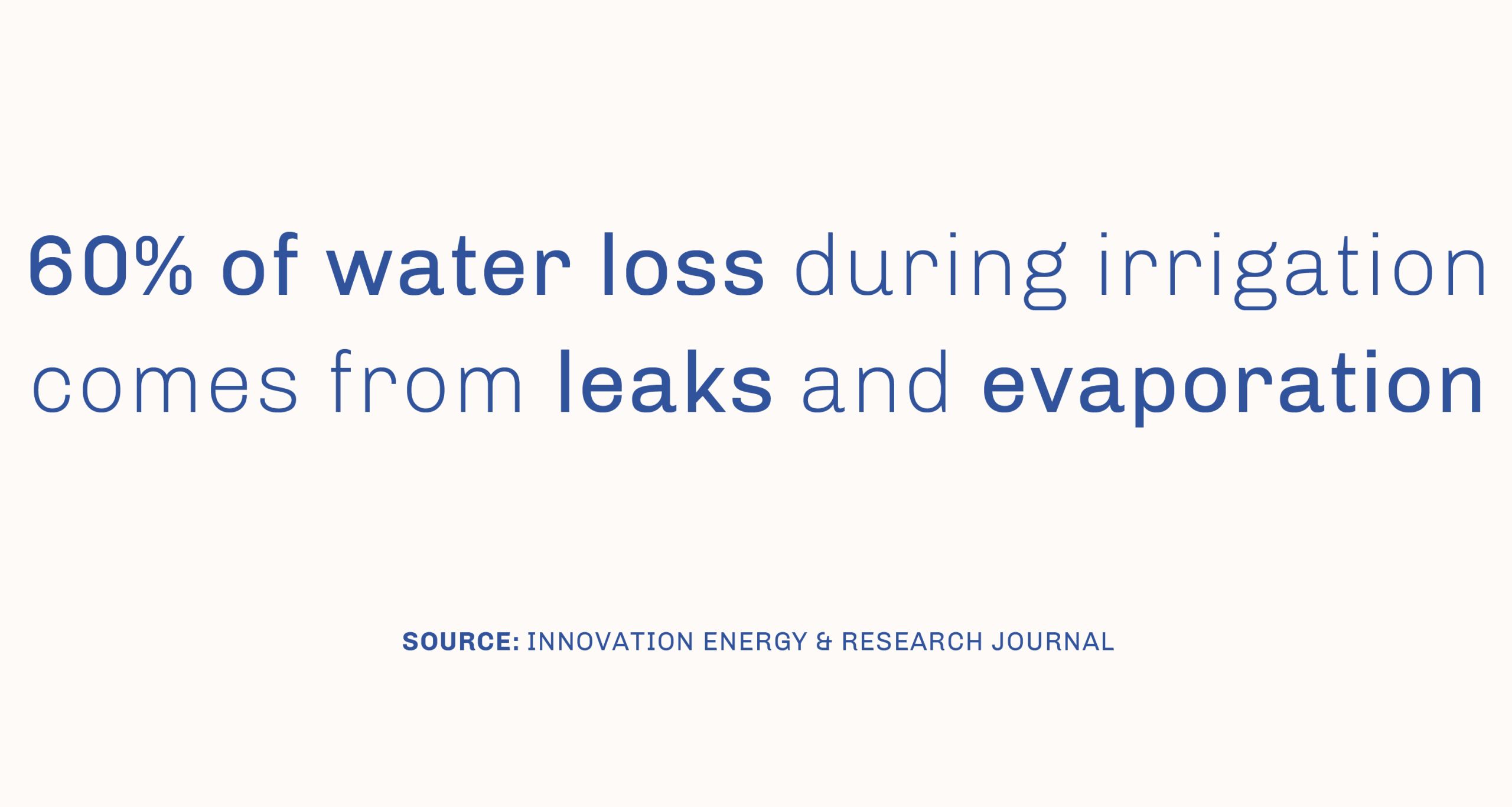

Slim hoses woven through the garden allow river water to slowly drip into plants, minimising losses to evaporation.

Since 2012, KwaZulu-Natal has suffered below-average rainfall, said Phatisa Mfuyo, a spokeswoman at the province's Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Development.

But KwaMusi's hoses have cut the water needed for irrigation and helped the 18 members of the cooperative maintain a steady income of at least 200 rand ($14) per person per day.

That's a huge improvement from 2015, when "we ate mostly cabbage", remembered Lucas Thungo, the only male member.

"We couldn't even eat our staple food of pap (maize porridge) because it required using too much water."

A farmer rests alongside the Mbekamuzi River in KwaMusi, a village in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

A farmer rests alongside the Mbekamuzi River in KwaMusi, a village in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

KwaZulu-Natal's periodic water shortages have sometimes been called a "green drought" because sporadic rains still bring new plant growth.

But the province's rivers - the bigger source of water - are fast being used up, according to a report by the Institute for Security Studies.

"I know it looks beautiful now, but wait until the drought," Thungo said. "Then all you see are rocks and dust. Everything becomes ugly. Even the relationships between different communities change for the worse."

The Next War

About 120 km (75 miles) south of KwaMusi lies the village of Nxamalala, just a few kilometres from the controversial $17 million homestead of disgraced former President Jacob Zuma, accused of using taxpayer funds to pay for the compound.

Residents in Nxamalala say drier conditions are provoking a growing "water war" between adjoining communities.

Farmer Nomathemba Mashange stands among her crops in Nxamalala, a village in KwaZulu-Natal province. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Farmer Nomathemba Mashange stands in front of her crops in Nxamalala village in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, March 31, 2019. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

"Sometimes if you go to a nearby water source, other communities are standing guard at the water. They will beat you if you come near it," said Talent Zuma, 31, who is not related to the former president.

"People say the next war will be over water, but here it feels like it has already begun."

During the 2015 drought, more than 1,000 chickens raised by Zuma's farm cooperative died.

"Eventually the animals start crying out for water. They will either eventually die from walking far distances searching for water, or we will have to sacrifice them," he said.

Community members also remember how the 2015 drought brought itchy skin, fainting spells and, for some, kidney failure and cholera.

Sharing Water

In many rural villages, limited access to water has resulted in near-daily negotiations about how the little available should be shared and used, and how more might be acquired.

In the drought-parched village of Vuna, talks have led to water being trucked in, bath-water being shared - and plenty of thirsty animals.

Zikhuphulile Nkosi, the chairperson of the Kuthelani cooperative, near the river that serves her village of Vuna, in KwaZulu-Natal province. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Zikhuphulile Nkosi, the chairperson of the Kuthelani cooperative, stand next to a river bed lined with badly eroded tree roots in Vuna village in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, March 31, 2019. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

The village's Kuthelani cooperative - the name means Hard Work - sits about 20 km north of KwaMusi, accessible only down a narrow walking path of deep red sand.

The four grandmothers who run the cooperative's one-hectare farm plot, hidden amid thorny acacias and imposing mountains, ululate as Brandon Nthianandham, Siyazisiza's rural community worker, arrives, bearing sugarcane cuttings as a gift.

"This community is probably the most impacted by the drought," Nthianandham said. But regular flash floods on the nearby Vuna River also wash away trees and soil, he said, pointing to a large downed tree on the river's banks.

KwaZulu-Natal province in 1984

KwaZulu-Natal province in 2019

KwaZulu-Natal province in 1984

When rain does not come for long periods, Vuna - like Nkandla - must buy water as both the river and municipal water supply is unreliable, residents said.

"We pay R800 ($55) to buy water from a delivery truck in drier months," said Zikhuphulile Nkosi, 76, the Vuna cooperative chairwoman. "This usually lasts for one month, and then we resort to drinking river water."

But buying water tends to be a last resort as it is an expense most cannot afford, she said.

Zikhuphulile Nkosi, the chairperson of the Kuthelani cooperative, looks at a container that collects rain near the village of Vuna village in rural South Africa. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Zikhuphulile Nkosi, the chairperson of the Kuthelani cooperative, stands by a container containing collected rainwater in Vuna village in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, March 31, 2019. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Instead, the community starts by informally prioritising how limited water supplies will be divided.

"We cherish the government water supply for drinking. For everything else, like bathing, we all move towards the river, which makes it more polluted," said Nkosi. In Nkandla, home to former President Zuma's compound, families are also looking hard at how best to use water.

"First we must cook. We must feed the children," said Nomathemba Mashange, 51, head of the Thelumoyaphansi cooperative in Nkandla.

"Then we will use water to bath. Sometimes two to three of us will use the same water. Then this water is used for irrigating the crops. The livestock become our last priority."

A cow grazes in the KwaMusi village in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

A cow grazes in the KwaMusi village in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, March 31, 2019. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Animals are largely left to fend for themselves, residents say, or slaughtered when they can no longer walk to find water.

In dry periods, when rural people drink more river water, they also suffer diarrhea and cholera regularly from the soap, sewage and animal waste washing down from communities upstream.

"We have all had cholera at some point," Nkosi said.

As government-supplied water arrives only irregularly, "we are forced to drink water we know is contaminated", she said.

Digging Deep

Sometimes even the river runs dry. When that happens, the four grandmothers in Vuna pick up spades and dig into the riverbed to reach water trapped deep in the sand, and insert large plastic containers to collect it.

A plastic cover keeps livestock away."Otherwise the goats and cows will come and drink our precious water," Nkosi said.

Sometimes the grandmothers stand guard, armed with rocks to scare off approaching animals. "Their hooves push the sand back in, filling the river with sand again," Nthianandham said.

When the river is deep enough, the women set up a petrol engine beside it and pump water to their crops, including sweet potatoes that produce good harvests even with little water.

A farmer from Sizabantu cooperative in KwaMusi, rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, smiles as she works. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

A female farmer from Sizabantu cooperative in KwaMusi, rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, smiles in the field, March 31, 2019. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

The soft sand allows the sweet potatoes to expand, yielding large tubers the women can sell in towns, Nthianandham said.

Dried leaves are put on top of the sweet potato seedlings to create a canopy that traps dew and allows the women to farm with less water.

Other communities are trying more drought-resistant crops

The rapidly depleting Mbekamuzi River in KwaMusi in rural KwaZulu-Natal province. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

The rapidly depleting Mbekamuzi River in KwaMusi in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, March 31, 2019. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

In KwaMusi, the community harvests hardy indigenous beans, maize and sugarcane, grown from seeds saved by community members from previous successful harvests, or provided by Siyazisiza.

Other villages are growing amaranth, bulgur wheat and moringa - a plant that contains anti-inflammatory properties similar to tumeric.

Moringa seed - ground with a processing machine - is sold to nearby clinics as a healing supplement for patients.

"These small farming changes mean the community will have something to eat and sell when water becomes more scarce," Nthianandham said.

More wells, more dams

Across rural KwaZulu-Natal, efforts to adapt to drier conditions are evident, from the new 'JoJo' tanks to hold rainwater running off tin roofs to more irrigation pumps and hoses.

For many communities, these innovations are also making life easier, particularly for women.

Before receiving irrigation pumps from Siyazisiza, the women in Vuna carried buckets of water to fields up to 15 times a day.

Farmers pose in front of their rainwater tanks in the village of KwaMusi, in rural KwaZulu-Natal province. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Farmers pose in front of their rainwater tanks in the village of KwaMusi, in rural KwaZulu-Natal province. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

The pump has let them channel their time and the additional water into growing produce and income.

But they fear there is a limit to how much they can adapt to a drier climate if water shortages keep worsening.

"We are hard workers," Nkosi said. "But even if we work hard and plant to full capacity, it will be a waste. The water shortage will mean the death of our produce eventually."

Community members say the government needs to step up and provide more reliable sources of water, especially as river flows become increasingly unpredictable.

"We need boreholes. We need more dams. We need taps," Mkhize said.

Farmers of the Nazareth Sizabantu cooperative show off their water storage tanks in KwaMusi village in rural KwaZulu-Natal province. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Farmers of the Nazareth Sizabantu cooperative show off their water storage tanks in KwaMusi village in rural KwaZulu-Natal province. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

According to Mfuyo, the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Agriculture and Rural Development spokeswoman, the government is working on new water access, and currently deciding on projects for the 2019-2020 financial year.

But villagers remain sceptical that help is on the way.

In February, South African media reported over R220 million ($15.5 million) of national government funds designated for drought relief was missing. A further R120 million was granted.

An investigation into the missing funds is underway, South Africa's Department of Cooperative Governance told the Thomson Reuters Foundation, though a spokesman said the department believes less money is missing than was reported.

Dealing with worsening water scarcity will require South Africans to collectively put "the shoulder to the wheel in order to find solutions", such as rainwater harvesting and recycling water, said Sputnik Ratau, a Department of Water and Sanitation spokesman.

Exposed tree roots and dry sand line the Vuna River, damaged by soil erosion, flash floods and drought. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Exposed tree roots and dry sand line the Vuna River, damaged by soil erosion, flash floods and drought in Vuna village in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, March 31, 2019. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Kim Harrisberg

Kevin Winter, an environmental scientist at the University of Cape Town, said South Africa's government needs to take strong measures to manage ever-more-limited water supplies, and ensure water-related infrastructure works reliably.

"Sadly when water is provided for free in rural areas, it doesn't get properly serviced. What we desperately need is investments in new forms of governance to address matters of water supply and also water quality," Winter said.

Ensuring there is enough water to go around in a drier future will require greater vigilance from everyone, said Lucas Thungo, a community farm worker.

"We need people in power to monitor water usage - both their own and ours," he said. "The 2015 drought was one word: devastating. We simply cannot go through that again."

Credits

Words:

Kim Harrisberg

Multimedia Producer:

Claudio Accheri

Camera:

Kim Harrisberg

Graphic Designer:

Teia Kay

Text Editing:

Laurie Goering, Katy Migiro