* Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Thomson Reuters Foundation.

In one of the world's poorest countries, strengthening climate adaptation could help secure peace

Strengthening the capacity of the Central African Republic to adapt to climate change could help build peace in the landlocked country, which has been hampered by political instability and civil conflict since it achieved independence from France in 1960, research suggests.

Projected estimates indicate that temperatures in Central African Republic could increase by 1.5 to 2.75 degrees Celsius (2.7 to 4.95 degrees Fahrenheit) by 2080, according to a report published in “Climate and Development” by scientists working with the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).

Between 1978 and 2009, temperatures increased in the sub-Saharan African country on average by 0.3 degrees centigrade per decade, while rainfall decreased on average by about 1.9 cm (three-quarters of an inch) per year from 1978 to 2009, the report said, citing statistics from the World Bank.

Developing the ability to adapt to climate change can be a strategic part of the process of reconstruction and reconciliation while playing a central role in meeting development targets, the paper said.

“By building adaptive capacity, you’re really taking care of some of the development issues, and by bringing people together in a genuinely participatory process, you can really contribute to reducing the conflict and tension within the country,” said Denis Sonwa, a scientist and agro-ecologist at CIFOR.

DEVELOPMENT AMID CRISIS

The new research was conducted in Central African Republic, which the United Nations has said is on the verge of becoming a failed state as it struggles with a humanitarian crisis caused by recent civil conflict. It is one of the poorest countries in the world, according to the U.N. Development Programme‘s Human Development Index.

The study, “Institutional perceptions, adaptive capacity and climate change response in a post-conflict country: a case study from Central African Republic”, highlights the ways climate change is affecting the nation of 4.6 million people — in particular the rural poor who form the majority of the population — and identifies barriers to action.

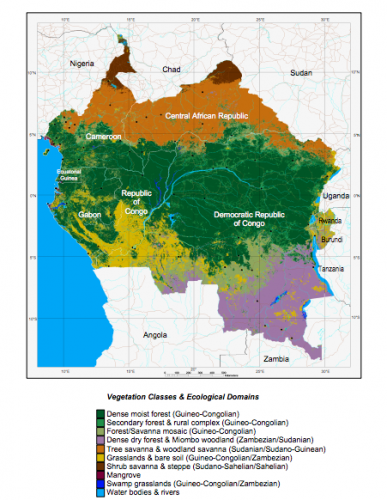

The Central African Republic terrain is covered by a diverse mix of dense evergreen lowland, from the forest of the Congo Basin in the South, to the tree and shrub mosaic forests in the North.

Research interviews conducted in December 2009 with decision-makers from government, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and other key institutions in Central African Republic involved with climate change, development, conservation and forest issues, revealed a high awareness of climate impacts, including changes to the rainy season leading to longer dry spells, said lead author Carolyn Peach Brown, a professor at the University of Prince Edward Island in Charlottetown, the capital of the Canadian province of Prince Edward Island.

However, concrete action to adapt to — or participate in programs to mitigate — climate change was found only to be at an early stage, she said.

“A major barrier to responding to climate change in Central African Republic is the ongoing conflict and insecurity which hampers any poverty reduction or development efforts, including efforts to adapt to climate change,” Peach Brown added.

When people are displaced as refugees, unable to plant crops, get water, sell their goods or provide for their families in other ways, this can only have a negative effect on the population.

The effects of climate change will only make people’s daily lives even more difficult in situations of conflict, she said. Conflict has destroyed infrastructure that was contributing to the development of agriculture in rural areas of the Central African Republic that could have helped improve climate change adaptation, she said.

“The high turnover of personnel in institutions in conflict-affected areas also weakens the capacity of institutions to respond,” Peach Brown added, saying that poor governance, poor coordination across sectors, insufficient engagement with local communities, and inadequate resources for education, research and infrastructure also limits the capacity to address climate change.

According to Sonwa, who co-authored the paper, sharing knowledge and resources among stakeholders is essential to better understand local community needs and build the nation’s capacity to respond to climate threats.

Water availability and agriculture are two key areas of vulnerability in Central African Republic, the research showed. There are two extremes when it comes to water — longer dry spells and an increased prevalence of floods, Sonwa said.

“The agriculture sector is still artisanal — they don’t have irrigation systems — so it is really vulnerable because it is dependent on the rainy season,” he said, referring to the limitations of traditional, low-intensity farming methods.

“And then there is the conflict context, which sharpens that vulnerability. Conflict destroys the networking you have in a community and also destroys infrastructure.”

Conflict also results in missed planting seasons, a difficult situation for rural populations, he said, citing two main activities that have been useful in bringing people to work together: the National Adaptation Program of Action (NAPA), and the REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) initiative.

IDENTIFYING SOLUTIONS

NAPAs provide a process for least-developed countries to identify priority activities that respond to their urgent and immediate needs to adapt to climate change.

REDD+ is a U.N-backed mechanism to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation by offering land managers conditional incentives to keep forests standing.

Both programs were highlighted as key contributors to developing links among institutions. Researchers concluded that these links must be strengthened to build capacity to mitigate climate change, adapt agriculture and natural resource management to long-term trends in climate variability.

Yet, many international organizations have withdrawn from Central African Republic due to instability, which means that the population will not benefit from any of these programs, Peach Brown said.

“The work that local institutions were doing will also not be realized due to the insecurity, but given the realities of climate change for local people, they will still need to deal with and adapt to its effects in their daily lives, even as they are facing insecurity from the armed conflict,” she said.

The research summarized the positive action underway by NGOs in Central African Republic before the latest upsurge in violence, which included work to develop intensive agriculture in savannah and fallow areas to reduce the reliance on shifting cultivation, as well as agroforestry and reforestation projects.

“The agricultural sector needs to be made more resilient — by doing so, you are really helping to rebuild the country’s food security,” Sonwa said.

The research reported that environmental NGOs have been engaged with indigenous groups on forest mapping projects expected to improve forest management related to climate change and REDD+, while universities have been investigating the sensitivity of flora and fauna to change —important considerations for local communities who use the forests as a food source.

And after the conflict? Any ongoing foreign assistance will need to recognize the increased vulnerability of local people due to climate change, as well as the armed conflict, Peach Brown said.

“Following civil conflict, building adaptive capacity to climate change, which fosters linkages among diverse institutions, could also contribute to the process of reconstruction, reconciliation and peace building in a country,” she said.

Sonwa agrees. “It would be difficult to say you’re doing good post-conflict reconstruction, without taking into account the climate,” he said.

For further information on the topics discussed in this article, please contact Denis Sonwa at d.sonwa@cgiar.org

This work forms part of the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry and was conducted under CIFOR’s Congo Basin Forests and Climate Change Adaptation (CoFCCA) project and supported by Climate Change Adaptation in Africa, International Development Research Centre and the UK Department for International Development (DFID) — and a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Postdoctoral Fellowship. It was also supported by the University of Guelph.