As extreme rainfall brings more landslides, farmers are turning to bamboo to protect their land - and making an income from it

By Kagondu Njagi

MAKOMBOKI, Kenya, Nov 7 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - Lunch at Macharia Mirara's house in the village of Makomboki used to be a cheery occasion as his children chattered about their morning at school. But these days, no one is home.

The family is absent because of the threat from an adjacent loose earth slope, which runs about a kilometre down to the valley floor in central Kenya's Murang'a County.

Community leader Zachary Muriu worries the remaining layer of soil left after a landslide in March 2016 could become dislodged at any time.

"The short rainy season has started," said Muriu, explaining why the Miraras had gone to stay with a relative. "The family is afraid a landslide could happen, and sweep them away."

It is a problem that troubles others living on hilly terrain in central Kenya, as rains become heavier and slopes deforested.

But some are trying to protect themselves with a simple technique - planting trees, said Muriu.

"The trick is to plant bamboo along with crops on hilly land and along river banks," he said.

The giant grass prevents soil erosion and is a natural purifier of water flowing into rivers, he added.

Naftali Mungai, an independent conservationist based in Nairobi, said bamboo spreads rapidly when planted, with a single tuber on the mother root able to produce more than 50 offshoots.

The extensive root system enables bamboo to stand firm even on loose soil like that covering Mirara's land.

"It (bamboo) reduces the possibility of soil eroding away during heavy rains, and is able to refine underground water," said Mungai, adding that it grows very fast.

The Miraras have yet to plant bamboo, even after the 2016 landslide swept about three acres (1.2 hectares) of their land downhill.

Their home stands on the edge of the scarred site of the disaster that destroyed part of Mirara's tea plantation and killed one woman, according to Muriu.

Mirara's family were left destitute by the landslide, said Muriu, who also chairs a community conservation group.

TEA TROUBLE

But about 1,000 families in the village have now planted bamboo on their farms.

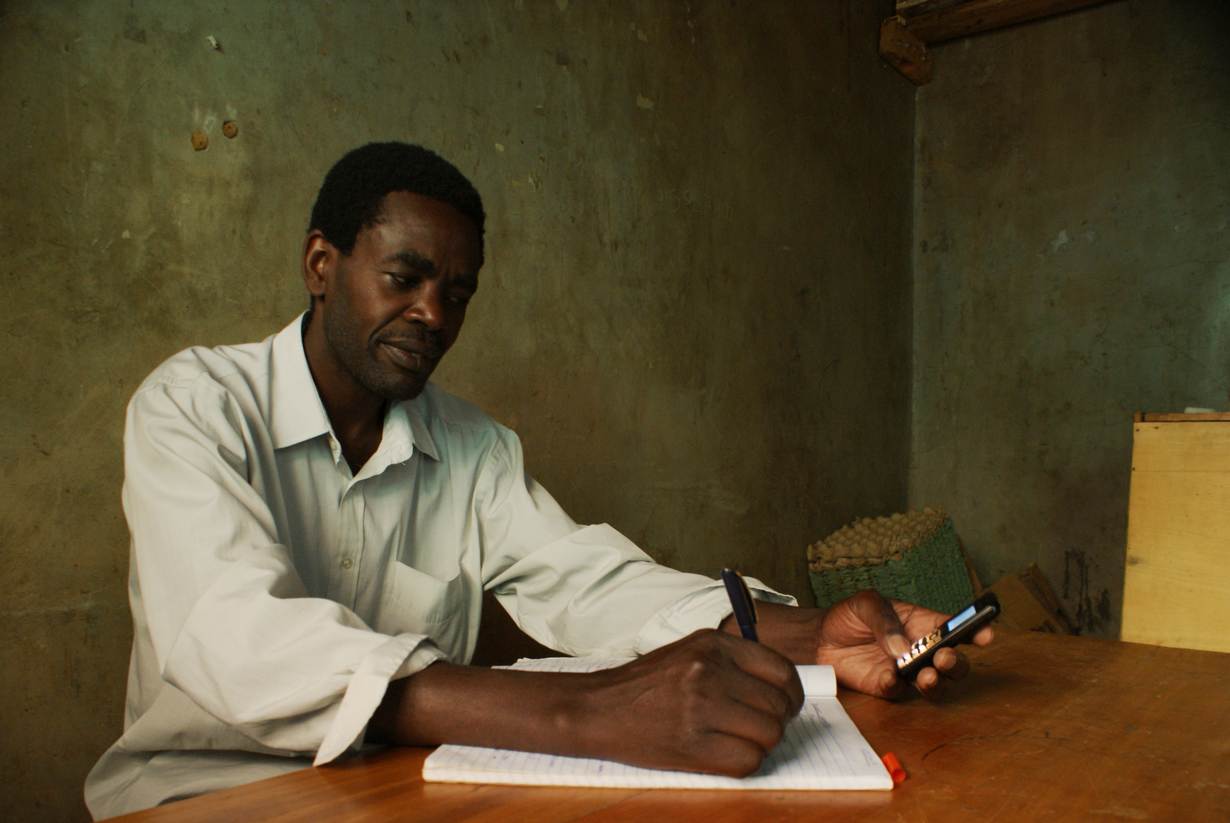

Samuel Karanja, a 47-year-old farmer who also works as a mason in Nairobi, has included the giant grass in a mix of other trees, such as cedar and pine, on his one-acre farm.

Tree-growing is a personal passion for Karanja, but he also sees an economic advantage.

Bamboo can be used to make furniture and fence poles, and even to construct homes, as well as protecting against landslides, he said.

"Bamboo re-grows when it is cut down and does not rot away like other trees when they are felled," said the father of two.

One mother plant can generate annual income of about 100,000 Kenyan shillings ($983), he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Its most important function, however, is to help reforest the area, he said. He blamed tea factories for depleting trees in his area, saying they are cut down and burned to cure tea.

Karanja and other villagers said the high rate of local deforestation worsens the risk of landslides, as fewer trees means soils are less well anchored.

The drainage system for rain water is also poor, Karanja said, explaining that surface runoff usually cuts its own path through farms as it flows downhill.

Francis Wainaina of Kangema FM, a local radio station that provides weather information, said rains had become more intense in central Kenya, influenced in recent years by the El Nino climate pattern, triggering floods, land slips and mudslides.

'NEGLECTED'

Despite the disasters caused by degraded land and inadequate infrastructure, the county government is doing little to help, locals said.

"The leaders only come to comfort victims," said Muriu.

Residents should be trained in first aid, he added, so they can provide the service free to disaster-hit communities.

Murang'a County Governor Francis Mwangi wa Iria said a county fund of 30 million Kenyan shillings had been set up in June to help disaster survivors rebuild homes or relocate.

Assistance was being provided in stages, with the aim of reaching all those who need it, the governor's office said.

At the national level, Kenya established the Constituencies Development Fund in 2003. It supports grassroots projects to improve food and water security, healthcare and other basics.

The fund, which receives 2.5 percent of national revenues, is also meant to empower counties to intervene when communities are struck by disaster, said Francis Chachu Ganya, a member of the Kenyan Parliament's environment and natural resources committee.

Macharia Maguta, a resident of Mareira village in central Kenya, said he had never benefited from the fund.

The father of eight walks with a limp after slipping and dislocating a leg while trying to cross a flooded road.

His appeal for help from local leaders went unanswered, and he is now determined to reach the president to argue his case.

Villagers said inadequate government assistance meant farmers like Karanja must divide their time between paid work in the city and planting trees to protect their land at home, in an effort to keep their families safe from disasters.

"I feel neglected," said Jane Wanjiru, a Kangema resident whose child drowned while crossing a flooded river in 2016.

"The leaders come to ask for votes from us, and we give them. But when there is a landslide or someone drowns due to heavy rains, they are never seen," she said.

($1 = 101.7000 Kenyan shillings)

(Reporting by Kagondu Njagi; editing by Megan Rowling and Laurie Goering. Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers humanitarian news, climate change, resilience, women's rights, trafficking and property rights. Visit http://news.trust.org/climate)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.