* Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Many investors have long appreciated the need to protect the planet. They are uniquely placed to change the world for the better – if they use the right tools.

Laurent Ramsey is the chief executive of Pictet Asset Management and Managing Partner of Pictet Group.

Kanpur in northern India is known as the Manchester of the East. Located on the banks of the Ganges river, it is home to various heavy industries, including leather, chemicals and fertilisers.

But, unlike its English twin, the Indian city’s economic heft brings enormous side-effects. Kanpur has become the world’s most polluted urban centre -- as measured by the World Health Organization. Kanpur’s 3 million inhabitants are breathing in air that is up to five times more polluted than the WHO’s recommended limit.

Kanpur is not an isolated case. According to the WHO, toxic air is estimated to kill at least 9 million and cause economic losses of USD4.6 trillion, equivalent to more than 6 per cent of global GDP.

Nor is air pollution the only man-made phenomenon damaging our environment and the economy. Ocean acidification, water scarcity, and soil contamination also threaten our way of life.

Reversing these trends will take a monumental effort. Consumers will have to change their habits and governments their priorities. But it is investors who could perhaps have the most important role to play.

But their commitment is far from enough. The International Energy Agency estimates that for every USD1 spent to support renewable energy, another USD6 are spent on fossil fuel subsidy. Reallocating just 10 per cent of this spending to renewable projects, according to another study, would help pay for a transition to clean energy.[1]

As stewards of global capital, investors matter. And in two ways. On one hand, they can provide vital funding to the companies developing products and services that can reverse ecological damage. On the other, they alone have the power to withhold or withdraw capital from businesses that fail to take their environmental responsibilities seriously.

Requiring every listed company to account for its ecological footprint in the same way that it calculates, say, its revenues and profits, would be one way to deploy such leverage.

The problem, though, is the lack of meaningful data. Most of the environmental financial reporting available to investors is too narrow or too subjective. For instance, the standard corporate environmental analysis tends to focus exclusively on manufacturing process; they fail to take into account the wider ecological impact of, say, suppliers, or of the products and services over their entire lifespans.

Take car industry as an example. A car’s lifetime emissions are four to five times higher than those stemming from its manufacture alone. Just measuring the level of emissions during the car production process does not give a true assessment of automakers’ overall ecological footprint.

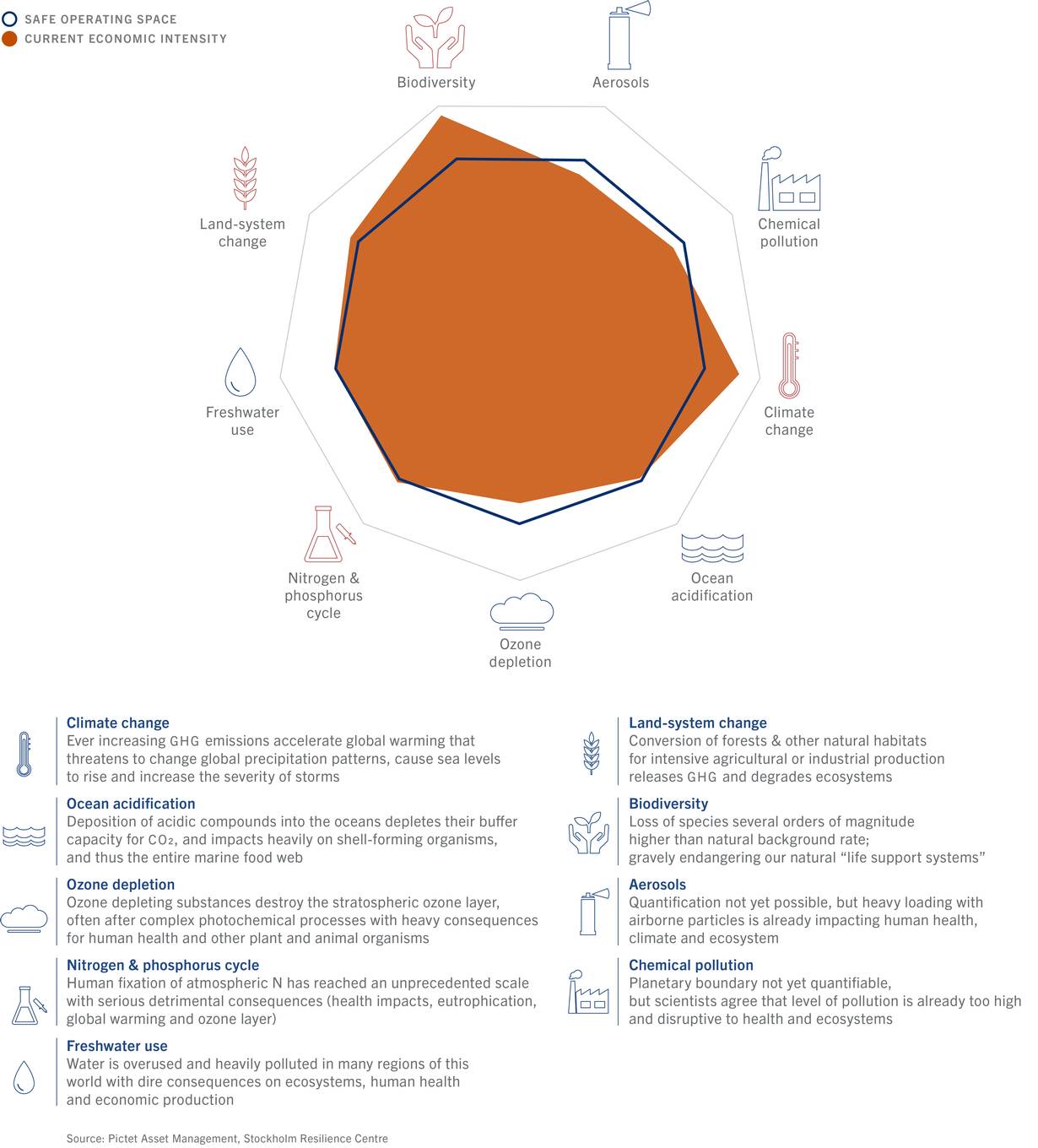

Similarly, today’s environmental debate tends to focus solely on climate change. But corporations -- and their investors – need to pay as much attention to their impact on biodiversity or water use as they do to their carbon footprint.

Investors should, then, broaden the scope of their corporate environmental auditing. One way to achieve this is to take a more scientific approach by using models such as the Planetary Boundaries. Developed by researchers at the Stockholm Resilience Centre, the Planetary Boundaries framework assesses the state of the ecosystem along nine environmental dimensions.[2] Encouragingly, this approach is beginning to get attention of big companies – with L’Oreal and Kering among the early adopters.

When scrutinising the environmental footprint of companies, investors should do so across their entire value chain: from the extraction of raw materials to manufacturing processes, distribution and transport, product use and disposable and recycling.

Many investors have long appreciated the need to protect the planet. They are uniquely placed to change the world for the better – if they use the right tools.

[1] International Institute for Sustainable Development

[2] The Planetary Boundaries (PB) identifies the ecological safe operating space that is essential to maintain a stable biosphere required for human development and prosperity along nine dimensions of climate change, ocean acidification, ozone depletion, nitrogen & phosphorus cycle, freshwater use, land-system change, biodiversity, aerosols and chemical pollution. Source: Steffen et all, Stockholm Resilience Centre