Forced from their homes by conflict over land and power, indigenous communities say they get no psychological support

By Oscar Lopez

SAN CRISTOBAL DE LAS CASAS, Mexico, April 15 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - Recalling the day she was forced off her land in southern Mexico by men shooting guns in the air and setting fire to her fields, Luz Magdalena de la Torre Vazquez is filled with despair.

The 45-year-old indigenous Tzotzil woman has since found refuge with family in the town of San Juan Chamula in Chiapas state, but the experience nearly two years ago has taken a heavy emotional toll.

"You can't even find the words to say what you're feeling," Vazquez said, wiping away tears. "There are times when it feels like there's no way out."

Indigenous victims of forced displacement like Vazquez face a range of challenges, from homelessness to disease and poverty, but researchers and activists say one of the most poorly understood issues is the psychological impact of their experience.

"They don't just lose their jobs: they lose their homes, they lose part of their family, and they also lose a whole series of cultural references," said Guillermo Castillo Ramirez, an anthropologist at Mexico's National Autonomous University.

"This can create a process of post-traumatic stress ... both because of the imminent violence and the uncertainty of what's going to happen," he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

In Mexico, a country wracked by violence - with a record 34,582 people killed last year alone - forced displacement has become increasingly commonplace.

The country's indigenous residents, who make up nearly one-quarter of the population of 120 million, are among the most vulnerable.

According to the Mexican Commission for the Defense and Promotion of Human Rights, out of the nearly 11,500 people forced off their land due to conflict across Mexico in 2018, almost half were indigenous.

Rural Chiapas is one of the country's worst affected: nearly all of the indigenous people displaced in 2018 in Mexico were Tzotzil residents of the southern state.

"In the history of Chiapas, there's been displacement for as long as I can remember," said Diego Cardenas Gordillo, a local indigenous rights activist.

The causes of forced displacement in Chiapas range from religious disputes to fights over farmland and political power struggles, most notably during the anti-globalization Zapatista uprising in 1994.

More recently, human rights advocates say, clashes between rival indigenous communities fighting over territory have forced many to flee their homes, with aggressors sometimes backed by armed militias funded by powerful political parties.

After decades of violent struggle, the psychological cost is starting to mount, said Pedro Faro Navarro, director of the Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Human Rights Center in San Cristobal.

According to Navarro, two indigenous youths have killed themselves in nearby towns over the last two years because of the seemingly unending conflict.

"There are people having panic attacks, people living with a great deal of fear and terror," he said.

A 2016 study published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research found that indigenous people were at greater risk of post-traumatic stress disorder than non-indigenous groups in the Americas.

But the study also noted that the lack of culturally-specific assessment tools made it difficult to accurately measure the extent of the issue.

'WE ARE THE EARTH'

For many indigenous people, who continue to depend on farming and livestock, being forced off their land means having their livelihoods ripped away.

Vazquez and her family used to grow corn and beans on their farmland in rural Chiapas, but now they are forced to go out onto the street, selling sweets or polishing shoes to eke out a basic living.

"I have nowhere to work," said Vazquez. "Before, I knew I had my crops, and I had to struggle for a certain amount of time, but it's not the suffering that we're living now."

"Sometimes there's no food," she said, adding that she often frets about feeding her four children.

Such worries can weigh heavily on displaced families, but beyond the economic stress, experts say forced displacement can have an even more profound impact due to the spiritual connection many indigenous people have with their territory.

"You have groups where their identity is strongly anchored to the land," said Ramirez, the anthropologist. "When you have a process of forced internal displacement ... for indigenous people, it's much more severe."

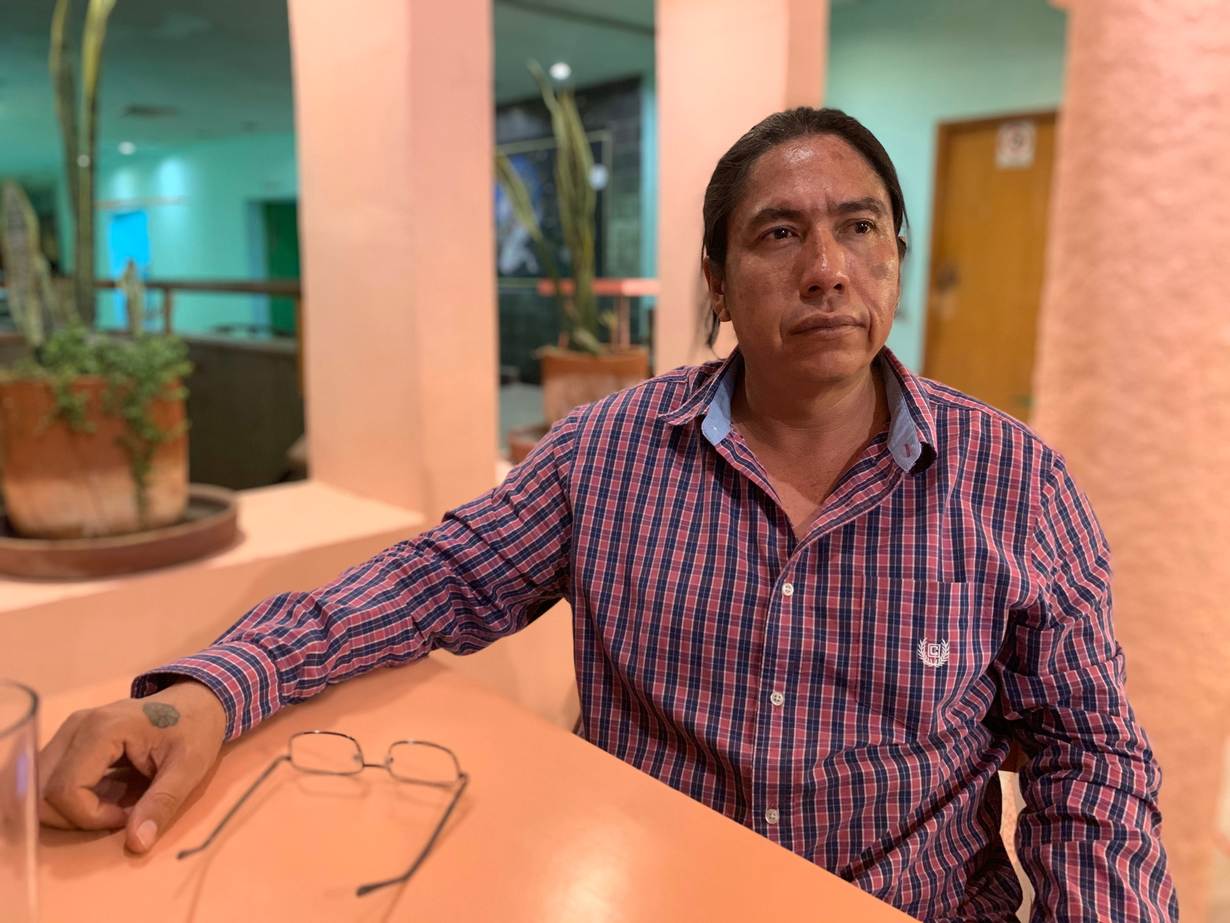

Rodrigo Santiz is the son of a community leader for Aldama, a village in the mountains of Chiapas where dozens of families have been forced to flee because of bullets raining down on them from an armed militia in a neighboring community, in a bitter fight over land.

"Religiosity is linked to cultural traditions, to prayer for the land, the hills, the fertilization of corn, coffee," said Santiz.

Without their land, Santiz said, the people of Aldama "are missing something. Because it is part of them. They are the earth. We are the earth."

WESTERN THERAPY

Making matters worse is a meager government response which offers little in the way of assistance, say indigenous advocates and displacement victims.

"(Government) actions have been ineffective and inefficient," said Navarro, from the Fray Bartolome human rights center. "They are not addressing the root of the conflict."

A spokesman for the Chiapas interior ministry did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Miguel Angel Aguilar Dorado, adjunct director general for the Mexican interior ministry's Center for Migration Studies, said the government's response so far to tackle forced displacement has been "very inefficient".

But he hopes a bill that would legally recognize forced displacement at the federal level will be approved in Congress by the end of the year.

For now, the government is providing short-term humanitarian assistance to some displaced groups, including medical and psychological support, he added.

"Forced internal displacement is always or almost always preceded by trauma," he said in a phone interview.

But campaigners said that local governments have contributed to this trauma by criminalizing activists.

Santiz's father, Cristobal Santiz Jimenez, was arrested in March on murder charges and taken to jail - Santiz said his father had never even met the woman he is accused of killing. The case is ongoing.

"It broke my soul," Santiz said, recalling the day his father was arrested and nobody knew where he was. "I couldn't believe it - I was in shock more than anything."

The lack of psychological help from the government is compounded by the fact that modern forms of therapy are ill-suited to indigenous ways of thinking, rights advocates say.

"It's a profound challenge because there's no mold for psycho-social attention in these communities," said Navarro. "The more Western model doesn't fit."

But cultural barriers aside, indigenous people say any kind of psychological support could make a big difference.

"It would be a great help," said Santiz. "To have ... a psychologist who could support us to find emotional stability in this situation we're living through."

Such assistance is tough to find: according to the Mexican government, there are only three psychiatrists and 18 psychologists in the whole country who work in indigenous-majority communities.

Without an outlet for their worries, indigenous victims say their negative emotions are left to fester inside.

"Each one of us needs to express and vent the feelings we're carrying," said Vazquez.

"More than anything it's rage, holding a grudge, hatred towards other people ... You keep that in, you think about it, you hold onto it. (But) we don't talk about it."

Related stories:

Language barriers, social distancing: Mexico's indigenous face coronavirus

A town torn apart: Mexico's indigenous communities fight for autonomy

FEATURE-'No to the mine' - Mexico's Indians fight to stop mining on ancestral land

(Reporting by Oscar Lopez @oscarlopezgib; editing by Jumana Farouky and Zoe Tabary. Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers the lives of people around the world who struggle to live freely or fairly. Visit http://news.trust.org)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.