A new benchmark shows big firms have poor policies on respecting land rights and supporting displaced communities

By Megan Rowling

BARCELONA, July 1 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - Companies that produce clean energy are crucial for curbing climate change - but they're not always the "good guys", according to a report that tracks their human rights record for the first time.

The Business & Human Rights Resource Centre (BHRRC) says 16 of the world's largest publicly-traded wind and solar producers are not doing enough to protect their workers and the local communities affected by their operations.

Here are the key takeaways:

What's the bigger picture?

A push to use less fossil fuel and curb climate change has seen nearly $2.7 trillion invested in renewables - mainly in solar and wind power - in the past decade, and the sector employed 11 million people in 2018.

Many of the companies are seen as saviours when it comes to tackling global warming - but the same can't be said of how they treat human rights, according to Phil Bloomer, BHRRC executive director

That is a particular concern for indigenous people whose land has in some cases been used for clean energy projects without their agreement or fair compensation.

Which companies have been assessed and what are the key results?

Spanish energy corporations Iberdrola and Acciona, followed by Denmark's Orsted and Italy's Enel, had the best human rights record overall, with French and German firms dominating the middle tier - but no company scores above 53% on the benchmark.

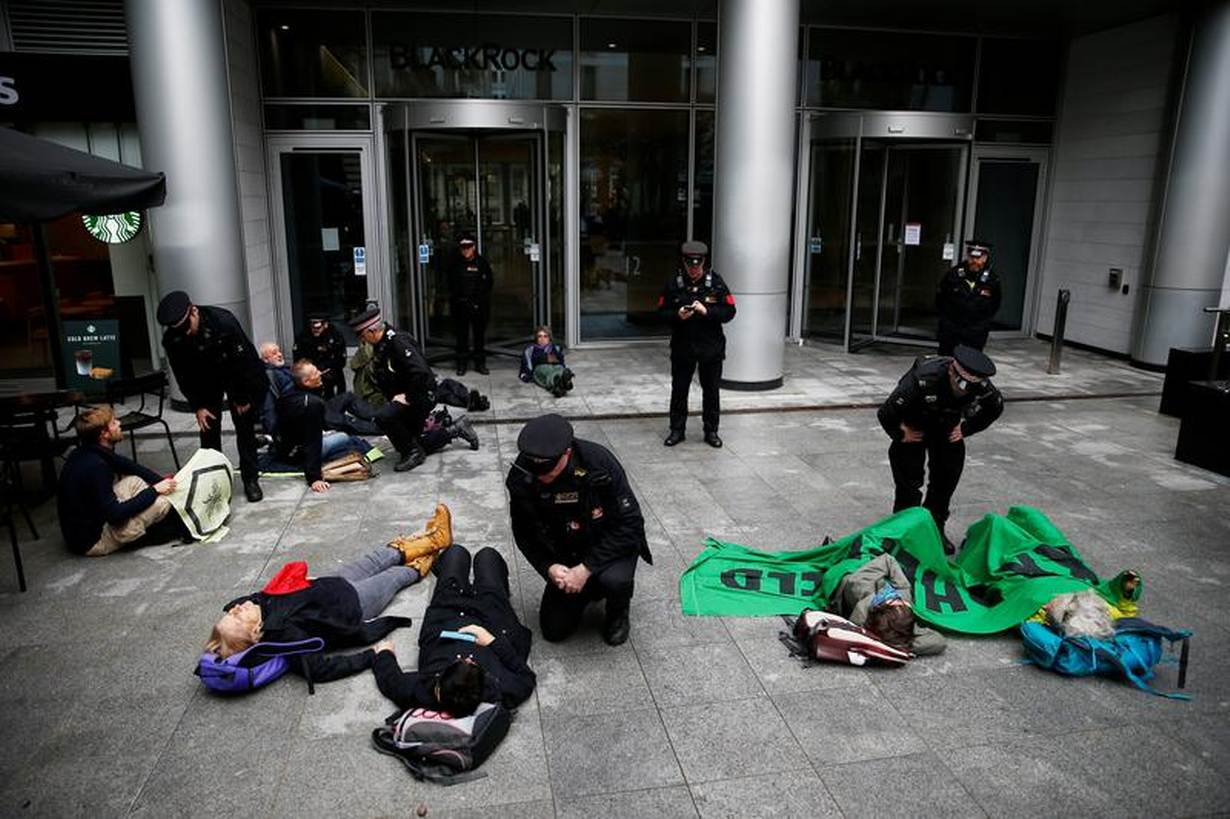

The worst performers are Chinese and North American companies, as well investors Brookfield and BlackRock, the world's largest asset manager, which own many renewable projects.

Companies, on average, scored better on indicators covering the basic human rights responsibilities, including having policies and grievance mechanisms in place, similar to other high-risk industries like apparel, agricultural products and tech manufacturing.

But they scored zero across the board when it came to commitments such as respecting local land rights and relocating or compensating communities affected by renewables projects.

The companies scored well in some areas, including anti-corruption due diligence and health and safety disclosures.

So big renewable energy firms are doing the right thing for the planet but the wrong thing for people?

The centre has tracked allegations of abuse against renewables companies over the past decade, and says complaints increased 10 times between 2010 and 2018.

Since 2010, the centre has identified 197 allegations of human rights abuses related to renewable energy projects, and asked 127 companies to respond to those allegations.

They include: killings, threats, and intimidation; land grabs; dangerous working conditions and poverty wages; and harm to indigenous peoples' lives and livelihoods.

Allegations have been made in every region and across the wind, solar, bioenergy, geothermal and hydropower sectors, with the highest number in Latin America.

Why is this happening?

Some of the biggest renewable energy players have evolved from companies whose main business was previously fossil fuels, and they were used to being able to act with impunity on the environment and human rights, said Bloomer.

But that is changing. There are a small number of leaders who are setting new, higher standards, and that will pressure others to catch up. If they don't, their reputations and ultimately their share prices will likely suffer, Bloomer added.

The goal of the new benchmark is to shine a light on problems and encourage transparency so that companies and investors will better understand the impacts on local communities, particularly in developing countries.

Are there examples of how renewable energy companies can be more responsible?

Firstly, there are cases in which indigenous groups have pushed back. They include a wind farm in Norway challenged by reindeer herders over loss of land and a wind farm in Kenya cancelled after lawsuits by farmers and local landowners.

And in some places, companies have gone into joint ventures with local communities, including in Mexico.

Bloomer cited Canada, where indigenous land rights are listed in the constitution, providing strong protection that has led to about half of wind and solar projects being co-owned by communities, a model that averts tensions and keeps assets safe.

What happens next?

Bloomer said some of the companies had helped develop the benchmark's methodology, and about 40% had participated in the wider process of drafting the report, including Iberdrola. Some have already made positive changes, he added.

BlackRock hit back at the report, saying it "fails to acknowledge BlackRock's many public commitments to upholding human rights standards across its business and investments".

It said it had not been consulted on the benchmark, although BHRRC said it contacted BlackRock and received no response.

In a report foreword, former President of Ireland Mary Robinson said a narrow focus on short-term returns regardless of the harm to people and the environment had led fossil fuel companies "to lose legitimacy and social licence to operate".

"If the same happens to renewable energy companies, it will only slow our expansion to a net-zero carbon future. That’s why we need clean energy that respects human rights," she said, calling for a green transition "that is fast, but also fair."

Related stories:

OPINION: Stopping land and policy grabs in the shadow of COVID-19

Peru indigenous leaders push quick Amazon protection vote, defying oil industry

As land conflicts rise, clean energy investors face financial risks

Africa's largest wind power project opens in northern Kenya

(Reporting by Megan Rowling @meganrowling; editing by Tom Finn. Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers the lives of people around the world who struggle to live freely or fairly. Visit http://news.trust.org/climate)