Poorer city residents - most of whom are Black - live in areas with fewer parks or green spaces, a new study has found

Coronavirus is changing the world in unprecedented ways. Subscribe here for a briefing twice a week on how this global crisis is affecting cities, technology, approaches to climate change, and the lives of vulnerable people.

By Kim Harrisberg

JOHANNESBURG, Aug 7 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - It took the new coronavirus to reveal a green apartheid lurking in South Africa's cities as parks shut, lockdown kept millions home and only the lucky few had a garden for sanctuary.

Satellite imagery shows this inequality blighted almost every South African city, with poorer, mainly Black residents living with less greenery and left with fewer options to stay safe from the deadly virus through social distancing.

"Every human should have a right to green space," said Zander Venter, a spatial ecologist at the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research and lead author of the Green Apartheid study published in the journal Landscape and Urban planning in July.

"Not having this is a violation of human rights that started with colonialism and apartheid, and the government today has failed to redress this spatial inequality," Venter told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in a phone interview.

Green spaces help cool down cities, clean the air, filter water and generally promote better emotional and psychological wellbeing for city dwellers, said Venter.

People in leafy neighbourhoods also tend to live longer, according to the Barcelona Institute for Global Health.

Using satellite imagery and census data, Venter was able to back up a hypothesis he had cooked while growing up in South Africa: that inequality existed in access to nature, too.

The study found that "white" neighbourhoods are 700 m closer to public parks, have nearly 12% more tree cover and 9% more vegetation than areas with predominantly Black residents.

South Africa's largest city, Johannesburg, calls itself one of the world's biggest man-made forests, with jacaranda-lined streets, lush dog parks and big gardens - in wealthier suburbs.

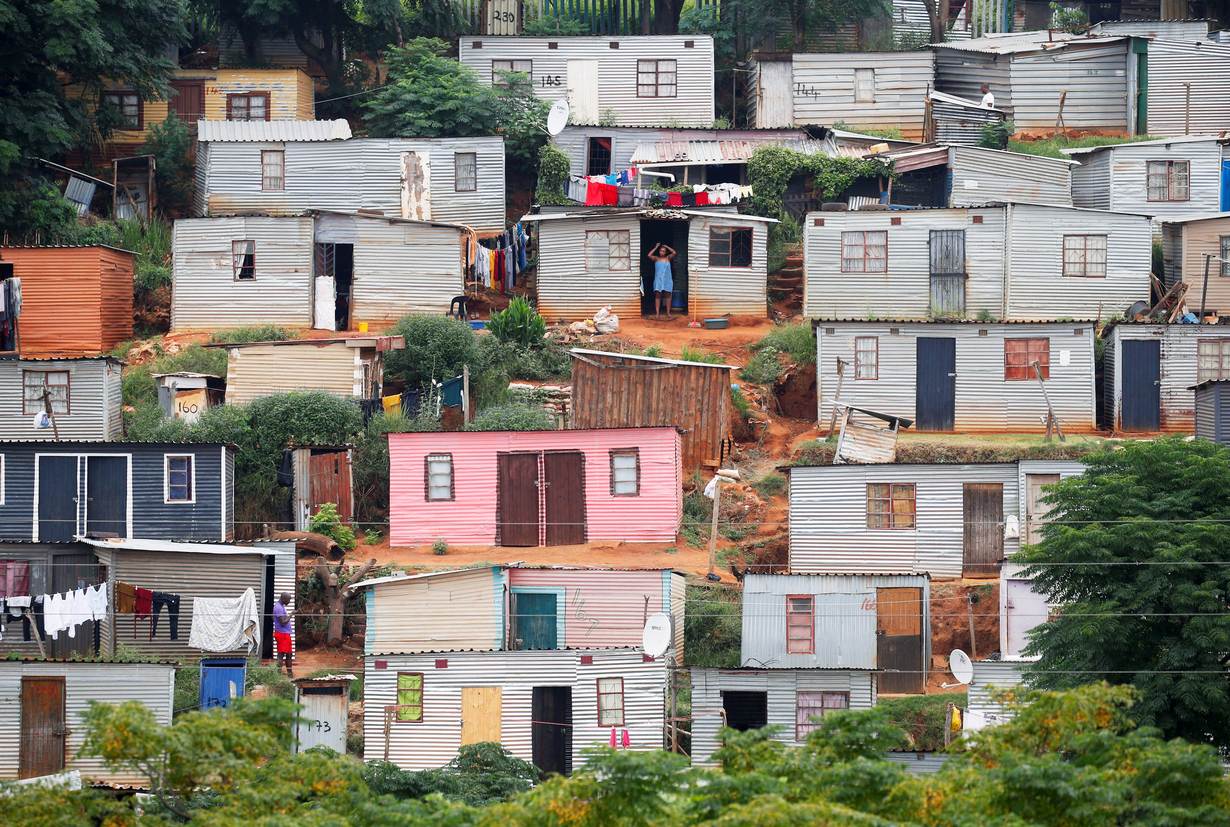

Compare this with mainly Black townships and informal settlements, where trees are scarce and roads dusty.

In the tourist hub of Cape Town, crowded informal settlements sit on the city's periphery, far from the verdant mountain trails and lush promenade that snakes along the Atlantic Ocean.

City official Ayanda Roji, head researcher at Johannesburg's parks, said greening projects were underway, but "three and a half centuries of colonialism/apartheid" took time to address.

URBAN UPGRADING

Apartheid planners used green spaces, highways and tracks to segregate racial groups, and the legacy is evident today, said Robyn Park-Ross of housing rights group Ndifuna Ukwazi.

"This means that our parks and open green space are not neutral spaces, they were designed as part of a system to keep people apart," Park-Ross said in emailed comments.

Depending on location, parks can also be crime hotspots and pose a risk to women crossing them, Park-Ross said.

Even in cemeteries, police have logged reports of rapes and muggings when mourners visit the graves of loved ones.

Fewer than three in 10 South African women feel safe walking at night, according to the 2017 Women, Peace and Security Index that measures safety in 153 countries.

"This means that not only the distance required to travel to access a park is defined by race and class, but also that your experience and ability to enjoy that space is too," said Park-Ross.

Some successes have been notched up to make treasured green spaces safer. Park-Ross cites Violence Prevention through Urban Upgrading - an organisation that fights crime by building community gardens, neighbourhood watch groups and more.

"Design was used as a tool to segregate our cities and now, alongside addressing the systemic inequalities that result in these spaces being unsafe, design must be put to work," she said.

RESILIENCE

Across the continent, green infrastructure is seen as an afterthought in countries where budgets are stretched thin to cover basics such as housing, sanitation and electricity, said Roji, from Johannesburg City Parks.

"This is why we are entering into partnerships," said Roji, citing women-led park rehabilitation and plans for outdoor gyms and food gardens.

The calibre of 'greening' is essential to creating the best spaces for everyone, said Park-Ross.

"Defensive architecture" such as spiky cacti used to deter the homeless or resident-only parks are examples given by Park-Ross of greening gone wrong.

Inclusive projects, said Venter, could on the contrary strengthen resilience against a possible future virus outbreak.

"A network of green infrastructure will facilitate social distancing and help people to de-stress in a healthy, safe way," Venter said. "This could be a great advantage in future pandemic-like situations."

Related stories:

Public space a 'lifeline' for post-lockdown cities

Protests, pandemic pile pressure on U.S. public space

Maze parks to micromarkets: How coronavirus could bring cities closer to home

(Reporting by Kim Harrisberg @KimHarrisberg, Editing by Lyndsay Griffiths. Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers the lives of people around the world who struggle to live freely or fairly. Visit http://news.trust.org)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.