Communities are using open source tools to help contain the coronavirus by mapping handwashing stations and those at risk

Coronavirus is changing the world in unprecedented ways. Subscribe here for a briefing twice a week on how this global crisis is affecting cities, technology, approaches to climate change, and the lives of vulnerable people.

By Rina Chandran

BANGKOK, Sept 14 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - After the coronavirus outbreak hit Indonesia, charity worker Harry Machmud in May asked volunteers to map handwashing stations across the sprawling archipelago.

Hundreds of volunteers who otherwise mark roads and bridges on OpenStreetMap (OSM), a free and editable map of the world being built by communities using smartphones and drones, added more than 1,100 handwashing stations across the country.

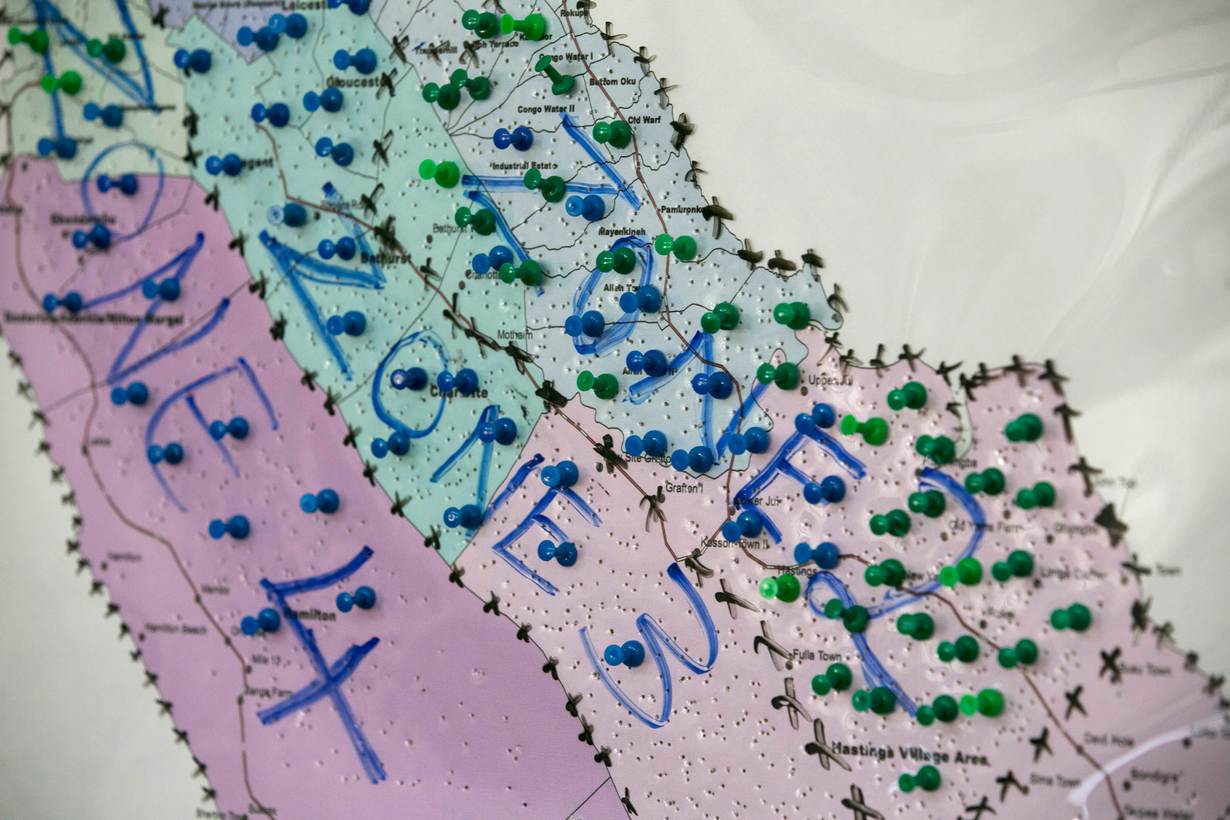

Worldwide, the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT), which uses mapping to support humanitarian action, has been getting updated OSM data to government agencies and healthcare personnel trying to reach vulnerable populations during COVID-19.

"Incomplete or inaccurate maps can cut off entire communities from essential services and government assistance," said Machmud, who heads (HOT) in Indonesia.

"OpenStreetMap lets the community update the map whenever they want to. It is based on their knowledge and their priorities, and they don't have to wait for government permission or for anyone else to do it," he said.

The coronavirus pandemic has highlighted many of the world's inequalities, from quarantine facilities to access to technology.

It has also underlined the importance of maps, that remain inaccurate and incomplete in many parts of the world, leaving more than one billion people "invisible", according to HOT, which aims to map these areas in 94 nations in five years' time.

Gaps in mapping data - from roads to buildings - in marginalised places impede response efforts of governments and aid agencies during disasters and emergencies, said Paul Georgie, founder of Scottish geospatial technology firm Geo.Geo.

Neighbourhood level mapping is particularly crucial in a pandemic, he said, pointing to the pioneering work of physician John Snow in mapping cholera clusters in London in 1854, which helped end the deadly outbreak.

"Citizen science data, whether through crowdsourcing or active participation, represents a valuable asset that has largely been ignored during this pandemic," Georgie told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

"The lack of accurate data directly hinders the ability to create accurate neighbourhood level maps of infections which help us understand the community-level vulnerabilities and impacts," he added.

PHONE CHARGING POINTS

The easy availability of open source technologies and access to satellite imagery and other modern tools means that mapping can be done by anyone from anywhere.

After Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico in 2017, HOT mobilised about 6,000 volunteers across the world who mapped every home and road on the island. Responders used those maps to assess the damage and give emergency cash, Wi-Fi and phone charging points.

Since 2010, about 250,000 HOT volunteers have mapped areas home to more than 150 million people globally.

These include people turning satellite images into maps by drawing buildings and roads on top of them, and local residents then identifying schools, hospitals and other markers on the maps using basic smartphones. The tool also works offline.

"You can map entire cities in just a couple of days," said Rebecca Firth, HOT's director of partnerships and community, adding that machine learning and artificial intelligence are helping mappers work more efficiently.

Such maps have been used in rescue efforts after the 2010 Haiti earthquake, to give polio vaccinations in rural Nigeria, and to plot the routes and camps of more than eight million refugees fleeing South Sudan, Syria and Venezuela, she said.

HOT is backing COVID-19 responses in 18 countries through mapping, including Peru where more than 10,000 volunteers have made nearly one million edits to the country's map, she said.

To reach its goal of one million volunteers, HOT is giving microgrants in countries including Liberia, Kenya and Mongolia, and engaging with university students and youth groups.

"Maps and geodata are most useful if they can be used before disaster strikes - when planning a response based on a hurricane forecast or in the early stages of an outbreak," she said.

"The data inequity is all the more stark when governments and NGOs respond to crises like the COVID-19 epidemic."

For LGBT+ rights campaigner Mikko Tamura, it was Typhoon Haiyan that struck the Philippines in 2013 that led him to become a volunteer mapper, when he realised the difficulty in getting relief to remote areas.

"Roads, schools, hospitals, water sources - when they are not on the map, communities suffer," he said.

"With a map, you are giving the community's knowledge back to them, so they can use it to better prepare for disasters. Maps show they exist, and allows them to plan for the future."

DIGITAL DIVIDE

The coronavirus pandemic is pushing even wealthy nations to address the digital divide, as more people are forced to work from home, and students have shifted their learning online.

Last year, some 87% of people in developed countries used the internet, compared with just a fifth in the least developed countries, according to the United Nations, which has said the digital divide is "a matter of life and death" in the pandemic.

It also poses a challenge to mapping, with wealthy nations building smart cities where "everything is located and recorded", while poorer nations struggle to afford technologies, said Alan Mills, a consultant with British charity MapAction.

MapAction has mapped clean water ATMs in Kenya and twinned that with data on local vendors selling soap products, to help reduce COVID-19 transmission.

It is also mapping possible threats and dangers to COVID-19 aid efforts from protests and strikes, Mills added.

With growing pressure on land from expanding populations and industry, and with easier access to technology, developing nations are increasingly using drones and satellite images to map rural and indigenous lands that were previously unmapped.

But while mapping is beneficial to communities, it can also lead to loss of community lands, and pose threats to women and indigenous people who have traditionally not had land rights, human rights experts say, as it makes it easier to identify and acquire lands without formal tenure.

This is why it is essential to train communities and involve them in mapping - not just in pandemics and disasters, but also for rural development, public health and natural resource management, said Georgie.

"Humans will always know and care most about the places closest to them. Local citizens will always be our best geographers."

Related stories:

No title, no problem: Land rights with digital maps, social media

With simple words, mapping apps help refugees, slum dwellers

An address unlocks new life for Indian slum dwellers

(Reporting by Rina Chandran @rinachandran; Editing by Zoe Tabary. Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers the lives of people around the world who struggle to live freely or fairly. Visit http://news.trust.org)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.