About 300 members of the Embera community are living outside a Bogota park, calling on the city to provide permanent housing

Coronavirus is changing the world in unprecedented ways. Subscribe here for a briefing twice a week on how this global crisis is affecting cities, technology, approaches to climate change, and the lives of vulnerable people.

By Anastasia Moloney

BOGOTA, Sept 17 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - For the past two months, Felicia Bitokayo from Colombia's indigenous Embera tribe has been sheltering from the rain and the cold Bogota nights with only plastic sheeting to protect her family.

She and about 300 other Emberas were forced to flee their rainforest reserves in Colombia's western Choco province at the beginning of the year to escape fighting by armed criminal groups.

The tribe traveled hundreds of miles to the capital, where some scrapped a living together selling handmade jewelry on the street, while others begged. Having already fled one crisis, they found themselves facing another: the coronavirus pandemic.

"We couldn't pay our rent. COVID stopped us from going out and selling our arts and crafts," said Bitokayo, crouched over a coal stove outside a park in downtown Bogota, where the Emberas have set up a makeshift camp.

Colombia's five-month lockdown, which began in March, meant they could no longer work as street vendors selling their handicrafts to earn what they needed to buy food and pay rent.

Eventually, many families were kicked out of their rented rooms, costing about $110 a month, and became homeless.

"It's hard when it rains. Water gets through under the sheeting," said Bitokayo, wearing traditional dress and a colorful beaded necklace.

Under cramped tents made from plastic sheeting held together with wooden sticks, the Emberas, including about 20 pregnant women and dozens of children, live in squalor. With no toilets, they are forced to defecate in the street.

Embera children run around barefoot, playing with rubbish and tattered kites next to a hand-painted sign reading: "Basic subsidies and decent housing for the Embera people."

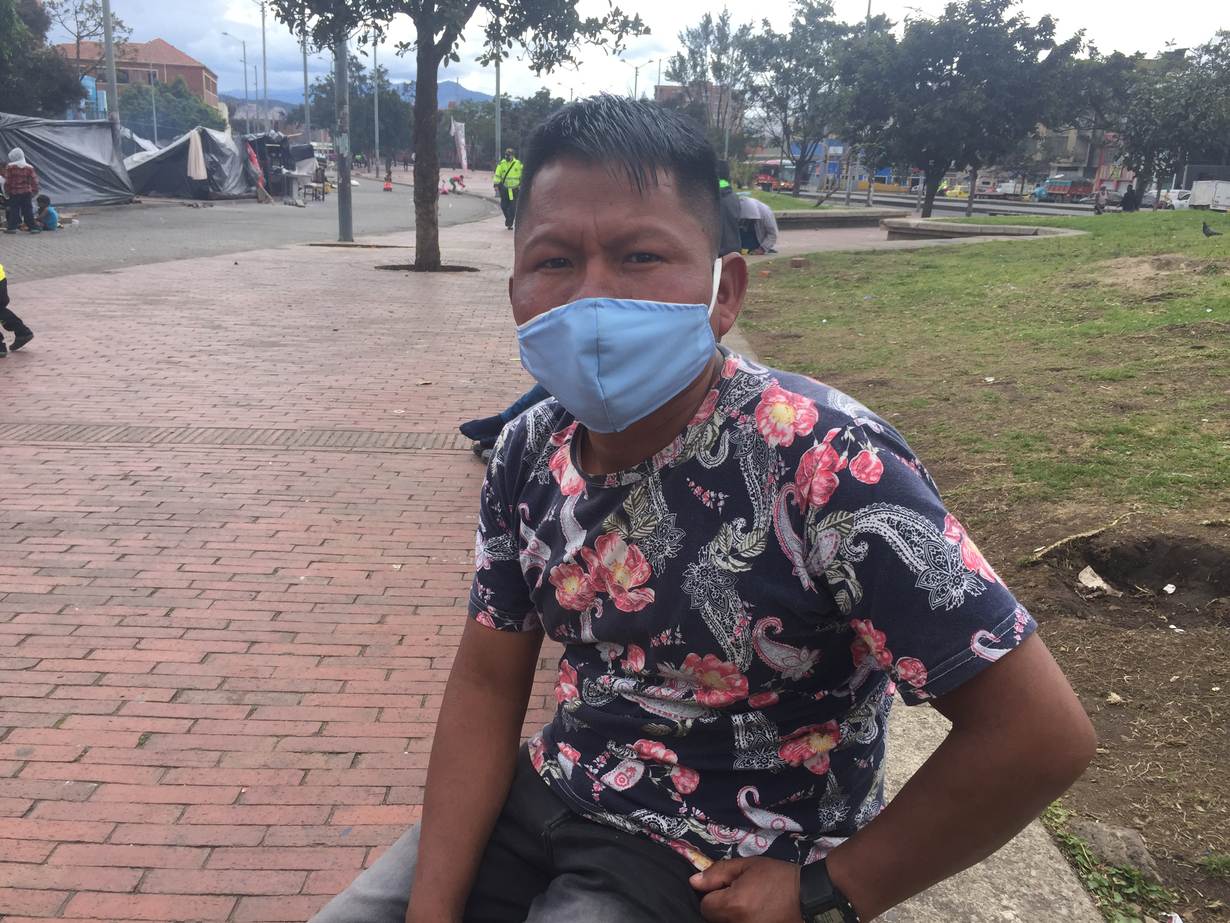

"We're here to demand our rights. We need housing," said Alfonso Manucama, a member of the Embera people, crouched inside his small, dingy tent.

RISING VIOLENCE

Despite a 2016 peace deal that ended a 52-year war between the government and the country's largest guerrilla group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), parts of rural Colombia have seen little peace.

Fighting over lucrative drug-trafficking routes and illegal mining has increased in rural parts of the country since the FARC rebels demobilized, leaving a power vacuum.

As armed criminal gangs battle each other, indigenous groups are often caught in the middle.

Tribes often live in remote jungle areas where the presence of the state military is weak, exposing them to attacks by armed groups who operate near or on their territory, researchers and activists say.

"The Embera flee heinous abuses in their territories in the western state of Choco," said Jose Miguel Vivanco, head of the Americas division for advocacy group Human Rights Watch.

"There, the ELN guerillas and the Gaitanist Self-Defense Forces of Colombia have for years engaged in brutal fighting while committing child recruitment, planting landmines and forcing thousands to displace," he said.

In recent weeks, the violence has intensified with a spate of mass killings that left at least 25 people dead, according to government figures.

In total, about 200 people have been killed in 55 separate incidents this year, including indigenous people and community leaders, according to Indepaz, a Bogota-based think tank.

The Embera people are a tribe of semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers with a population of about 30,000, according to the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia.

They live on ancestral lands in regions rich with gold deposits, which attract criminal groups looking to profit from illegal gold mining.

"Where there's mining, there's trouble," said Leonival Campo, an Embera indigenous leader at the camp.

"Peace didn't come to our lands. The armed groups are still there. They threatened us and told us to leave," he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

A 2011 law entitles victims of Colombia's conflict, which has killed more than 260,000 people and displaced eight million, to apply for financial compensation from the government.

Some of the Embera have applied collectively for compensation, Campo said.

"We want the state to recognize us as victims of the conflict and give us reparations," he added.

GOVERNMENT RESPONSE

The Bogota mayor's office has released several press statements saying it has provided aid to the homeless Emberas, with about 140 families receiving subsidies of up to $200 per family to help pay rent, as well as food and hygiene kits.

In recent weeks, several meetings between indigenous leaders and officials from the mayor's office to try to get the Emberas off the street and into housing have failed, according to Embera leaders.

The mayor's office has said it has offered to rehouse the Emberas in temporary shelters and at the city's main conference center. It did not respond to requests for comment.

But indigenous leaders say they need a permanent solution and reject the city's temporary housing offers.

"We're waiting so that we can resolve our situation. We need a roof over our heads, a private place of our own," said Campo.

Many of the Emberas say they would like to return to their lands, but fear they would soon be forced to flee their homes once again.

"It's not safe for us to go back right now," said Campo.

Related stories:

Colombia's displaced "highly vulnerable" to human trafficking - campaigners

Colombia was deadliest country for land rights activists in 2019

Coronavirus making it harder for Colombia's indigenous Wayuu to survive -HRW

(Reporting by Anastasia Moloney; Editing by Jumana Farouky and Zoe Tabary. Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers the lives of people around the world who struggle to live freely or fairly. Visit http://news.trust.org)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.