* Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Most garment manufacturers in Bangladesh willing to publish information on working and safety conditions

Naureen Chowdhury is a senior programme Manager at the Laudes Foundation, while Doug Cahn is head of The Cahn Group

Transparency has the power to transform the fashion industry - from the factory floor to the retail shop. While transparency is becoming a popular theme in industry discussions, there remains considerable apprehension around it. Demystify what transparency is – and what it is not – is key to understanding how it can bring systemic change to the Bangladesh ready-made garment (RMG) industry.

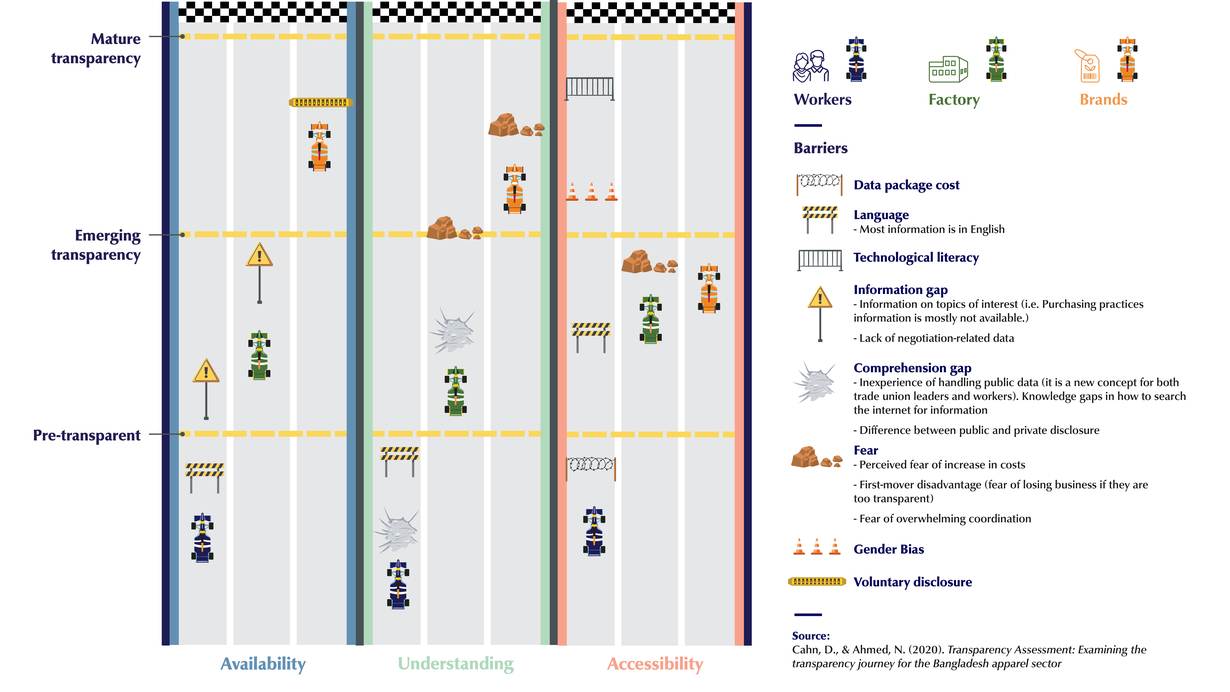

While there have been some improvements in the industry, there are significant barriers that still keep workers, manufacturers and brands from becoming more transparent – as can be seen in a visual framework mapped in our report: Transparency Assessment: Examining the transparency journey for the Bangladesh apparel sector. It shows where each key stakeholder of the fashion supply chain is on a continuum of transparency and indicates where interventions can be targeted for each group.

The 2013 collapse of Rana Plaza in Bangladesh is widely considered a turning point in global efforts to protect workers and ensure fair working conditions, using transparency as a way to improve accountability. Following this, Bangladesh has borne the brunt of the But despite this, the Bangladesh RMG industry (second largest in the world) has become a major participant in transparency initiatives. Public disclosure of inspections and corrective action plans have led to unprecedented transparency around fire, electrical and building safety conditions. This has, in turn, unlocked substantial improvements in safety and demonstrated that transparency can have real benefits for the sector.

The tide of transparency is growing, and more public disclosure seems inevitable. Acknowledging this, in 2017, C&A Foundation*, brought together 64 participants from the apparel supply chain in Chittagong to consider the benefits of transparency, to motivate greater action. It also stimulated partnerships that could establish Bangladesh as leader, change the country’s reputation in the apparel sector, and practically improve conditions for the workers whose labour powers the industry. The recently published report is an outcome of that meeting.

The report highlights the work of a number of initiatives like; Transparency Pledge, the Transparency Index, KnowTheChain, Open Apparel Registry (OAR) and Better Work. For example, Fair Wear Foundation (FWF) offers training and spreads awareness about labour standards. BRAC University’s Mapped in Bangladesh allows easy web-based access to basic factory information for all exporting clothing factories in the country.

A key finding of the report is that there is not a one-size-fits-all solution for workers, manufacturers and brands – each group is on a continuum with transparency meaning different things to each group. But rather than getting people to commit to full transparency – the continuum practically demonstrates how each group can progress to the next level of transparency along a spectrum that goes from pre-transparent, to emerging transparent, and finally mature transparency.

One of the most heartening discoveries is that manufacturers, including factory owners and managers, are willing to embrace transparency. A total of 61% said they believed greater transparency will improve Bangladesh’s reputation in the global apparel market, compared to competitors. And an overwhelming majority (87%) indicated they would disclose labour issues/working conditions and safety related compliance information publicly.

But the findings also reveal a distinction between a willingness to provide public access and versus limited access to records and information. Some manufacturers consider limited or private sharing of data as transparency. Due to the perception of inadequate social compliance performance, they fear that those who do make information public can open themselves up to criticism and a potential loss of business.

Transparency for workers can best be understood through the transparency performance of brands and factories. Worker transparency would be improved, for example, by better factory communication policies and procedures for workers in a language they can understand. One of the big catalysts to making transparency work, is for the publicly disclosed data to be used in ways that have an impact across stakeholders inside and outside the supply chain- in making better decisions -. For some user groups this will require building muscle to use data that has been previously unavailable. Transparency plays a critical role in democratising decision-making as all the main parties have access to the same information.

The outbreak of COVID-19 has affected the industry gravely and it is imperative to guard the progress that has been made around transparency to protect worker rights and ensure safe working conditions. We hope that the evidence on the transformative powers of transparency will establish it more firmly in the sector around the world.

While these goals may seem lofty, there is promising evidence that Bangladesh can play a leadership role if the various interest groups consolidate their efforts to maximise their impact and help create a culture of sharing and using publicly disclosed data. And from here, it is but a small step to think about reimagining the entire apparel industry globally – into a more just and equitable sector for all stakeholders.

*In January 2020, C&A Foundation became a part of Laudes Foundation