* Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Modern slavery is used by businesses to minimise costs, generate revenue and evade scrutiny of illegal practices

Genevieve LeBaron is a Professor of Politics at the University of Sheffield. Her co-authors - Andrew Crane, Kam Phung, Laya Behbahani & Jean Allain - are academics or doctoral students at various universities worldwide.

When business strategists and consulting firms talk about business model innovation, they emphasise game-changing advances that allows some firms to pull ahead of their rivals. Most of the time, such discussions revolve around positive capacities and win-wins for businesses and customers—like how fresh expertise and new technology can lead to better customer experiences, tailored products and lower prices while boosting company profits.

But business model innovation isn’t always this rosy. A dark side exists. Such wholesale changes in practices can also be profoundly negative for both workers and society. In our new article published in Journal of Management Inquiry, we uncover a dark form of business model innovation: how business models have evolved to keep profiting from slave-labour following slavery’s legal abolition during the nineteenth century.

Prior to abolition, many businesses were heavily reliant on enslaved labour. As slavery’s economic benefits became clear, businesses in the New World and far beyond reconfigured themselves to profit from forced labour. As the economic history of American plantations has demonstrated, using enslaved labour enabled plantation owners and managers to maximise revenue and minimise costs compared to waged labour, facilitating higher profit, though at the cost of dehumanisation and unfathomable suffering.

Fortunately, a world-wide abolitionist movement eventually succeeded in achieving regulatory reforms which ended slave-labour as a legal option for enhancing business profitability.

However, abolition itself did not mean the end of the use of enslaved labour by businesses as rather than letting go of their use of such labour, some businesses moved to further innovation, allowing for the retention of new forms of enslaved labour.

In spite of the fact that slavery is today illegal and carries with it a high risk of reputational damage, some businesses continue to use and profit from such exploitative labour. Unlike the business models from when slavery was legal, today business models configured around modern slavery tend to be more complex and take a variety of different forms, so as to both benefit from forced labour and to avoid detection of their illegal activity.

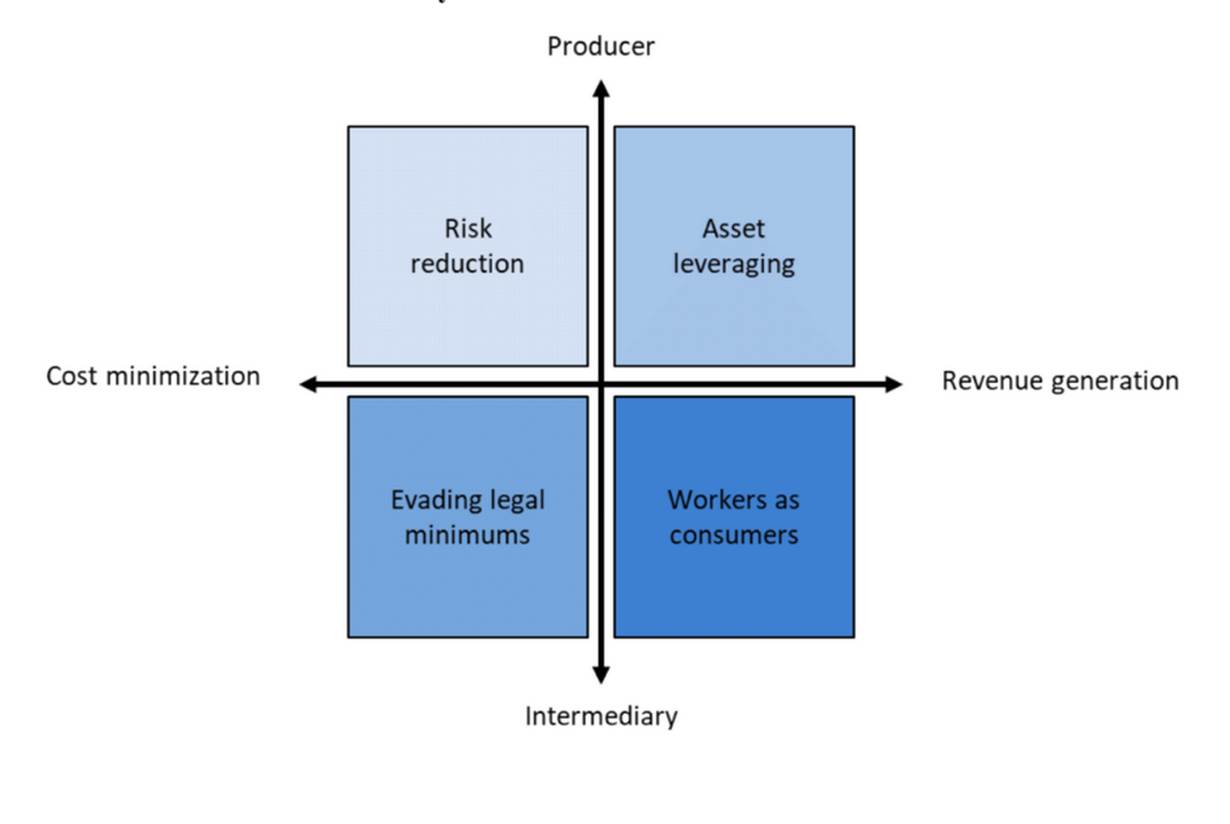

Drawing from our study of modern slavery in the UK’s agriculture, cannabis, and construction sectors, we demonstrate that the business models of modern slavery can be best captured by asking two key questions:

First, is the actor making money from modern slavery a producer (e.g. a farmer or garment manufacturer) or an intermediary (e.g. a labour provider or recruiter)? These groups of actors tend to introduce modern slavery into supply chains and capture value from it in different ways, so differentiating between them is key to mapping business models.

Second, how does that actor create or capture value through modern slavery? Is this by minimising costs, such as by not paying workers and then using coercion to stop them from seeking help? Or is value captured by revenue generation, such as when producers and intermediaries overcharge workers for services like transportation or housing?

The manner in which we identify and analyse business use of modern slavery is by turning to four models: risk reduction, asset leveraging, evading legal minimums, and workers as consumers (see Figure 1). These models tend to materialize in low-waged work, often where workers confront precarious, short-term, and informal conditions.

In a risk reduction model, producers seek to minimize costs as well as risks through illegal labour practices. For instance, an illegal producer such as a cannabis grower may seek to guard against the risk of being reported to the authorities through forced labour. Or a legal producer such as an agricultural or construction firm that is using illegal labour practices – such as paying below the minimum wage or requiring forced overtime – may use forced labour as a strategy to reduce the risk their illegal practices will be detected through social auditing or labour law enforcement.

With an asset leveraging model, producers use modern slavery to generate revenue. They do so by leveraging their assets (e.g. housing, transportation owned by the business) to charge workers for using them, often at usurious rates. Furthermore, businesses leverage workers’ assets, rights, and privileges, such as by enrolling victims of modern slavery in government benefits and then stealing these.

In a model configured to evade legal minimums, labour market intermediaries such as recruitment agents, labour providers, and gangmasters introduce forced labour to compress labour costs below legal minimums.

Regarding a worker as consumers model, the intermediary seeks to generate revenue not only from providing labour to clients at rates compressed below legal minimum wage, but also by charging workers for services such as accommodation and food.

Pinpointing modern slavery as a business model innovation enables scholars— as well civil society, industry, policymakers, and regulators— to understand where, when, and why modern slavery is used by businesses.

Seeing modern slavery as a component of a business model deployed by enterprises, instead of a practice that appears randomly and sporadically within the economy is key to focusing on those portions of supply chains where exploitative labour is most likely to take place, and which types of businesses are most likely benefiting from modern slavery.

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.