By Kim Harrisberg

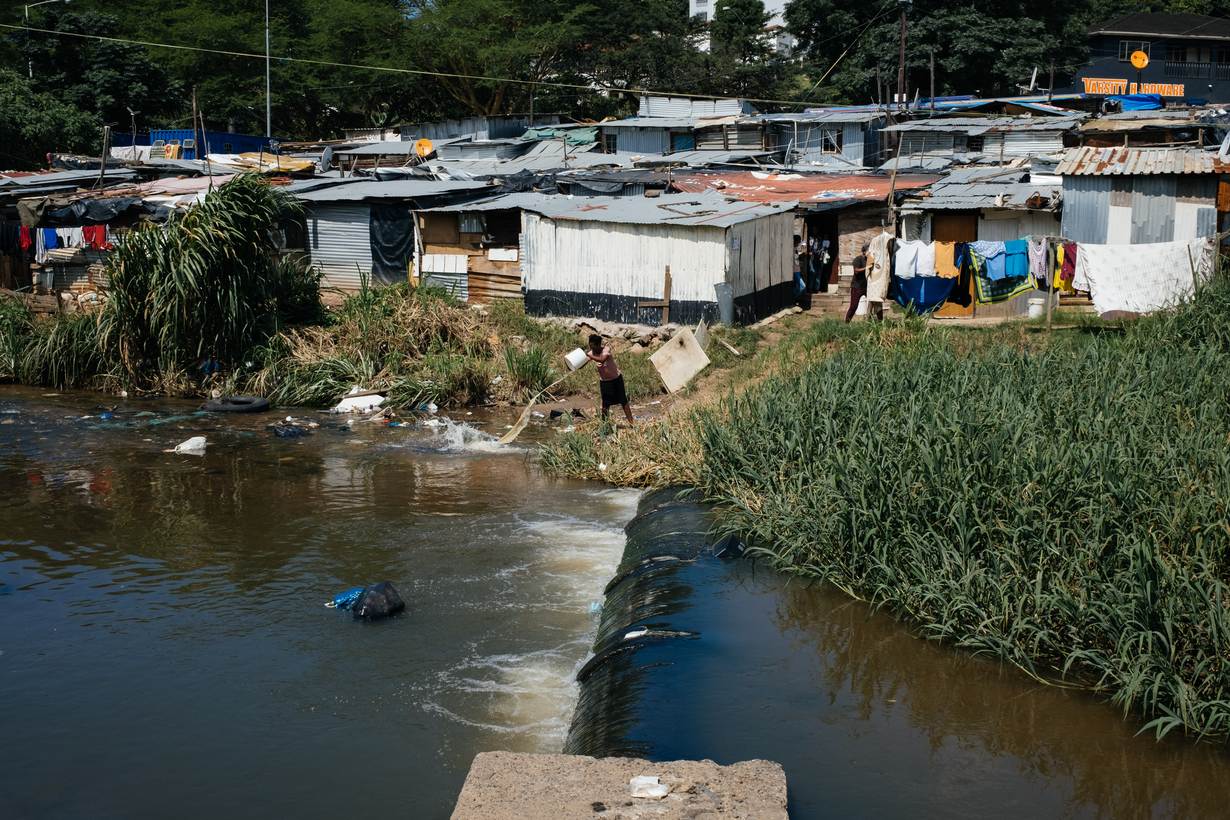

DURBAN, South Africa, May 18 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - A fter heavy rains swept away Nomandla Nqanula's tin shack two years ago, she would pray whenever she saw clouds gathering over the fast-growing Quarry Road informal settlement in Durban.

But these days, a WhatsApp group on her smartphone pings with flood warnings and another city-designed app reminds her and 14 other residents to monitor flooding risks and river pollution near her home.

"When I wake up, I feel I have lots of work to do, to protect the river and also protect the people who live here," said the 33-year-old mother, standing outside her shack.

Nqanula is an "Enviro-Champ", a resident selected by the city in 2019 to help tackle pollution and climate-related shocks, from illegal dumping to river erosion and floods.

Seaside Durban, South Africa's third-largest city with more than 3 million people, is part of the C40 Cities Network, a group of nearly 100 large cities around the world working to drive faster action on climate change.

The cities have each committed to delivering climate action plans designed to turn the 2015 Paris Agreement to tackle climate change into an on-the-ground reality and, more recently, spur a green recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Last September, Durban released its first Climate Action Plan, outlining strategies to green its energy, prevent flooding, improve waste management and conserve water, with a goal of becoming carbon-neutral by 2050.

Itumeleng Masenya, an emissions reduction specialist for eThekwini Municipality, which oversees the city of Durban, said prioritising vulnerable residents is a key focus, with more than a million estimated to be jobless and many at risk of growing climate threats, from floods to droughts.

"We are facing a balancing act. We need to reduce emissions but also create economic opportunities," Masenya said.

But slum residents say new green initiatives have been slow to come their way and when they do, they get little say.

High levels of inequality, recent court cases over municipal corruption involving the city's former mayor and gaps in communication have hampered progress, activists said.

They are demanding a stronger voice for local people - especially the most vulnerable - in plans to tackle climate change, environmental pollution and other problems.

"Climate change affects the poor," said Desmond D'Sa, co-founder of the South Durban Community Environmental Alliance (SDCEA), an environmental justice organisation.

"If the city wants solutions, they need to consult people affected by floods and pollution ... where they live," said D'Sa, a winner of the international Goldman Environmental Prize for grassroots eco-activists.

The city mayor's office did not grant repeated requests for an interview to explain its programmes and respond to residents' concerns.

DIRTY INDUSTRY

Durban's strategies to cut its emissions and lower climate risks for residents range from grassroots initiatives such as the Enviro-Champ push to rehabilitating coastal dunes as a buffer against encroaching seas and shoreline erosion.

The city is also trying to manage its waste better and reform laws so emissions from all new buildings reach net-zero by 2030, even as climate change brings hotter temperatures and more need for air conditioning including in its seaside hotels.

Durban is also an industrial hub, home to oil refineries, petrochemical companies, paper factories and a bustling port.

Durban's most recent greenhouse gas inventory shows industry is responsible for 32% of city emissions, with transport contributing 40%, homes 13% and the commercial sector 9%.

To lower industry emissions, Durban's climate strategy envisions a pivot towards renewable energy, including training programmes to boost its use and more industry energy audits.

But residents say that, over the years, the city's industries have caused an air pollution problem that can aggravate cases of COVID-19 during the current crisis.

Standing between the recently shuttered Engen oil refinery on one side and the crashing waves of the Indian Ocean to the other, SDCEA air quality officer Bongani Mthembu pointed to homes stacked alongside factories and fuel infrastructure.

Their location is a legacy of apartheid spatial planning that placed mostly Black communities in noxious industrial zones, environmental activists said.

"The air quality here is terrible. People that live here have cancer and asthma, but they can't relocate because it's expensive," Mthembu said.

Engen and major refinery SAPREF, which is also located in Durban, did not respond to emailed queries on pollution levels.

SDCEA uses a low-cost measuring system to capture and analyse air, which Mthembu said had detected "a whole cocktail of carcinogenic chemical emissions over the years." Siva Chetty, a chemical engineer with the city's air quality management team until 2011, said he was not aware of any data being published since he left.

To achieve its climate aims and clean up pollution, the city will need to tighten its regulations and enforce them with laws and fines, Chetty said.

'HELP OURSELVES'

In Durban's Kennedy Road informal settlement, which has grown up along a steep hill since the 1970s, shacks are crammed against each other, creating a collage of corrugated iron strung together with wires carrying illegal electricity supplies.

"People in informal settlements face shack fires, floods, overcrowding and poor sanitation," said Sibusiso Zikode, a founding member of Abahlali baseMjondolo, a national slum-dwellers movement.

Trucks roll in throughout the day, dumping an array of waste, including sand, cardboard boxes and old electrical appliances, at the adjacent Bisasar Road landfill, where locals work as wastepickers and recyclers.

A gas-to-electricity project was launched in Bisasar in 2007 to convert methane emissions from rotting rubbish into electricity. Local government reports say the landfill was set to stop receiving waste altogether in 2015.

But informal dumping continues, and smoke billows into the air as workers burn the plastic coverings off old wiring, to harvest the valuable copper inside for recycling.

The city's climate plan aims to halve the amount of waste put in landfill sites by 2023 and cut it 90% by 2050 through more recycling and reuse of waste, to reduce emissions.

The effort includes community awareness campaigns, more recycling containers in high-density housing areas, efforts to formalise waste-picking and plans to construct a new waste-to-energy trash incinerator.

In the north of Durban, Buffelsdraai, a newer methane-capturing landfill, could slash 10 million tonnes of climate-changing gases over its lifetime, according to the C40 website.

D'Sa said activists had not been allowed in to verify its processes, and city officials did not reply to requests for information about the project.

Besides managing waste better, Durban's climate plan aims to green slum neighbourhoods through tree-planting, as well as build climate-resilient homes and manage stormwater overflow.

But some residents, including Fiona Ndlovu, a 62-year-old former domestic worker who lost her job during the pandemic and had to turn to waste-picking, question the ambitious aims.

"We are poor, the government is poor, so we better just help ourselves instead of waiting for help," she said.

($1 = 14.3003 rand) (Reporting by Kim @KimHarrisberg. Editing by Laurie Goering and Megan Rowling. Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers the lives of people around the world who struggle to live freely or fairly. Visit http://news.trust.org)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.