With no one jailed over Lebanon's financial collapse and the probe into last year's Beirut port blast suspended, digital activists say naming and shaming politicians is more crucial than ever

* Lebanese angered by impunity for blast, financial meltdown

* 'Doxxers' post private information on politicians and bankers

* Activists say lack of official justice leaves no other choice

By Timour Azhari and Maya Gebeily

BEIRUT, Oct 5 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - Livestreams of politicians being harangued at restaurants and screenshots of bankers' addresses: frustrated by the lack of accountability for their country's collapse, Lebanon's digital activists are doling out their own form of virtual justice.

These activists are sharing the personal details and real-time locations of those they blame for Lebanon's financial tailspin, which has pushed more than three-quarters of the population into poverty, and for last year's Beirut port explosion, which left more than 200 dead.

The posts - a practice known as "doxxing" - often encourage anyone nearby to approach those pictured and berate them for playing a role in the country's meltdown.

The hope, they say, is that a public naming-and-shaming could provide relief for grieving families or serve as a temporary stand-in for justice through the courts.

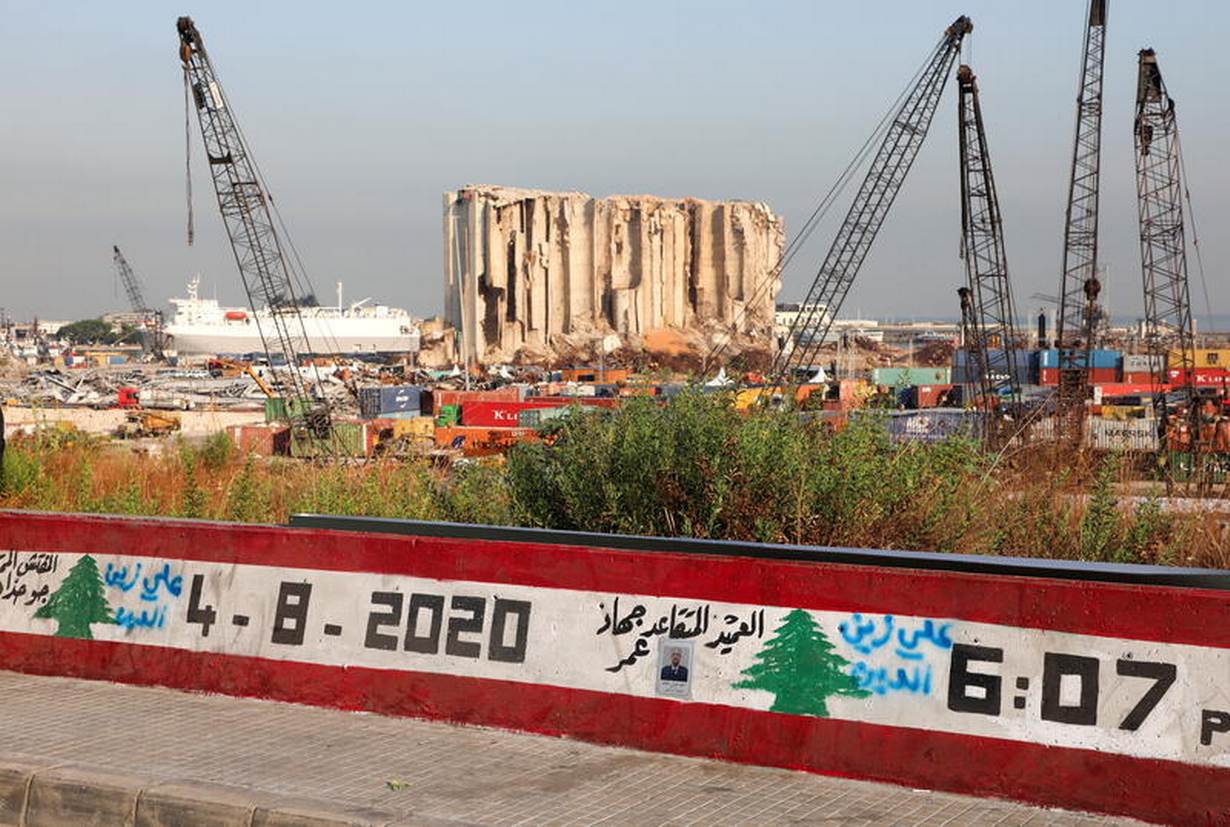

"When we see posts coming from these digital vigilante groups, we feel we're not alone," said Paul Naggear, an engineer whose 3-year-old daughter, Alexandra, was killed when a massive stockpile of combustible chemicals stored unsafely at Beirut's port exploded on Aug. 4, 2020.

He spoke to the Thomson Reuters Foundation just days after Lebanese authorities suspended an investigation meant to uncover who knew about the huge quantity of ammonium nitrate that had been stored at the port.

"In a country where justice is non-existent, I cannot think of another way (other than doxxing). It means the population takes justice – and the execution of justice – into their own hands," he said.

Lebanon's justice minister could not immediately be reached for comment.

Public interest in the private wealth of political figures has grown since Lebanon's deepening economic crisis.

A massive leak of financial documents was published by several major news organizations on Sunday that allegedly tie world leaders to secret stores of wealth, including Prime Minister Najib Mikati, ex-premier Hassan Diab, and central bank governor Riad Salemeh.

SPOTTED AND SPAT AT

The most prominent among the virtual vigilantes is ThawraMap, an Instagram page established in 2019 by anonymous activists who wanted to provide logistical support to anti-establishment protests in Lebanon.

"This evolved into helping spot politicians in public spaces and taking more responsibilities, such as showing their luxurious lifestyles and travels while (regular) people cannot access their own money," a page administrator said in written responses via Instagram.

The comments were referring to banking restrictions that have locked most Lebanese out of their savings over the last two years.

Using "live" reels, the platform crowdsources and publishes information on everything from a banker's lunch order and the names of Lebanese security guards seen beating up protesters to the company catering a politician's daughter's wedding.

Then it asks its more than 50,000 followers to shun the targets.

Lebanon's political elite are feeling the heat.

May Khreich, a senior official in the Free Patriotic Movement, Lebanon's biggest Christian political party, said she "goes out less" after having her whereabouts posted on line and being accosted three times in different parts of the country over the past 18 months.

"It's always tense – if I'm out somewhere and (anti-government Lebanese) are there, sometimes they come near me and other times they don't, they just stare at me," she said in a phone interview.

In July, Mikati said politicians were "ashamed to walk on the streets," and other officials have banned photos from events they are attending to avoid leaks.

That means the push for accountability is working, said Gino Raidy, a prominent blogger who earlier this year encouraged people to boycott a list of restaurants and venues whose owners he said were politically affiliated.

"These people are criminals, and they shouldn't be able to live their lives normally or go out as if they did nothing, when they are implicated in all the problems Lebanon is facing," he said.

ACCOUNTABILITY

These activists are treading a precarious legal line, said Linda Kassem, a policy advisor at the economy ministry who co-drafted Lebanon's 2018 digital privacy law.

Some posts sharing private information could be considered illegal, she explained.

"If they don't have the consent of the subject, this means that they are violating the law," Kassem said.

The 2018 privacy law slaps violators with up to three years in prison and a fine of between 1 million and 30 million Lebanese pounds, currently equivalent to a real market rate of roughly $70 to $2,000.

Posts deemed libellous could be further punished under the country's press law and penal code.

Raidy, the blogger, has been brought in for questioning several times in recent years over his activism, but most others, including ThawraMap, are anonymous - and prefer to stay that way to avoid legal trouble.

Like other virtual vigilante movements around the world, Lebanon's doxxing wave has sparked debates about accuracy - some individuals have been misidentified as being linked to politicians - and ethics, as shunning campaigns have begun to include the children of government officials.

Naggear acknowledged the tactics are unorthodox, but said they are necessary as long as formal accountability remains out of reach.

"There are a lot of people who are not comfortable with it, and you see a lot of reactions like, 'What do their children have to do with it?' It is controversial, but in the end, what other methods do you have to apply pressure?" he said.

"We don't have another choice."

($1 = 1,505.5000 Lebanese pounds)

RELATED STORIES

Meet the virtual vigilantes who bust human traffickers from their laptops

Young Lebanese driving crypto 'revolution' after banks go bust

As Lebanon's economy unravels, dollar bills and connections pay off

(Reporting by Timour Azhari (@timourazhari) and Maya Gebeily (@gebeilym). Editing by Jumana Farouky and Zoe Tabary. Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers the lives of people around the world who struggle to live freely or fairly. Visit http://news.trust.org)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.