As they face rising risks on the road, food delivery drivers around the world are pushing gig platforms for better working conditions

By Kim Harrisberg

Nov 22 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - From leg amputations in Thailand to hijackings in Nigeria, millions of food delivery drivers around the world find themselves torn between the desperation to make a living and the fear that each ride may be their last.

The gig economy has surged during the COVID-19 pandemic and brought with it a wave of concerns from drivers and researchers who say that dangerous roads and inadequate safety equipment and training are putting lives on the line daily.

By 2020 there were at least 777 digital labour platforms - from food delivery to web design - around the world, up from about 140 a decade earlier, according to the International Labour Organization (ILO).

In the United States alone, the revenue of the country's top four food-delivery apps more than doubled over a five-month period in 2020 - at the height of COVID lockdowns - to about $5.5 billion, according to financial analysis site MarketWatch.

Couriers from South Africa to Mexico say they increasingly have to compete for trips to make up for lost income, with the influx of exhausted drivers and what they warn is a lack of training and safety equipment leading to more accidents.

MULTIMEDIA: Day in the life of a food delivery driver around the world

While researchers and activists say insurance coverage by gig platforms is becoming more common, many drivers report receiving insufficient payouts - or none at all - leaving them to sink into debt to pay off medical bills, bike repairs and loans.

"These platforms operate in a legal grey area that allows them to evade regulation and labour protection," said Kelle Howson, a researcher at Fairwork, a research project on the global gig economy at Britain's Oxford Internet Institute.

By classifying workers as "partners", said Howson, platforms are able to bypass many social security measures like health insurance or sick leave that are outlined as a universal right by the ILO. "The entire onus of everything to do with our lives, ourselves, our bikes, the fuel is on us ... it's completely unfair," said Rahul Singh, a 42-year-old former food courier in Mumbai who asked to use a pseudonym.

Singh quit his job after he was hit by a drunk driver in June, leaving him with an injured ankle and a limp. His motorcycle was badly damaged and he received no insurance payout from his employer despite claiming for one, he added.

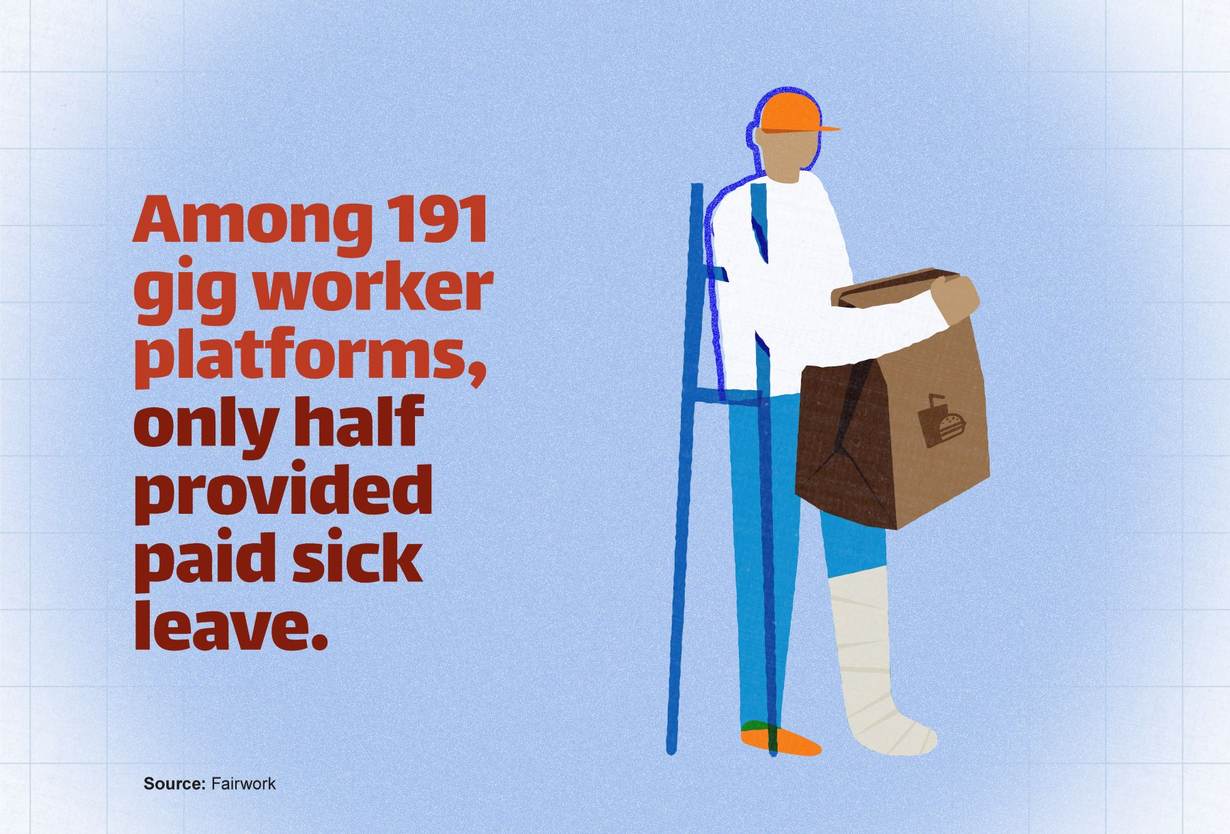

Fairwork researched gig work conditions in 43 countries globally and found that about half of 191 platforms report providing some paid sick leave, which workers say is often hard to claim for.

Now workers are questioning these policies in court, on social media and in protests from Kenya to the United States - with some success.

In July, Uber South Africa changed its insurance policy following a Thomson Reuters Foundation expose about the mounting risks faced by drivers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Now, drivers qualify for a payout after 24 hours spent in hospital, down from 48.

In August major gig platforms in Australia like Deliveroo and Uber Eats jointly developed safety principles for food delivery drivers, including access to protective equipment and safety training.

And France now requires gig platforms to cover the accident-related insurance costs of self-employed workers, while since the COVID-19 pandemic Ireland provides sick leave to all platform workers.

RISING THREATS

In India, where gig work researchers estimate there are half a million food couriers working mainly for Zomato and Swiggy, both orders and accidents spiked during the pandemic, as drivers increasingly took jobs and risks on the road to make ends meet.

Kaveri Medappa, a PhD resident at Britain's University of Sussex who works on India's food delivery drivers, said accidents involving couriers happen on a daily basis in her home country, with fatal accidents becoming more common.

Food couriers in other countries report similar challenges.

Mexican activist group Ni Un Repartidor Menos ("All Delivery Drivers Count") estimates there are about 3 million delivery drivers, most of whom have seen their pre-pandemic earnings drop from about 2,500-3,000 pesos ($124-$150) per week to 1,150-1,300 currently.

In Georgia, licences are not legally needed to drive a scooter - so gig platforms do not require them either.

But unions say road accidents involving food couriers are so common that parliament passed a law this month that will require moped drivers - who are almost exclusively food delivery drivers - to hold a driving licence and register the vehicle.

Road safety is not the only threat faced by drivers.

"We get several calls a week from drivers who have been assaulted, harassed, or battered," said Bryant Greenling, a lawyer and founder of LegalRideshare, a law firm based in Chicago.

"(Food couriers) are sitting ducks for criminals," he said.

LegalRideshare has represented more than 50 food couriers in U.S. lawsuits on issues ranging from accidents and assaults on the job, to driver account deactivations, Greenling added.

In Nigeria, Uber driver and union activist Ayoade Ibrahim estimates that there are some 20,000 food couriers and about 18 drivers lose their lives each month to accidents and hijackings.

"Another problem is dealers using drivers to transport drugs hidden inside food parcels, putting them at risk of arrest," said Ibrahim, who is also the vice president of the International Alliance of App-based Transport Workers (IAATW), a global gig worker association.

POLICIES AND CAVEATS

While gig platform researchers like Howson estimate that accident insurance exists in dozens of countries, they say health insurance is much rarer, and both types of policies often come with caveats.

"The devil is in the detail with these insurance policies," said Howson.

Thai drivers for local food delivery companies like Line Man say they have to hit 350 deliveries per month to qualify for a free month-long accident insurance cover, capped at 50,000 Thai baht ($1,480) in case of death.

A spokesperson for Line Man did not respond to several requests for comment.

In Nigeria, Estonia's Bolt, which launched in 2019, told drivers in an August email seen by the Thomson Reuters Foundation that the first 1,200 drivers to complete 200 trips in one month would receive a month of free healthcare.

Bolt did not respond to requests for comment.

"It feels like our lives are reduced to a promotional offer, a competition," said Ibrahim.

In India, a dozen food couriers said they received no safety equipment or training to do their jobs, with similar reports from drivers in Nigeria and Thailand.

"Platforms see it as crucial to their business model to insist that workers are independent," said Howson, and that by providing protective gear platforms would tacitly acknowledge responsibility, opening them up to legal challenges.

Even where insurance cover is available, drivers say that caveats such as time spent in hospital or capping payment to a number of days prevent them from fully benefiting from the policies.

In Georgia for example, Wolt's insurance covers damage to a third party's property but not that of the courier, leaving them to cover the costs to repair their vehicle.

Wolt said insurance covering couriers' personal property is not within the company's current scope "as such insurances would require employment status, which is something our partners do not wish."

Gig platforms Swiggy and Zomato in India said they offer a range of support for couriers including accident cover, medical insurance and a 24/7 helpline.

But a dozen drivers interviewed said that payouts can take so long to come, if ever, that they instead turn to family and friends to take out loans after an accident.

Pratap, a 26-year-old food courier in West Bengal who fractured his arm in a road accident last year on the job, turned to his network to help pay for hospital treatment.

"I needed the money fast ... I thought 'Should I wait for the endless back-and-forth, the paperwork or should I just ask the people who actually care for me for a loan?' – I went with the latter ... It just made more sense."

'CAN BE POSITIVE'

From anonymous Twitter accounts to WhatsApp and Facebook groups, food delivery drivers around the world are going online to share stories, support and fundraise for injured colleagues, often using these spaces to plan protests or strikes.

Between January 2017 and May 2020 there were at least 527 reports of global unrest from food delivery workers - such as protests, strikes and legal cases - according to German charity Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

Court cases challenging working conditions for drivers are mushrooming from South Africa to Britain, with Uber in February agreeing to offer work entitlements to its more than 70,000 UK drivers.

In some countries, entrepreneurs and couriers are trying to reshape the gig sector's social security system themselves.

South African social enterprise MotionAds sells branded advertising space on delivery bikes, with drivers getting a cut of the campaign spend plus benefits like roadside assistance, training and safety equipment.

In Europe, the CoopCycle federation invites couriers, cooperatives and restaurants to use their open software to create worker-owned delivery platforms.

Couriers said customers also have a role to play, from being mindful about ratings and reviews, to tipping well and respecting realistic delivery times without calling and distracting drivers for an update.

But researchers say real change will come from regulations, policy changes and enforceable laws that protect the rights of workers.

"There is nothing inherently bad about platform work, it can be a positive thing," said Howson.

"But the way it is being manifested now is very exploitative." ($1 = 3.0900 laris) ($1 = 33.7500 baht)

RELATED STORIES

MULTIMEDIA - Life on the line: Deadly risks for world's food delivery drivers

Risks for South Africa's food couriers surge during the pandemic

EXCLUSIVE: Children in Brazil found working for food delivery apps

(Writing by Kim Harrisberg @KimHarrisberg; additional reporting by Annie Banerji in New Delhi, Umberto Bacchi in Tbilisi, Christine Murray in Mexico City, Nanchanok Wongsamuth in Bangkok, Avi Asher-Schapiro in Los Angeles, Anastasia Moloney in Bogota; Editing by Zoe Tabary. Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers the lives of people around the world who struggle to live freely or fairly. Visit http://news.trust.org)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.