* Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Thomson Reuters Foundation.

'Who owns what water?’ remains a controversial question for rural communities across the world. During World Water Week, we should be searching for answers.

This week is World Water Week in Stockholm, the annual focal point for the globe’s water issues. Several thousand experts are meeting to discuss water issues from sanitation to acute shortages facing particular regions. In this year’s meeting, water tenure is receiving slight mention. Yet ‘who owns what water?’ remains controversial for thousands of rural communities who regard local waters as integral to their historical and present domains, and continue to govern these under customary rules. This includes coastal communities who traditionally hold foreshores, mangroves, and near-shore fishing domains, and inland communities depending upon groundwater, ponds, lakes, small rivers, and marshes for their livelihood.

The status of inland local waters is sometimes contentious for various reasons, but two factors – water ownership and water use rights - are at the root of the problem

WATER OWNERSHIP

In countries around the world, national water legislation provides that inland water is either the property of the state or a public resource held in trust by (often undemocratic) governments for their citizens. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, resource laws in 44 of 49 countries (90 percent) stipulate that water is a state or public asset and the laws in three other countries imply this. Two-thirds of sub-Saharan countries do not recognize any private ownership of water. Yet a deeper look at these laws shows that many define a public asset as ownership by the national community in common, seeking a more equitable playing field (g. Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Lesotho, and Ivory Coast). However, in the process community rights may be jeopardized.

This African picture is reflected around the world; 57 of 67 water laws (85 percent) establish water as the property the state. Among the 10 water laws which do not make such claims, Aborigines in Australia and Sami in Finland and Norway are beneficiaries. In other cases a legal distinction is drawn between private and public waters sometimes with communities in mind. For example, in Nicaragua, communal property is legally defined as including waters traditionally belonging to the community.

A hint that the issue of water tenure is changing is indicated in the consistency with which new water laws are moving towards nationalized ownership. Again, Africa provides an example. Twenty-two of 26 (85 percent) water laws examined are not older than 1990, twelve enacted since 2000. Several older water laws provide more clearly for water to be attached to land rights (e.g. Botswana, Malawi, and The Gambia). It is also noticeable that national Constitutions in Africa are less strident than water laws in declaring all waters to be national, state or un-ownable property. In fact, only 13 of 55 Constitutions in force today do so. While many governments have focused on creating water user associations, few have adequately addressed community-level water tenure.

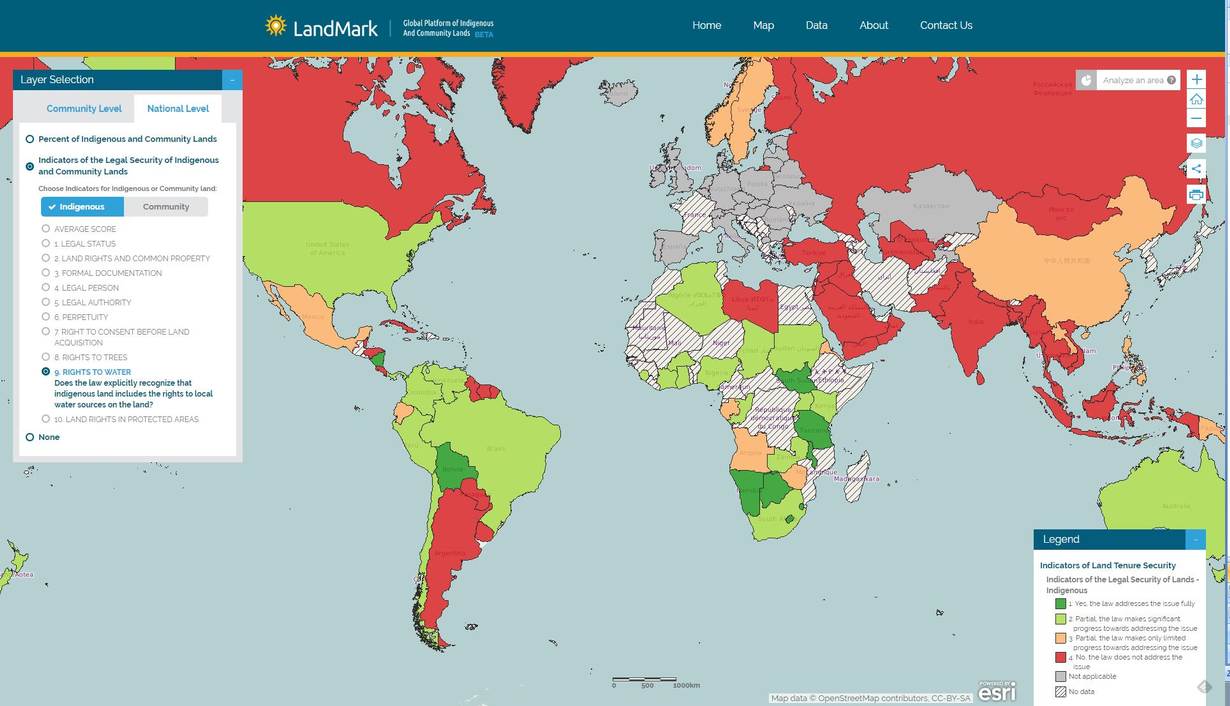

EXPLORE: discover the WRI's interactive map of water rights here.

Yet it is widely accepted that secure water tenure is a prerequisite to sound community management of local water resources. Laws in only 38 of 93 countries around the world (41 percent) explicitly recognize that indigenous and community property includes rights to local water sources on the land. Two thirds are African laws, suggesting African policy and lawmakers may be paying more attention to this issue than governments in other parts of the world. Elsewhere, the lands of Indigenous Peoples are often also beneficiaries. More generally, the link between secure local water tenure, land tenure, livelihood, and resource sustainability is still not being sufficiently made. No wonder many communities are worried. They may be gaining land rights but often waters on their land are excluded.

WATER USE RIGHTS

While water is predominantly a state or public resource, the laws in most countries around the world recognize and provide its citizens water use rights. In sub-Saharan Africa, the laws in half the countries recognize traditional or customary use rights to water. Most laws allow rural citizens and communities to use water for domestic or subsistence purposes without specific government authorization or payment of a fee. There are often, however, limitations, restrictions, or other conditions that apply to the exercise of these “free” water use rights with governments having the authority to revoke them for non-compliance.

Seventy-five percent of the world’s poor people live in rural areas, mostly in agrarian - land and natural resource dependent - economies. A better understanding of water ownership, water use rights, and how they link to land rights is fundamental to the livelihoods and welfare of 2-3 billion rural people. This in turn has connections to the stability of local resources themselves – and hence to climate change.

This year, the theme of World Water Week is Water for Sustainable Growth. Perhaps next year, attention can shift to water rights. The pro-poor orientation of the Sustainable Development Goals suggests we should be concerned.