The city is working to introduce green infrastructure, which can manage stormwater better, and create jobs into the bargain, says its resilience chief

By Megan Rowling

NEW ORLEANS, March 17 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - On a gray afternoon, a city worker tends plants on an undulating plot of grass known as a "rain garden". It's strategically placed on the corner of two streets in Gentilly, a quiet residential district in northeast New Orleans.

The garden can absorb up to 89,000 gallons of rainwater, which it then releases gradually into the city's drainage system, easing pressure on the network and reducing the risk of flooding.

It is one small example of the "green infrastructure" city authorities are planning much more of as part of New Orleans' effort to boost its ability to cope with extreme weather and other impacts of climate change.

"Water is our existential threat," Jeff Hebert, New Orleans' chief resilience officer, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation. His office in City Hall is just across the street from the Mercedes-Benz Superdome, where thousands of survivors sheltered in grim conditions after Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

That storm, which killed more than 1,800 people, wreaked most of its damage after levees meant to protect the city broke, unleashing water that flooded around 80 percent of the city.

"It was an infrastructure failure - and it's because we were heavily reliant on the gray infrastructure," said Hebert, explaining how the city famous for its jazz musicians has since moved away from depending simply on concrete walls and pumping stations to stay safe.

He attributes that change to the shock of Katrina - which displaced some 130,000 people, mostly from poor areas where some have never returned - and to a growing understanding of how the natural defences of the coastline, such as swamps, had been largely destroyed by a building boom since the 1950s.

"All those things started coming together after Katrina, and we knew we had to live a different way, and we had to start living with water again," said Hebert, who is also deputy mayor.

Learning anew how to work with the natural environment is not unique to Louisiana, he noted, but a growing trend in many parts of the world from China to the Netherlands.

RESILIENCE DISTRICT

One way to do it in places like New Orleans, which gets on average 60 inches (152.4 cm) of rainfall a year, is to find parts of the city that can absorb or hold excess water temporarily.

They could be vacant lots, green strips running down the middle or edges of streets, or rain gardens that can be created even in people's front yards.

This green infrastructure is already being put in place across the United States - but much more is needed "to be able to manage the rainfall that we have now and the precipitation we are going to see in the future", Hebert said.

To begin with, New Orleans is concentrating work of this kind in Gentilly, its first "resilience district", where it will make improvements to woodland, roads, parks and university campuses so they can help better manage stormwater.

The aim of the project - which won more than $141 million from the U.S. National Disaster Resilience Competition - is to reduce flood risk, slow land subsidence caused by intensive use of pumping systems, and encourage neighborhood revitalization.

One key feature will be the Mirabeau Water Garden located on 25 acres (10 hectares) of undeveloped land donated by the Sisters of Saint Joseph, whose convent on the site was destroyed by lightning after Katrina.

The plot will be able to store up to 10 million gallons of run-off water, while also acting as an "environmental classroom" to show the public how man-made filtration wetlands clean pollutants from water and improve its quality.

UNEVEN RECOVERY

While Gentilly is not among the poorest neighborhoods, Hebert said a large part of the city's wider strategy to build resilience in coming years will focus on making New Orleans a more equitable place.

The strategy, released in August 2015 - one of the first among 100 cities worldwide participating in a Rockefeller Foundation program to boost their resilience - notes that New Orleans' "remarkable" recovery and growth in recent years has not benefited all sections of society.

One key focus of the "Resilient New Orleans" strategy is to provide training for jobs in the green economy and water management - whether in construction, pipe-fitting or landscaping, Hebert said.

"We have moved people from jobless and under-employed to jobs that are... connected to the future economy," he said.

In New Orleans, there is a direct correlation between lower-income areas, which tend to have high percentages of people of color, and climate vulnerability. Many poor neighborhoods tend to be the most exposed to flood threats, Hebert added.

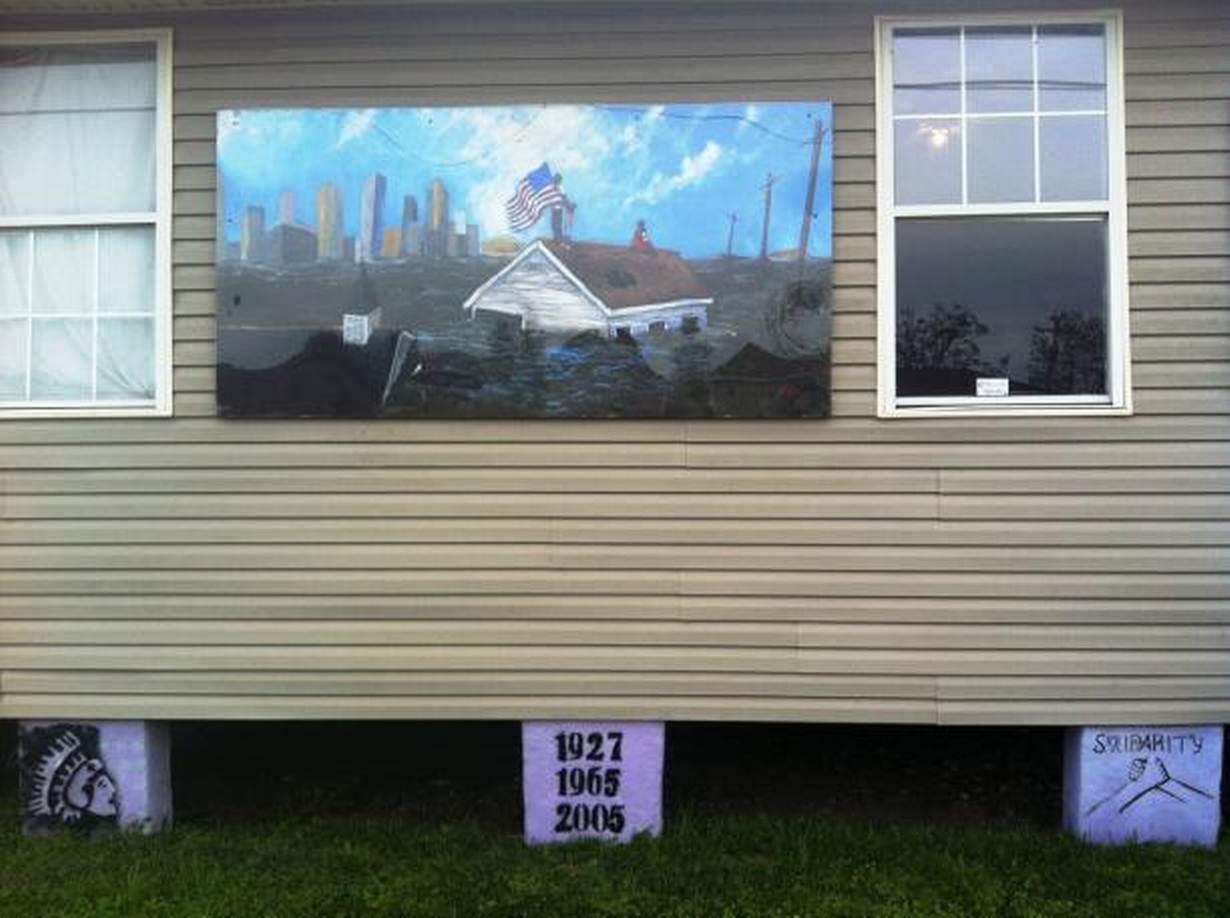

In the Lower Ninth Ward, for example, which bore the brunt of flooding after Katrina, with people having to be rescued from their rooftops, only one in three residents have returned and poverty levels remain high.

Raising awareness of the risks neighborhoods like these face - and how their inhabitants could access support to protect themselves and their homes - is another pillar of the resilience strategy, Hebert said.

The city also plans this spring to announce targets for reducing its greenhouse gas emissions and set out the actions it will take to achieve those.

The main challenge in turning resilience from a goal to a reality, Hebert said, is keeping the need for it at the forefront of people's minds - using events such as February's freak tornadoes in Louisiana to remind them.

"You don't need another Katrina," he added. Any weather extreme is a chance to "re-emphasise why taking certain actions is important".

(Reporting by Megan Rowling @meganrowling; editing by Laurie Goering. Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers humanitarian news, climate change, resilience, women's rights, trafficking and property rights. Visit http://news.trust.org/climate)

The Thomson Reuters Foundation is reporting on resilience as part of its work on zilient.org, an online platform building a global network of people interested in resilience, in partnership with the Rockefeller Foundation.

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.