* Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Agriculture is more efficient than ever, food is more abundant and cheaper, yet its ability to nourish people has declined

Professor Tim Benton is Co-Chair of the Lead Expert Group developing and drafting the Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition’s second Foresight report. He is also Distinguished Visiting Fellow in the Energy, Environment and Resources Department at Chatham House, and Dean of Strategic Research Initiatives at the University of Leeds.

Today, global agriculture is more efficient than ever. Between the 1960s and 2005, global agricultural output rose enormously. Whilst the global population rose 2.1 times, calorie production rose 2.7 times,with cereal production increasing from 843Mt to 2068Mt, and meat production increased from 72Mt to 258Mt. In 1961 there were 7.1bn livestock, in 2014 there were 28.2bn (mainly through increases in chickens).

Over the same time period, the World Bank food price index trended downwards, declining by 37% in real terms. As the US Department of Agriculture says, “Over the past 50 years, productivity growth in agriculture has allowed food to become more abundant and cheaper”. Yet at the heart of this remarkable achievement lies a real paradox: as the availability of food has become greater, its ability to nourish the world’s population has declined.

The reason for this is, at least at one level, simple.

We have built a food system that integrates the global with the local, so each country’s food depends, to a greater or lesser extent, on food produced locally and food produced globally. Through incentivising productivity growth – such as through research and technology, producer subsidies, regulations or infrastructure – and liberalising global trade, we have a globally competitive market that rewards countries with comparative advantage to produce at scale. A small handful of crops, those that can be grown at scale in bread-basket regions, have come to dominate the world’s markets – wheat, rice and maize contribute 50% of the world’s calories, and a further 5 crops, barley, potatoes, soya, sugar and palm oil, contribute another 25%.

These crops dominate the world’s markets for a couple of reasons. Firstly, they can be stored, transported and processed easily (unlike, for example, lettuce). Secondly, they provide generic ingredients: starch, oil, sweetness, protein, that can form the basis of a huge array of processed foods. One only has to walk through a supermarket looking at food labels to see how ubiquitous they are in food items on shelves.

Thirdly, the sheer scale of the commodity markets incentivises growing these crops, and so, in many parts of the world, traditional crops have given way to these commodities.

The scale of production is driven by pragmatism, and economics. As these crops have taken over the world, everyone’s diets have increasingly become underpinned by this same small handful of crops, so whilst the exact foods might differ from Algeria to Zimbabwe, increasingly people eat foods made from the same ingredients.

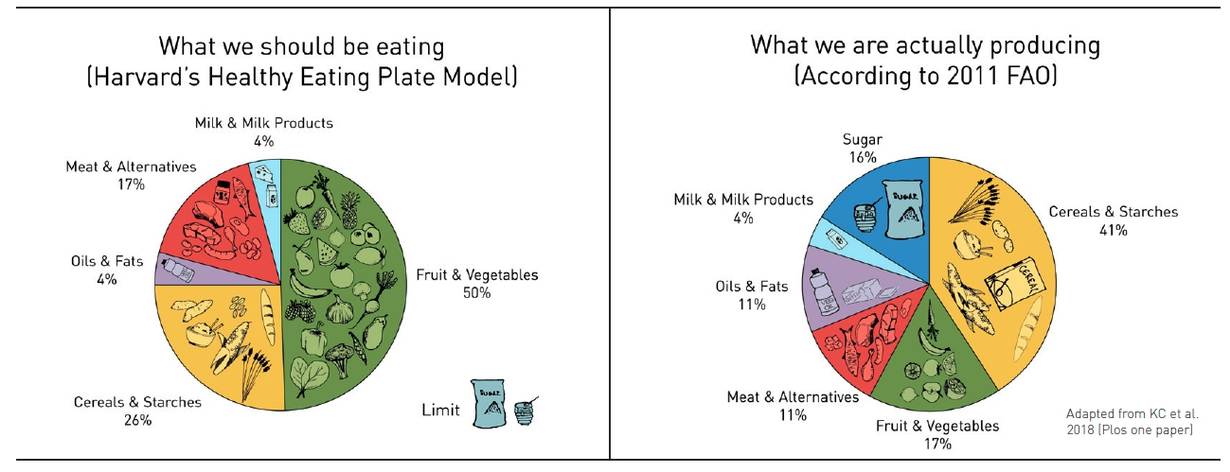

That would be all right but for two enormous constraints. Firstly, the “big 8” crops do not underpin diets that are nutritious, promoting good dietary health. If we compare the sorts of mixes of food that people should, on average, eat, we get a “plate” – estimated from the number of servings recommended by dietary guidelines - similar to the one on the left. In other words, this is a guideline based on proportion weighted by recommended serving size for the foods in question, noting that a serving of cheese (~50g) is different in weight, calories and nutrient profile from a serving of lettuce (1.5 cups, ~90g).

In contrast, the economics of food system produces food in the proportions on the right. On the one hand, agriculture produces far more sugar than recommended for health, about 60% more grains, and nearly 3 times too much oil and fat; and on the other, it produces about two-thirds the amount of protein-rich food, and only a third the amount of fruit and vegetables. What the world grows, and what people need for healthy diets, are quite different.

Second, concentrating on growing more of fewer crops has reduced the price and increased the availability of calorie-rich food. This incentivises over-consumption for many, and further wasting food becomes economically rational.

The sustainable intensification of agriculture will not fix these issues. We need to design a food system that puts people and planetary health front and centre. I am co-chair of the expert group leading on the elaboration of a second Global Panel Foresight report on future diets. This new evidence will provide vital information for the Global Panel and its partners to sensitise policymakers on the urgent need for food systems to deliver healthier diets and better nutrition for the future.