As floods batter the north and dry weather parches the south, scientists warn there is more to come if Brazil does not tackle deforestation

* Shifting weather patterns have already hit power grid and farms

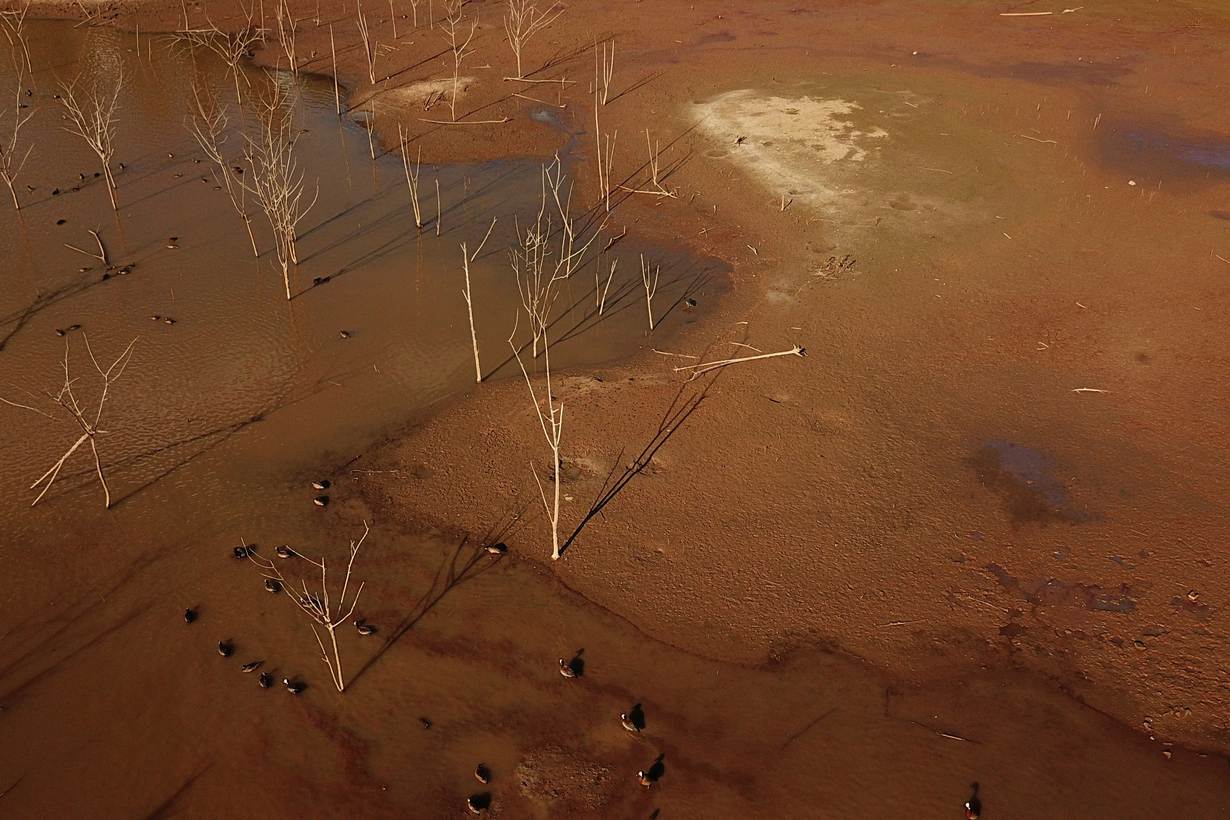

* Parts of Brazil are seeing the worst flooding in a century

* Tree loss in Brazil's Amazon rose 17% in first half of the year

By Fabio Zuker

SAO PAULO, Sept 21 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - In May and June, heavy rain pushed Brazil's sprawling Negro river to its highest level in more than a century, causing flooding in Manaus, the Amazon rainforest's largest city.

At the same time, parts of southern and west-central Brazil in the Paraná River basin - including Brazil's largest city of Sao Paulo - have suffered unprecedented drought due to low rainfall.

The disastrous mix of floods, drought and intense downpours could be a glimpse of a potentially dire future as a heating planet and surging deforestation alter long-standing weather patterns throughout Brazil and South America, scientists warn.

Climate shifts could lead to a range of environmental and socioeconomic shocks, from dwindling farm harvests to more destructive forest fires and energy blackouts, climate and forestry experts told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

"What we see now in terms of extremes in temperature and rainfall are perhaps a sample of things that may come if warming continues," said José Marengo, a climatologist with Cemaden, the Brazilian government's disaster monitoring center.

Climate experts say deforestation of the Amazon and the Cerrado - the largest savanna in South America - are key drivers of the country's changing climate patterns.

"The process (of climate change) is becoming stronger because of human activities," Marengo said.

In the first six months of this year, the amount of forest cleared in the Brazilian Amazon rose 17% compared to last year, with 3,600 square kilometers (1,400 square miles) disappearing, according to national space research agency Inpe.

Most of the tree losses were to make way for soy farming and cattle rearing, as Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro focuses on expanding agribusiness as the development model to boost the Amazon region's economy.

FLOODS AND FIRES

Increasingly heavy rain and floods in the Amazon are linked to atmospheric changes caused in part by ocean warming linked to climate change, said Jochen Schoengart, a researcher with the National Institute for Amazonian Research.

During the first 70 years of water level measurements at the port in Manaus, a big flood was recorded every 20 years, said Schoengart, who specializes in the history of hydrological cycles and forest floods.

But "in the last 10 years, we have seen seven major floods. And among those big seven, we have the two biggest on record, in 2012 and now in 2021," he said.

In other biomes south and east of the Amazon, changing climate patterns are having the opposite effect, with areas gasping for water as abnormal cooling of the Pacific - a weather anomaly known as La Nina - contributes to unusually dry weather.

Hydropower reservoirs the country heavily relies on have become severely depleted, prompting the government to ramp up its use of polluting fossil fuels. The country warned in May it faced its worst dry spell in 91 years this year.

In its latest annual report, the Ministry of Mines and Energy said more than 65% of the country's electricity comes from hydropower, with the rest mainly generated by biomass-fueled power plants and wind turbines.

Harsher drought is also making forest fires worse, scientists said, pointing to severe blazes in the Pantanal wetlands and along the Paraná River over the past two years.

Figures from the Life Center Institute, a Brazilian nongovernmental organization focused on biodiversity preservation, show from January to mid-November 2020 fires consumed 8.5 million hectares (21 million acres) in Mato Grosso - about 10% of the central Brazilian state's total area.

That represented a 54% rise in fire "hotspots" in 2020 compared to the previous year, the group said.

FARM LOSSES

Besides the threat of power shortages and more destructive forest fires, climate experts say the drier weather is also causing agricultural losses.

A study published in May in the journal Nature Communications estimated that agribusiness is losing up to $1 billion a year as rising deforestation cuts rainfall in parts of the country.

Marengo said the problem stems in part from disruption of a weather phenomenon climatologists call "flying rivers".

These are large quantities of humid air that move over the Amazon from the Atlantic Ocean, along the way picking up water vapour evaporating from trees and later releasing it as rainfall, he said.

When the air currents hit the natural barrier of the Andes mountains, they shift south, where they meet a cold front and turn into what used to be regular, abundant rains, scientists say.

But with fewer forests to help trigger rain showers along the way, the flying rivers have become faster and more concentrated, Marengo explained.

When they reach more southerly areas of Brazil they release short, intense rainstorms - like a runaway train ejecting all of its passengers at once, he said.

The result is often increasingly deadly flash floods and mudslides like those that hit the states of Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo last year, he added.

In Brazil's farming areas, when rain does come, it arrives less often and can be very heavy, making it harder to provide the consistent moisture crops need, farmers say.

"It is raining half of what it used to, and very, very concentrated storms," said Alexandre Barretto, a soybean and cattle farmer in the city of Juscimeira, in Mato Grosso state.

Last year, Barretto's farm got an average of 1,200 millimeters (47 inches) of rain, half the historical annual average, noted the farmer, who lost about 15% of his soybean crops.

"It is a general worry among farmers. The time frame for planting has become just too short," he said in a video call.

Preliminary data published by Inpe in September gave a hint of hope to those calling to save the Amazon, with figures showing tree loss in the forest region falling for a second consecutive month in August, dropping 32% compared to a year ago.

But deforestation remains nearly double what it was in the first eight months of 2018, prior to Bolsonaro taking office.

For Marengo, the solution to Brazil's worrying rainfall changes is to keep pushing the government to halt, and then reverse, the destruction of the Amazon.

"The forests are extremely important," he said. "We have to reduce deforestation, we have to plant more trees. Otherwise, we will have consequences."

Related stories:

More deforestation - and less rain - threaten Brazilian agribusiness

Amazon losses help drive growing wildfires elsewhere in Brazil

Spotlight: Amazon forest and climate change

(Reporting by Fabio Zuker; editing by Jumana Farouky and Laurie Goering. Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers the lives of people around the world who struggle to live freely or fairly. Visit http://news.trust.org/climate)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.